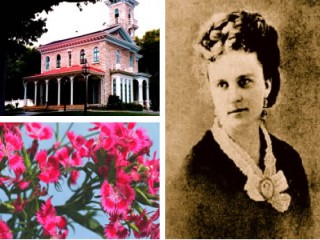

Kate Chopin biography

Date of birth : 1851-02-08

Date of death : 1904-08-22

Birthplace : St. Louis, Missouri, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-10-04

Credited as : Writer and translator, tales by de Maupassant, The Awakening

1 votes so far

Kate Chopin is considered among the most important women in nineteenth-century American fiction. She is best known for her 1899 novel, The Awakening, a once-scandalous account of one woman's growing sexuality in the American South during the Victorian era. For this novel, Chopin faced critical abuse and public denunciation as an immoralist, and she consequently abandoned writing. In more recent years, however, The Awakening has grown in stature and is now recognized as a masterpiece of its time. Critics such as Van Wyck Brooks and Edmund Wilson have commended the novel, and numerous others, including Cynthia Griffin Wolff, Anne Goodwyn Jones, and Elaine Gardiner, have subsequently revealed its social and psychological themes. The efforts of these and other critics have helped establish Chopin as a significant figure in American, particularly feminist, literature.

Chopin was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1851. Her mother, Eliza Faris O'Flaherty, was a member of the prominent French-Creole community and was thus a familiar figure in exclusive social circles. Chopin's father, Thomas O'Flaherty, was an Irish immigrant who had successfully established himself as a merchant and subsequently participated in various business ventures. Chopin was only a child when her father died. He had been a founder of the Pacific Railroad, and he was aboard the train on its inaugural journey when it plunged into the Gasconade River after a bridge collapsed.

After the train disaster, Chopin established a more intimate relationship with her mother, who had grown increasingly religious. Chopin also developed a strong tie to her great-grandmother, who guided her studies at the piano and in French and offered moral counseling. The older woman also regaled young Chopin with tales of French settlers from St. Louis's past. Among these stories, however, were accounts of notorious infidels, and more than one scholar has suggested that these tales made a vivid impression on Chopin.

During her school years Chopin read voraciously, showing an appetite for fairy tales, religious allegory, poetry, and novelists ranging from Walter Scott to Charles Dickens. Around age eleven, Chopin endured further heartache when her great-grandmother died. Soon afterwards, Chopin's half-brother, who had been captured as a Confederate soldier in the Civil War, contracted typhoid fever and died. These losses compelled Chopin to delve more intensely into literature, and for the next two years she secluded herself in the family attic--even missing school--and studied more books. When she resumed her formal studies at a Catholic school, Chopin worked diligently, though without great scholastic distinction. She did, however, gain repute as a proficient and creative storyteller.

Chopin graduated from the Catholic school in 1868, and for the next two years she enjoyed life as a belle in St. Louis's high society, earning admiration for both her beauty and her wit. She continued to read extensively, but her interests were not limited to the classics, and she showed familiarity with the works of many contemporary writers. In addition, Chopin devoted herself to music--practicing the piano and patronizing the city's symphony and its opera companies.

An Independent Woman

But as she reveled in St. Louis society, Chopin became increasingly independent. She began questioning Catholicism's implicit authoritarianism, which dictated subservience for women to male domination, and she showed heightened awareness of the inanities involved in socializing. In the spring of 1869, Chopin traveled to New Orleans and befriended a charismatic, independent--though married--German singer and actress. Chopin was impressed with the woman, who seemed to maintain her individuality despite marriage. After returning to St. Louis, Chopin made another acquaintance, Louisiana native Oscar Chopin, who had arrived in the city to work in a bank. A year later the two were married.

The Chopins honeymooned in Europe, where they visited renowned cities and attended plays and musical performances. Their travels, though, were abbreviated by commencement of the Franco-Prussian War, and they returned briefly to St. Louis before establishing themselves in New Orleans. Although Oscar Chopin was French-Creole, the couple settled in the city's American district, thereby incurring the wrath of Oscar's father, who owned plantations in northern Louisiana and expected his son to maintain his Creole ties and perhaps even join him in operating the properties. But Oscar's father was a tyrant who had been known to violently abuse both his slaves and his son. Oscar, therefore, opted for a less troubling career as a cotton factor and began handling sales, finances, and supplies for other plantation owners.

