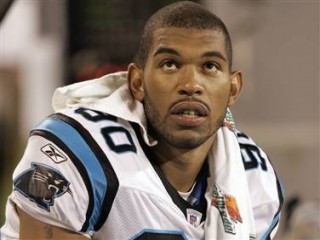

Julius Peppers biography

Date of birth : 1980-01-18

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Wilson, North Carolina, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-23

Credited as : Football player NFL, currently plays for the Carolina Panthers, Super Bowl

2 votes so far

Julius Frazier Peppers was born on January 18, 1980 in Wilson, North Carolina. His parents, Bessie (who also goes by “Faye”) Peppers and George Kurney met in 1979. The two entered into a relationship that cooled after Julius arrived.

A disinterested parent, George gradually faded from the picture. By his son’s seventh birthday, he had almost completely disappeared. One reminder of him was Julius’s long, powerful frame. George had been quite an athlete in his day, and Julius showed signs of developing similar speed, strength and coordination.

George made one other significant contribution to Julius's life. A huge basketball fan, he named his son after his two favorite players, Julius Erving and Walt Frazier.

The responsibility of raising Julius fell to Bessie. She also looked after another son, Stephone, the product of her marriage to Clarence Peppers (which ended in divorce in 1978). Bessie was loving, but strict. She demanded that her boys treat her and others with respect. For Julius, these lessons carried onto the athletic fields.

The Peppers eventually settled in Bailey, a one-diner town (pop: 690) located some 30 miles east of Chapel Hill. Not surprisingly, Julius grew to love basketball. Known as Big Head because of his large cranium, he dreamed of being the next Michael Jordan. The youngster liked nothing more than shooting baskets by himself. Sometimes he played Stephone one-on-one, but the solitude offered by a vacant court was nirvana for him.

As he got older, Julius matured into an amazing physical specimen. He stood 6-5 and weighed 225 pounds at the start his freshman year at Southern Nash Senior High School. Basketball, which Julius saw as his ticket to fame and fortune, remained his primary passion.

Southern Nash football coach Ray Davis had a different idea. After one look at the strapping teenager, he became intent on getting Julius in pads and a helmet for the Firebirds. The frosh, however, had never played football, and wasn’t all that enamored of the thought of banging bodies with the upper classmen. Davis convinced him otherwise by promising to make him a running back.

As Davis suspected, Julius was a terror on the gridiron. For his career, he rushed for 3,501 yards and 46 touchdowns. He made an even greater impact on defense. Davis installed him on the defensive line and let him loose on opposing quarterbacks and running backs. Though most teams ran their offense away from him, Julius still found ways to dominate games. In the final contest of his career, he tracked down a back for Northeast Guilford High School, stripped the ball and raced 90 yards for a touchdown.

Though Julius also starred as a triple jumper and sprinter in track, he still felt his future was brightest in hoops. A power forward with a nose for the ball and outstanding leaping ability, he earned All-State honors as a senior and was voted All-Conference four times. In four years with Southern Nash, he amassed more than 1,600 points, 800 rebounds and 200 assists. During the summer, Julius made his name in AAU competition, and once captured a national title on a squad that included future college teammates Brendan Haywood and Kris Lang.

As Julius’s high school career wound down, he faced a difficult decision. Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski recruited him heavily to play basketball for the Blue Devils, but Julius was pursued even harder by top football programs. The flood of mail he received from football coaches was of such magnitude, in fact, that Southern Nash assigned him his own mail slot in the school office.

The attraction was obvious. Projected as a defensive end, Julius was as fast as most receivers, stronger than most offensive lineman and had a motor that never stopped. (Davis still recalls a story from the summer of 1996 when the junior did backflips in full pads the length of the field after a grueling practice.)

Determined to have his cake and eat it too, Julius focused on schools close to home that would allow him to suit up in football and basketball. He ultimately picked North Carolina, where coach Carl Torbush offered Julius a full ride for his gridiron skills, and had no quams with him walking on to the Tar Heels hoops team. Julius was delighted to be attending the alma mater of his hero Jordan.