While her husband worked, Kate Chopin continued her relatively iconoclastic life. She pursued her interest in the performing arts, developing a preference for the operas of Richard Wagner, and she persisted in her habit, then considered highly unusual for women, of smoking cigarettes. Chopin also became familiar with her surroundings by adopting another habit, also unusual for young women, of walking unaccompanied through the city.

While walking alone through New Orleans, Chopin witnessed organized terrorism against blacks. Moreover, Oscar Chopin was a member of the White League, which clashed violently with Republicans sympathetic to blacks--one conflict claimed forty lives. Racial confrontations, however, were not the only cause for concern in New Orleans. Yellow fever was also spreading rampantly, killing four thousand citizens in 1878 alone. Per Seyersted, author of the critical biography Kate Chopin, speculates that Chopin--who had six children, including five sons, by 1879--may have been motivated by health considerations in making several trips to St. Louis with her offspring.

Also by 1879 Oscar Chopin's factoring business had collapsed, whereupon the family moved north to the family plantations in Natchitoches Parish. There the Chopins became active members of the revived Creole community, and Kate Chopin won admiration for her convivial nature and superior intellect. But Oscar Chopin, whose health seemed consistently weak, contracted swamp fever during the winter, and, in January, 1883, he died. Kate Chopin remained in Natchitoches Parish for nearly one year and continued operating the plantations, but with little success. In 1884, she finally acceded to her mother's frequent requests to move with the children to St. Louis. The next year, Chopin's mother also died. In her critical volume Kate Chopin, Peggy Skaggs observes that Chopin's self-perception must have been affected by the various family deaths, and that the consequent tension may have resulted in the "search for self-understanding" that motivates so many characters in Chopin's fiction. Following her husband's death, Chopin was consoled by the family physician, Frederick Kolbenheyer. With Kolbenheyer's encouragement, Chopin began writing about the Louisiana of her past. Her efforts resulted in "If It Might Be," a poem that Seyersted suggests may express Chopin's desire to join her late husband in death. "If It Might Be" appeared in the Chicago periodical America in early 1889, thus affording Chopin the rare luxury of publishing her first submitted work. But she then encountered technical difficulties in writing a pair of short stories, and only after reading a small collection of French writer Guy de Maupassant's tales did Chopin believe herself capable of producing fiction. After this realization, Chopin published the short stories "Wiser Than a God," which concerns a pianist who forsakes marriage for a music career, and "A Point at Issue," which chronicles the decline of an emancipated marriage into a conventionally restrictive, male-dominated union.

A Determined Writer

Chopin next produced a novel, At Fault, about morally complex--and unintentionally preposterous--romantic considerations. In this novel, a young widow, Therese, discovers that a prospective second husband, the Creole David Hosmer, had divorced his first wife after learning that she was an alcoholic. Therese's moral absolutism prompts her, despite her love for David, to promote his re-marriage to his ex-wife. Incredibly, he heeds her counseling and rejoins his former spouse, who eventually succumbs once more to alcoholism. Therese and David seem fated for more suffering until the alcoholic accidentally, but conveniently, drowns, thus allowing the lovers to unite without moral compromise.

At Fault addressed many of the themes, including women's emancipation and marital discord, that Chopin rendered more subtly in subsequent works. Upon its publication in 1890, the novel earned mixed reviews for its daring portrayal of a female alcoholic and its ambivalent perspective on divorce. Chopin had assumed financial responsibility for the book's publication and had sent copies to leading magazines and newspapers, including the local St. Louis Post-Dispatch, whose critic complained of At Fault's allegedly immoral tenor but praised Chopin's skill in avoiding a moralistic tone. Similarly, a Nation reviewer noted that the novel's plethora of characters--in sub-plots involving arson and violence--all shared a lack of admirable traits. But the Nation reviewer added that Chopin possessed an "aptitude for seizing dialects of whites and blacks alike" and commended her "skill in perceiving and defining character."

Chopin followed At Fault with another novel, Young Dr. Gosse, for which she was unable to procure a publisher. Undaunted, she returned to writing shorter works, and in the next few years she produced more than three dozen stories and sketches. Chopin first found steady publication in children's magazines such as Youth's Companion and Harper's Young People. In 1893, she appealed to adult readers with two tales in Vogue. These stories apparently proved popular, for in the next seven years the magazine published an additional sixteen pieces by Chopin.

Chopin collected twenty-three of these stories and brief sketches and published them in 1894 as Bayou Folk. In this collection, Chopin established herself--at least to her contemporaries--as primarily a masterful colorist of Louisiana life. An Atlantic Monthly reviewer, for instance, cited Chopin's reproductions of Southern speech and lauded the simplicity and concision of the tales, while a writer for the Critic praised Chopin for her sincere, simple portraits of bayou life. The Critic's reader also called Bayou Folk an "unpretentious, unheralded little book" and commended Chopin's "shrewdness of observation and. . . fine eye for picturesque situations."

But Bayou Folk, despite the contentions of its initial readers, transcends mere portraiture in addressing such controversial subjects as infidelity and racial purity. Among the most famous tales in this collection is "Desiree's Baby," in which a woman disappears into the Louisiana bayou with her baby after her husband, distressed by the infant's features, accuses the woman of possessing Negro blood. This story offers chilling commentary on human behavior and fate, for no sooner has his wife vanished than the husband discovers that he is the parent with black ancestry. In another famous tale, "A Lady of Bayou St. John," a naive young wife falls in love with a visiting Frenchman while her husband is fighting in the Civil War. Before fleeing to Paris with her new love, the woman learns of her husband's death, whereupon she rejects the Frenchman and pledges herself to the dead man's memory. In this and other tales, Chopin proved herself an artist of great insight into human behavior. Her work's complexity, however, eluded critics until long after her death.

Although reviews of Bayou Folk were superficial and relatively unperceptive, they were nonetheless favorable and afforded Chopin sufficient motivation to continue writing. She still circulated her novel Young Dr. Gosse, but the manuscript met with further rejection, and, in 1896, she finally destroyed it. She found greater acceptance for her shorter fiction, and, by 1897, she had completed enough to form another collection, A Night in Acadie. This volume marked Chopin's growing interest in sexuality, passion, and the stasis of conventional marriage. Among the many acclaimed stories in this collection is "A Sentimental Soul," in which a devout, unmarried woman, Mamzelle Fleurette, falls in love with a married man. She confesses her feelings to a priest, who unsympathetically counsels discipline. After the married man dies from fever, the woman continues to love, but the priest warns her not to attend the funeral. Finally, Fleurette consults another priest, to whom she confesses only insignificant sins and not her profane love. Walking home afterwards, Fleurette experiences an exhilaration as she realizes that she must henceforth hold herself in confidence. A Night in Acadie also includes the celebrated tale "Athenaise," where a young bride twice flees her husband due to her diminished sense of self, and "A Respectable Woman," in which a wife represses her passion for her husband's friend. The best of A Night in Acadie thus indicates Chopin's increased concern for the plight of women in Victorian-era America.

Chopin produced the stories in A Night in Acadie despite a seemingly disadvantageous regimen. She wrote only one or two days each week, and even then she only wrote in her living room amid her playing children. With so little time for writing, Chopin considered most tales to be complete after an initial draft, which Chopin would then submit for publication. Aside from her strictly literary pursuits, Chopin presided over a modest salon that hosted prominent St. Louis intellectuals and celebrities. They convened at her home on Thursdays and debated timely philosophical and literary subjects. In addition, Chopin had been a member of the Wednesday Club, a women's organization co-founded by poet T. S. Eliot's mother devoted to both social and cultural issues. Chopin resigned from this group after two years due to dissatisfaction with the club's ideals and pretensions, reports biographer Per Seyersted in Kate Chopin.

When A Night in Acadie appeared in 1894, it too received critical praise for its convincing portraits of Louisiana life. Although it was not reviewed as extensively as was Bayou Folk, it nonetheless confirmed Chopin's reputation as an adept colorist. A reviewer in Nation, for instance, declared that Chopin "reproduces the spirit of a landscape like a painter," and the writer noted Chopin's skill in "seizing the heart of her people and showing the traits that come from their surroundings." Likewise, a Critic reviewer cited Chopin's ability to write about "the simple, childlike southern people who are the subjects of her brief romances."

By the time A Night in Acadie appeared Chopin was already preparing a third collection, A Vocation and a Voice. But this volume, which included tales previously rejected by magazines, was declined by publishers uncomfortable with Chopin's increasingly radical perspective on love, sex, and marriage. In some tales, she equated sexual passion with religious devotion, and in others she explored the power of passion. Chopin also explicitly denounced conventional marriage and its restrictive role for women. In this collection's most popular work, the often-anthologized "Story of an Hour," a semi-invalid learns of her husband's death and begins anticipating her newfound independence. Like "Desiree's Baby," however, this story ends in sudden, pessimistic fashion when the wife discovers that her husband is actually alive. She then dies of heart disease.