ON THE RISE

The teenager’s first year at Chapel Hill was more notable for what happened away from sports. Redshirted in football, he didn’t see a second of action for the Tar Heels on the gridiron, nor did he try out for the hoops team. He did, however, hook up with an academic advisor named Carl Carey. With a doctorate in educational psychology from UNC, Carey was a perfect mentor for Julius. He kept the freshman on track academically, making sure he attended classes and paid attention to his studies. Over the years, Carey would come to fill even more important roles for Julius, including steering him clear of shady agents and serving as a de facto business manager once he reached the pros.

Carey’s job wasn’t always an easy one. Julius assumed he was headed for a career in the NFL or NBA, so taking advantage of the edcuational opportunities before him at North Carolina wasn’t always as the top of his priority list.

Julius made his debut for the Carolina football team in the fall of 1999. Under Torbush, UNC appeared to be a program on the rise. The offense was led by quarterback Ronald Curry, a two-sport star shouldering the weight of fantastic expectations. The defense was where the team figured to be strongest. Senior linebacker Brandon Spoon was among the ACC’s best, and second-year tackle Ryan Sims was a star on the rise. With Julius set to take over at left end, opponents figured to have trouble moving the ball against the Tar Heels.

Unfortunately for Carolina, injuries ravaged the squad on both sides of the ball. Curry blew out his Achilles tendon, and Spoon tore a biceps. In turn, UNC finished a dismal 3-8. If it wasn’t for a late-season upset of NC State, Torbush likely would have been shown the door.

Julius was one of Carolina’s few bright spots. Named a freshman All-America by The Sporting News, he recorded a team-high six sacks and 10 tackles for a loss. Along with receiver Sam Aiken, he was voted one of the Tar Heels’ most outstanding newcomers.

When the football season ended, Julius immediately joined the Carolina hoops squad, which was just returning from the Maui Invitational in Hawaii. Coach Bill Guthridge found the redshirt freshman to be a great spark off the bench. Backing up his former AAU teammates Haywood and Lang, Julius used his power and quickness to wreak havoc in the paint. Against Clemson in January, he pulled down 13 rebounds in limited duty. Two weeks later, he logged crucial minutes in the second half of a victory over Florida State. Come March, with the post-season on the horizon, Julius scored a career-high 14 points versus Georgia Tech.

Going into the NCAA Tournament, the Tar Heels were rounding into shape. Ed Cota looked terrific at the point, freshman Joseph Forte emerged as the team’s leading scorer and the frontcourt was strong and physical. In the first round, UNC handled Missouri, with Julius scoring nine points and pulling down four rebounds. Next they faced the South’s #1 seed Stanford and pulled a major upset, 60-53. Again Julius was a key, presenting an intimidating presence in the paint with three blocks. The Cardinal starters up front shot a combined 7-for-29.

In the Sweet 16, Carolina held on to beat Tennessee, thanks in large part to Julius. When Haywood fouled out with six minutes remaining, Guthridge went to his super sub. Julius was awesome, grabbing five rebounds down the stretch and canning two crucial free throws. Next, the Tar Heels continued their amazing run with a 59-55 win over Tulsa to advance to the Final Four, where they met Florida. Though the team lost by 12 points to Gators, UNC fans were still giddy over their squad’s post-season success.

For Julius, his first year of hoops at Carolina provided thrills he never expected. It also caused him to miss spring football practice, which put him behind schedule learning the team’s defensive schemes. For the first time in his athletic career, Julius realized that splitting time between the two sports could present disadvantages.

Despite UNC’s poor gridiron finish in ‘99, there was reason for optimism in 2000. Curry was back from his injury, as was Spoon. Alge Crumpler had developed into one of the nation’s better tight ends, and freshman Michael Waddell was a stud prospect in the secondary. Even more promising was the tandem of Julius and Sims. Together they gave th Heels a surge along the line of scrimmage that stopped runners dead in their tracks and terrorized enemy passers.

Coach Torbush, however, failed to pull this talented group together, and it would end up costing him his job. Curry never quite seemed to get comfortable in the offense, and the Tar Heels struggled to score touchdowns. Though the defense ranked second in the conference, Carolina ended the season at just 6-5 and failed to earn a bowl bid.

During this up-and-down season, Julius established himself as one of the country’s most dominant defenders. He set a UNC record with 24 tackles for loss, and came within one sack of matching Lawrence Taylor’s school mark of 16 sacks. Voted to the All-ACC first team, he also earned first-team All-American honors from CNNSI.com and CollegeFootballNews.com.

As the campaign progressed, opponents were often forced to use only half the field because Julius was such a disruptive force. This was particularly true at Carolina’s Kenan Stadium. Indeed, visitors to UNC concentrated so intently on Julius that he did nearly all his damage on the road. Of his 15 sacks, all but two were registered away from home. After the season, the sophomore credited defensive line coach James Webster with much of his success.

Julius wasted no time trading in his cleats for kicks and joined the Carolina basketball team. New coach Matt Doherty was happy to see him. After the team’s Final Four appearance the previous spring, fans had pie-in-the-sky hopes for the 2000-01 campaign. The frontline returned intact, and Forte was a year older and wiser. While point guard was a question mark—Curry’s career had been uneventful thus far, causing everyone to wonder whether he was the real deal —the energetic Doherty was viewed as a real difference-maker.

The burden of heavy expectations, however, took its toll. By the time Julius suited up for basketball, the Tar Heels were sputtering. His impact was felt immediately. UNC beat UCLA in his first game back, then reeled off 14 more victories. In February, Doherty inserted Julius into the starting lineup. In his first career start, he pumped in 18 points against Maryland. Two weeks later he chipped in with 10 points as Carolina defeated NC State to clinch a share of the regular-season ACC championship.

Unfortunately, the post-season wouldn’t produce the same level of drama as the year before. In the NCAA Tournament, the Tar Heels raced by Princeton in the first round, but were dumped by Penn State in their next contest. In what would prove to be his final college basketball game, Julius recorded a double-double (18 pts, 10 rebounds) against the Nittany Lions. For the season, he averaged 7.1 points and 4.0 rebounds, and led the Tar Heels in field goal percentage (.643).

Now Julius had some serious thinking to do. Because of his hoops commitment, he had again seen limited action in spring practice, and it appeared more and more that his future path would lead to the NFL, not the NBA. New Carolina football coach John Bunting told him as much, as did pro scouts. Even his academic advisor, Carey, saw the wisdom of giving up basketball. All along he had been working to keep Julius focused on his classes, and the idea of working towards an NFL career reinforced the need to be disciplined in all phases of his life. Before the 2001 football season began, it was set: Julius was done with hoops, and he would apply for the NFL draft in 2002.

MAKING HIS MARK

Over the summer, Julius rededicated himself to football. Knowing that pro teams wanted to see more bulk on his 6-6 frame, he added 15 pounds of muscle. Meanwhile, he didn’t lose any of his quickness or flexibility. Indeed, his time in the 40-yard dash remained at 4.5 seconds, and his vertical leap stayed at nearly 38 inches.

For coach Bunting, Julius was a sight for sore eyes when he arrived at training camp. A former All-ACC linebacker at UNC, he knew he had his work cut out for him in his first year at the helm. The Tar Heels opened the campaign at Oklahoma against the defending national champs, then visited Maryland and Texas. Their reward for this murderous three-game road swing? A home tilt against Florida State.

Bunting came to Carolina with a new staff under him, including defensive coordinator John Tenuta and offensive coordinator Gary Tranquill. Among the top returnees at their disposal were Curry at quarterback, Willie Parker at running back, Sims along the defensive line, Waddell in the secondary, and Julius.

The junior got off to a rousing start against the Sooners, picking off a pass in the first quarter and rumbling 29 yards for a touchdown. But Oklahoma simply had too much talent for the Tar Heels, and won going away, 41-27. Julius finished with five tackles, including two stops behind the line of scrimmage.