Chopin's Masterpiece

Chopin was undeterred by the rejection of her third collection and continued writing at an impressive pace. Aside from her short stories, she produced dozens of poems, translated several tales by de Maupassant, and contributed critical essays to various St. Louis periodicals. Fiction, however, was Chopin's greatest strength, and even as she vainly submitted A Vocation and a Voice for publication she was writing a second novel, The Awakening. This work, which would eventually be recognized as her masterpiece and a seminal work in American feminist fiction, first proved her most notorious publication and her literary undoing.

Like much of Chopin's fiction, The Awakening is about a dissatisfied wife in Louisiana. The protagonist, Edna Pontellier, is a reserved, sensitive young woman who first appears in the novel while vacationing at a summer resort with her children. On weekends she is met by her husband, a New Orleans broker. Otherwise she has only a few adult companions, including a young Creole named Robert Lebrun. Edna first responds cordially to Robert's constant attention. Early in the novel, however, she gains a greater sense of boredom with her life and becomes increasingly aware of passionate feelings for her male friend. But at dinner one evening, Edna is stunned to discover that Robert has hastily arranged his departure for Mexico, an arrangement doubtless intended to abbreviate their romance. Edna is consequently unnerved, but she understands that her life has been irrevocably changed: she has been awakened to her thoughts, her feelings, her potential.

After she and her family have returned to New Orleans, Edna begins neglecting her duties as wife and mother. She abandons housekeeping, refuses guests, denies her husband his conjugal privilege, and eventually moves from their home to a nearby cottage. With his life drastically disrupted, Edna's husband strives to maintain his social stature. Edna understands that, in his own way, her husband actually loves her, but she also knows that his own way involves perceiving her more as property than as a separate human entity with thoughts and feelings.

Edna eventually adopts a fairly Bohemian existence--painting and circulating among musicians and others who accept her independence. She also enters into a sexual relationship with a notorious philanderer, but she longs for Robert. Edna does not find fulfillment in her new life, however. Her art work is only mediocre, and her love affair is only satisfactory sexually. When Robert returns from Mexico, she seduces him and declares her devotion. While revelling in her love and her freedom, however, she is rushed away to assist a friend giving birth. When Edna returns home, she discovers that Robert has once again fled from her affection. "Good-by--because I love you," is all he has written as a farewell note. Despondent at her lover's desertion and her friend's anguished birthing experience, Edna returns to the seaside resort where she had first fallen in love with Robert. There she disrobes and drowns herself.

Critics React Strongly

The Awakening was received with indignation when it appeared in 1899. Critics claimed that Chopin was a pornographer and that her novel was immoral and even perverse. Among her many detractors was a reviewer for Public Opinion, who was "well satisfied" by Edna's suicide, and a critic for Nation, who noted the "unpleasantness" of reading about the allegedly headstrong protagonist. Willa Cather was also among the legion of readers who denounced The Awakening, complaining that Chopin had wasted herself on a "trite and sordid" theme. Of course, Chopin's novel was not entirely without its supporters. A critic for the New York Times Book Review, for example, noted Chopin's skill in exploring her subject and confessed "pity for the most unfortunate of her sex." But reviews such as this were rare in the overwhelmingly negative dismissal of the novel.

Chopin was understandably despondent over the reception accorded The Awakening. This public condemnation, coupled with the continued rejection of A Vocation and a Voice, is believed to have precipitated the end of her literary career. Contrary to popular belief, however, Chopin did not immediately cease writing in the wake of continued abuse. In the next year, she wrote several stories, including "The Storm," which anticipated the work of English writer D. H. Lawrence with its frank depiction of two lovers' infidelity during a thunderstorm. Gradually, then, Chopin abandoned her career. By 1904 her health was also in decline. Fascinated, however, by the World's Fair in St. Louis, Chopin made daily excursions. After a particularly exhausting day, she collapsed with a cerebral hemorrhage. Two days later, on August 22, she died.