The following week was almost a replay of the opener. Julius again had his way, making four tackles in the backfield and adding three sacks. But the Carolina offense couldn’t muster much of an attack, and the Tar Heels fell, 23-7. When UNC suffered a third-straight defeat at the hands of the Longhorns, the season teetered on the brink of disaster. Texas obviously studied the Oklahoma and Maryland films, as Julius was double- and triple-teamed all day long.

With the sixth-ranked Seminoles next on the schedule, Carolina faced a monumental test. Julius made sure the team passed. Leading the Tar Heels to a shocking 41-9 rout, he matched his career high with 10 tackles, including five for losses, and recorded his second interception of the year. For his effort, The Sporting News named him its Player of the Week.

The laugher over FSU sparked a four-game winning streak. Julius played a prominent role in each victory. Against NC State, he combined with teammate Joey Evans for a fourth-quarter sack of Wolfpack passer Philip Rivers, who coughed up the ball for a crucial turnover. The next week Julius did it on his own versus East Carolina. With the Tar Heels up by eight points late in the game, he sacked David Garrard to safeguard the victory. Against Virginia, Julius set the tone by dropping quarterback Matt Schaub in the first quarter.

His most impressive display came against Clemson. Woody Dantzler and the Tigers entered the game on a serious roll, accouting for 935 yards in their previous two contests. But in a 38-3 shellacking, UNC held Clemson to a season-low 209 yards of total offense. Julius made the play of the day in the second quarter, when he fought off two blockers, batted a pass straight in the air, then grabbed the loose ball as he was knocked to the turf.

The Tar Heels, however, couldn’t sustain their momentum, as consecutive losses to Georgia Tech and Wake Forest leveled their record to 5-5. To earn a bowl bid, the team would have to win its last two games. UNC responded with victories over Duke and SMU, and received an invitation to the Peach Bowl in the Georgia Dome against Auburn. In a defensive struggle, UNC overcame the Tigers 16-10.

Julius closed his college career with six tackles, including one for a loss, versus Auburn. Despite being the focal point of enemy game plans, he wound up the year with 63 tackles (19 behind the line of scrimmage), 9.5 sacks, three interceptions and nine deflected passes. He becamae the first player in Carolina history to win the Lombardi Award, and also took home the Chevrolet Defensive Player of the Year award and the Chuck Bednarik Award as the nation's best overall defensive player. The runner-up to Oklahoma's Roy Williams for the Bronco Nagurski Trophy, Julius was an easy choice as All-ACC First Team. In addition, he was named first-team All-America by the Associated Press, the Walter Camp Football Foundation, the America Football Coaches Association, CNNSI.com, Football News, and the Football Writers Association of America.

As the NFL draft approached, Julius had a pretty good idea of where he was headed. Initially, the Houston Texans had indicated great interest in him, but the expansion club shifted its thinking toward Fresno State quarterback David Carr. In turn, the Carolina Panthers felt like they had hit the lottery. Coming off a dreadful campaign—the team went 1-15, and fiished dead last in defense in 2001—the Panthers were looking to completely overhaul the club. Their first move was hiring John Fox as head coach. Formerly the defensive coordinator with the New York Giants, he wanted a franchise player to build around. Julius fit the bill, particularly given Fox’s attacking style of defense.

Selecting the Carolina product was also viewed as a marketing coup. In 2001, the Panthers had averaged nearly 25,000 no-shows per home contest, and the front office hoped the addition of a hometown hero would translate into better attendance figures. On draft day, after Houston tabbed Carr with the #1 pick, Carolina gabbed Julius. His agent, Marvin Demoff, negotiated a sever-year deal worth as much as $62 million with incentives.

Despite his team’s awful record in ‘01, Fox felt the roster had real potential. Michael Rucker was underrated at one defensive end, and with Julius lined up opposite him, the Panthers promised to put good pressure on the quarterback. Behind them, middle linebacker Dan Morgan was a former first-round pick, and strong safety Mike Minter was the leader of the secondary.

On the other side of the ball, offensive coordinator Dan Henning had to find out whether quarterback Chris Weinke could play in the NFL. If not, veteran Rodney Peete would step in for him. Their primary targets were recievers Muhsin Muhammad and Steve Smith, while the top runner in camp was Lamar Smith. The line blocking for the offense was expected to be steady, but hardly spectacular.

From the season’s opening kickoff, Fox’s influence on the Panthers was evident. They hustled all over the field, hit hard on defense and tried to avoid mistakes on offense. Carolina won its first three games, outscoring opponents 62-28.

Julius had a major impact. In Carolina’s first game, against the Baltimore Ravens, he batted a pass by quarterback Chris Redman that fluttered into Morgan’s hands to seal a 10-7 victory. A week later, he equalled a team mark when he sacked Detroit’s Mike McMahon three times.

Julius was even better in October, garnering honors as NFL Rookie of the Month after registering six sacks, one interception, three forced fumbles and 25 tackles. The Panthers, however, weren’t nearly as good. After their hot start, they dropped five in a row. The team’s losing ways continued into November, as Carolina’s winless streak reached eight straight.

The Panthers finally snapped their slump in December, beating the Cleveland Browns 13-6. That contest proved to be Julius’s last of the season. Days after the victory he failed a drug test because of a banned supplement containing ephedra. The league suspended him for the rest of the year.

Soon the rumors began that Julius was on the juice. He refuted the accusations, explaining that several times during the year he had taken an energy pill that he believed was legal. His goal was to hurdle the proverbial rookie wall by giving his tired legs a boost. Naive and uninformed, Julius trusted someone he barely knew (who hand-delivered the pills) and paid the price. Since this episode, Carey has become much more involved in just about every decision Julius makes.

Without Julius in the lineup, Carolina still managed a strong finish, taking three of their last four to go 7-9 and provide a glimmer of hope for 2003. That hope eventually grew to a belief that the Panthers might be in for a very special season. On the campaign’s opening Sunday, quarterback Jake Delhomme engineered a dramatic comeback to give the team a 24-23 victory over the Jacksonville Jaguars. A week later, Carolina won a defensive struggle in Tampa. The Panthers went on to take the NFC South with a record of 11-5.

Their divisional title was a surprise to most onlookers. Under Fox, the defense matured into one of the stingiest units in football. Morgan and Minter established themselves as rising stars, as did outside linebacker Will Witherspoon. The front four, however, was the team’s real strength. The quartet of Kris Jenkins, Brentson Buckner, Rucker and Julius proved as fearsome as they come. Each player was nearly impossible to block one-on-one, and as a group they developed a good feel for their coach’s aggressive system. Julius’s best stretch occurred in December, as he posted a sack in four straight games.

The offense, meanwhile, also found a nice rhythm. Delhomme had gained the confidence of his teammates, running back Stephen Davis—signed in the off-season as a free agent—enjoyed a Pro Bowl year, and receiver Steve Smith emerged as a dangerous threat on the outside. The line gelled as well, with guard Doug Brzezinski and tackle Jordan Gross keying the team’s fine work in the trenches.

Carolina drew the Dallas Cowboys in the first round, and completely dismantled them. In the 29-10 victory, Delhomme, Davis, Smith and Mushin Muhammad were spectacular, and the defense confused Dallas quarterback Quincy Carter all night long, pressuring him constantly and forcing him to throw under the coverage. Julius contributed with an interception that he returned 34 yards.

Up next were the Rams in St. Louis, a game few prognosticators thought Carolina could win. The home team controlled the action early, but the Panthers stiffened in the red zone to keep the score close. Then Delhomme got it going on offense. Though Davis went down with a leg injury, DeShaun Foster stepped up and confounded the Rams with his speed on the perimeter.

The Panthers appeared to put the game away in the fourth quarter, moving ahead 23-12. Marc Bulger, however, guided two late scoring drives that sent the contest into overtime. The extra session saw both teams fail on makeable field-goal opportunities. Those misses set up the play of the game, as Delhomme hit Smith on a skinny post, and the speedster did rest, racing 69 yards for a TD.