In the ensuing years Chopin's notoriety for The Awakening faded, and her literary reputation became dependent on critics who considered her essentially a colorist. For many years it was thus commonly held that Chopin was foremost a re-creator of Louisiana life, particularly that of the bayou. But by the 1930's critical opinion began to change. Daniel S. Rankin, in his important study Kate Chopin and Her Creole Stories, hailed her as a masterful realist, and Shields Mcllwaine wrote in The Southern Poor-White that Chopin was gifted at expressing "the emotional values" of her characters. By 1952, literary historian Van Wyck Brooks had even acknowledged The Awakening as an undeservedly slighted work. He called the book "one novel of the nineties in the South that should have been remembered, one small perfect book that mattered more than the whole life of many a prolific writer," and he commended the novel for its "naturalness and grace." Critics such as Robert Cantwell and Kenneth Eble followed Brooks's comments in the mid-1950s by hailing The Awakening as profound as well as evocative. Cantwell, writing in the Georgia Review, praised Chopin's "heightened sensuous awareness" and deemed The Awakening "a great novel," while Eble wrote in Western Humanities Review that Chopin was superb at characterization and that she had created a "first-rate novel." And in his 1962 volume Patriotic Gore, noted literary authority Edmund Wilson commended The Awakening as "quite uninhibited and beautifully written."

In more recent years Chopin and her work have become favored subjects among women critics. Priscilla Allen, in an essay included in the volume Authority of Experience, charged that the preponderance of male criticism had even served to distort the characterization of The Awakening's Edna Pontellier and ignored her role as a representative of the oppressed. Taking a more sociological approach was Anne Goodwyn Jones, who wrote in Tomorrow Is Another Day that the plight of women in Chopin's fiction is not unlike that of black slaves. In her book, Jones analyzed Chopin's perception of sexual repression and its effect on both individuals and their society. Still other women, including Cynthia Griffin Wolff in "Thanatos and Eros," an article for American Quarterly, contested these sociological interpretations of Chopin's work and argued for a more psychological approach, while critics such as Carol P. Christ, who wrote of women writers in Diving Deep and Surfacing, viewed Chopin's writing in largely spiritual terms.

But Chopin's work is not exclusively a subject of study for American women. It has exerted appeal in countries ranging from France to Japan. Indeed, the world's foremost authority on Chopin and her work is probably Per Seyersted, a Norwegian male. Thus Chopin's work, like that of any great writer, transcends specifics of time and place and holds relevance for readers regardless of gender or nationality.

1890: At Fault (novel), Nixon-Jones Printing Co..

1894: Bayou Folk (short stories), Houghton, reprinted, Gregg Press, 1967, reprinted with introduction by Warner Berthoff, Garrett Press, 1970.

1897: A Night in Acadie (short stories), Way & Williams, reprinted, Garrett Press, 1968.

1899: The Awakening (novel), Herbert S. Stone, reprinted with introduction by Kenneth Eble, Capricorn, 1964, reprinted with introduction by Warner Berthoff, Garrett Press, 1970, reprinted in critical edition edited by Margaret Culley, Norton, 1976.

Contributor of articles, short stories, and translations to periodicals, including Atlantic Monthly, Criterion, Harper's Young People, St. Louis Dispatch, and Vogue. Also author of unpublished novel Young Dr. Gosse. Work represented in numerous anthologies.

Collections

1969: The Complete Works of Kate Chopin (two volumes), edited by Per Seyersted, Louisiana State University Press.

1970: Kate Chopin: The Awakening and Other Stories, edited by Lewis Leary, Holt.

1974: The Storm and Other Stories, with The Awakening (includes "Wiser Than a God," "A Point at Issue," and "The Story of an Hour"), edited by Per Seyersted, Feminist Press.

1976: The Awakening and Selected Short Stories of Kate Chopin, edited by Barbara Solomon, Signet.

1979: A Kate Chopin Miscellany, edited by Per Seyersted, Northwestern State University Press.

1991: A Vocation and A Voice: Stories, Viking.

1992: Matter of Prejudice & Other Stories, Bantam.

1993: Kate Chopin, "The Awakening": Complete, Authoritative Text with Biographical & Historical Contexts, Critical History, and Essays from Five Contemporary Critical Perspectives, edited by Nancy A. Walker, St. Martin's.

1993: The Awakening and Selected Stories, edited and with introduction by Nina Baym, Modern Library (New York City).

1996: A Pair of Silk Stockings and Other Stories, Dover Publications (Mineola, NY).