Despite Carolina’s impressive performance in St. Louis, the Eagles were the big favorite heading into the NFC Championship Game in Philadelphia. But again the Panthers defied the odds. This time the defense carried the load, dominating the Eagles for a 14-3 victory. Carolina picked off four passes, including a record-tying three interceptions by rookie Ricky Manning Jr. To the amazement of football fans nationwide, the Panthers were on their way to Super Bowl XXXVIII against the New England Patriots.

Excitement for the big game was difficult to muster. Indeed, many fans expected a boring defensive stalemate, as Fox matched wits with New England head coach Bill Belichick. Julius and his teammates were happy to let the contest unfold that way. They had surrendered just 36 points in three post-season games. The Panthers were certain they could contain the New England offense.

The game proceeded just as many suspected it would, until both offenses exploded late in the second quarter. Tom Brady threw a pair of touchdowns for the Patriots, while Delhomme and Smith beat the New England secondary for a scoring toss of their own. The action slowed in the third quarter, but built to a fever pitch in the last stanza. Trading big plays, including an 85-yard TD pass from Delhomme to Muhammad, the teams fought for control of the scoreboard.

Down 22-21—a deficit that could have been more had Fox not decided to go for two after Carolina’s first TD of the fourth quarter—New England stormed back to seize a seven-point lead. Delhomme answered by guiding his team expertly downfield to knot the score at 29-29. The only problem was that Carolina left too much time on the clock for Brady. That mistake was made even worse when John Kasay’s kickoff skidded out of bounds. By now, the Panthers were clearly laboring on defense. New England moved into field-goal range, then Adam Vinatieri converted for the second time in three years on a Super Bowl-winning kick. The stunned Panthers walked off the field on the wrong side of 32-29 final.

Even with its disappointing conclusion, the ‘03 season was a success for Julius. He entered the campaign unsure of how long the effects of his suspension would linger. Though he totalled 12 sacks in as many games in 2002—good for second among rookies and fourth in the NFC— and was named NFL Defensive Rookie of the Year by AP, Sports Illustrated, Pro Football Weekly and Football Digest, questions remained about whether he used performance-enhancing drugs. He brushed aside the speculation as absurd, but also admitted that it served as motivation for him.

As Julius hoped, that talk subsided as the year progressed. While his sack total dropped to seven in 2003, he became a more troublesome every-down player. In turn, fans and the media shifted their focus back to his play on the field.

After their gutty performance in the Super Bowl against the Patriots, big things were expected of Julius and the Panthers for the 2004 season. Flanked in the NFC South by the inconsistent Saints and the aging Buccaneers, and with Michael Vick learning a new offense in Atlanta, preseason prognosticators saw Carolina as the class of the division. The club returned nearly all of its key players, and added a couple of interesting rookies in wide receiver Keary Colbert and cornerback Chris Gamble. Fox's primary concern was the health of Davis. The Pro Bowl back was battling leg problems that threatened to hamper him all year long.

Much of the fanfare that surrounded the Panthers was dispelled in their season opener, a Monday Night tilt against the Packers. In a classic case of Murphy’s Law, whatever could go wrong did go wrong. Smith, Carolina's game-breaking receiver, broke his left leg and was lost for the year, while Davis was battered by the Green Bay defense. He would make only one more appaerance the rest of the campaign.The Packers ran all over the Panthers, rolling to a 24-14 victory.

The injuries to Smith and Davis were just the tip of the iceberg. In all, 11 Carolina players were placed on IR in '04. Not surprisingly, the Panthers staggered through the the season's first two months. After evening their record with a win over the Kansas City Chiefs, they dropped six in a row. A play by Julius in Denver summed up the team's struggles. With the Broncos driving into Carolina territory in the second half, he intercepted a pass in his own endzone. Seeing no one in front of him, Julius took off with thoughts of converting a 104-yard touchdown return. But he tired as he neared his goal line, and Denver receiver Rod Smith caught him, forced a fumble and recovered the loose ball. Though the Panthers challenged the call and the ruling was reversed, they fell, 20-17.

At 1-7, Fox searched for options in the running game, and eventually settled on Nick Goings as his feature back. Meanwhile, the combination of Delhomme to Muhammad revitalized the passing attack. On defense, Julius also spearheaded a rebirth.

The resilient Panthers fashioned a five-game winning streak that put them in the thick of the NFC Wild Card race. Julius was the catalyst. In a 21-14 win over Tampa Bay, he had a sack and returned a pick 46 yards for a score. Two weeks later, he was in the middle of a dominant performance against the Rams. His play was all the more amazing considering that opponents were now tailoring their game plans to stop him.

But Carolina's spirited run ended with a loss in Atlanta. Julius starred again in this one, grabbing a Vick fumble out of mid-air and rumbling 60 yards for a TD. The Falcon QB got his revenge, however, scoring on a neat scramble with time running out for a 34-31 victory. The Panthers split their last two games to finish up at 7-9.

For Julius, the '04 campaign was an important step in his maturation. His continued development as one of the league's most disruptive defensive ends was impressive enough. Indeed, he recorded 11 sacks, forced four fumbles, and earned a spot in the Pro Bowl and on the AP's All-Pro First Team. But it was his development as a leader that really opened eyes in Carolina. With Julius and Delhomme in the locker room, the Panthers now have two guys who can rally the troops when things go bad.

As even Julius might admit, life is grand again. Shy by nature, he is learning to deal with the media more effectively, and has a better understanding of who he should count among his friends. On the gridiron, Julius and his defensive mates upfront are recalling memories of some of the NFL’s most storied D lines. It seems that Julius has just scratched the surface of his awesome potential—which is the worst news quarterbacks around the league could hope for.

JULIUS THE PLAYER

There are few players in NFL history who have boasted the package of physical skills Julius possesses. At 6-6 and 285 pounds, he can run with wide receivers and overpower offensive linemen. Thanks to his years on the hardwood, he has quick feet and tremendous agility. He is such a gifted athlete that he could probably still find his way onto an NBA roster.

Julius’s only remaining obstacle is experience. He came into the NFL with four pass-rushing moves, and while he never needed his full assortment in college, the pros are a different story. Even if he doesn’t develop anything more than a bull rush and speed rush, he has to improve his technique to ensure he’s always maximizing his leverage.

Julius is an every-down player who loves the game. In college, he was accused of taking a play off here and there, a rap he wants to shed in the NFL. Part of his early success has been a result of John Fox’s defensive philosphy. He favors lining up his best defensive end on the left, which means Julius usually faces the opponent’s weakest tackle. His primary job is to disrupt the passing game.

Julius is quiet and reserved in his personal life. On the field, however, he has a competitive fire that runs hot. Teammates like and respect him. Opponents fear and respect him.

EXTRA

# In 2001, The Sporting News named Julius the country's Top Two-Sport Athlete (as voted by NCAA Division I coaches).

# Julius’s dunk off an alley-oop pass by Ronald Curry against Wake Forest was CNN/SI's "Play of the Day" on January 6, 2001.

# Only Greg Ellis had more sacks (32.5 from 1994 to 1997) in a career at North Carolina than Julius.

# Julius was only the second unanimous All-American in UNC history. The first was Lawrence Taylor in 1980.

# In 2002, Julius tied an NFL rookie record with two three-sack games. The mark was previously achieved by Leslie O'Neal with the San Diego Chargers in 1986.

# Julius was the first Panther to win the Associated Press NFL Defensive Rookie of the Year.

# Julius says he’s so concerned about unwittingly taking another banned substance that at restaurants he only drinks water, apple juice or orange juice.

# After Julius signed with Carolina, he bought a silver Mercedes-Benz G500 SUV for himself and a house for his mother in Durham.

# Among Julius’s nicknames are Pep and Big Head.

# On his left arm, Julius has a tattoo of a Tasmanian Devil holding a football in his left hand and a basketball in his right.