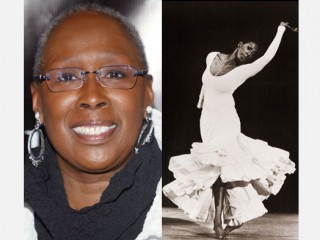

Judith Jamison biography

Date of birth : 1943-05-10

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-07-23

Credited as : Artist and dancer, choregrapher, director

5 votes so far

Since 1989 Judith Jamison has been at the helm of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in New York City. As the company's artistic director, she has blended her own standards of excellence with the late Ailey's artistic genius, remaining true to his vision of having black dancers perform pieces about African culture and the African-American experience. A protégée and friend of Ailey, Jamison strives to maintain his dance company and preserve his memory while constantly pushing the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater toward new horizons.

In 1965 Ailey saw Jamison perform and asked her to become a member of his dance company. Under Ailey's direction, the five-foot-ten, statuesque dancer was soon equated with an African goddess by reviewers and applauded by audiences from Paris to Moscow to New York. She was a lead performer in Ailey's company from 1967 to 1980, and Ailey choreographed some of his most famous works for her, most notably Cry, a three-part tribute to African-American women, in 1971.

He also encouraged her development as a choreographer during the 1980s. Jamison remained Ailey's friend even when she left his company to perform on Broadway and dance with other companies. When Ailey became ill in the late 1980s, he selected her to succeed him as artistic director of his company, which she did, even though she was in charge of her own dance ensemble at the time.

Jamison's career as a performer lasted almost twenty years; during that time, she learned more than seventy ballets. Aside from appearing primarily with Ailey's company in the United States and around the globe, she performed with the American Ballet Theatre, the Harkness Ballet, and other companies in the United States and overseas. She performed in Africa on a tour sponsored by the U.S. State Department and danced at several presidential inaugurations.

"I'm standing on Alvin's shoulders," Jamison reflected in her autobiography Dancing Spirit (1993); but after his death, she found that "the horizons [had] become broader." Under her direction, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater took on new dancers and varied its programs; in addition, Jamison introduced a choreographic style that is different from Ailey's. As Anna Kisselgoff observed in the New York Times, "The contemporary pieces are cool; the older ones simmer and come to a boil. Miss Jamison has added some new ingredients, but she has ... stirred the right brew."

Began Dance Training in Philadelphia

Jamison was born on May 10, 1943, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to John Henry Jamison and Tessie Belle Brown. She credits her parents for the start of her spiritual journey toward the arts and for her pride in her African-American heritage. Though she and her older brother grew up in a racially mixed, blue-collar neighborhood, their parents exposed them to Philadelphia's thriving black community. Aware of their young daughter's restless energy, Jamison's parents enrolled her in the Judimar School of Dance, where she performed in her first dance recital at the age of six.

Jamison went to Judimar for eleven years, while simultaneously attending regular public school. At Judimar, she studied ballet, tap, acrobatics, jazz, and primitive dance with a variety of teachers, including her earliest mentor, Marion Cuyjet. Jamison recalled in Dancing Spirit that Cuyjet "created a world for young black children that encompassed more than dance." Jamison also remembered the impact of seeing a lecture-demonstration given by anthropologist and dancer Pearl Primus. "She had gone to the [African] homeland, which impressed me," Jamison noted in her autobiography.

After graduating from Judimar and Germantown High School, Jamison took a year off before going to college. Then, at the suggestion of Cuyjet, she enrolled at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, on a physical education scholarship. Apparently Fisk was too conventional a place for an individualist like Jamison. "During halftime at basketball games I danced on pointe," she wrote in Dancing Spirit. "People thought I was totally nuts.... They didn't know what to make of me." After three semesters she transferred to the Philadelphia Dance Academy, which offered her more opportunity to challenge herself as a dancer.

While studying in Philadelphia, Jamison took a class with a guest teacher, the innovative theatrical choreographer Agnes de Mille, who promptly offered her a role in a ballet she was choreographing for the American Ballet Theatre. "I said yes," Jamison wrote in her autobiography. "I knew Agnes de Mille and her history and I knew the Ballet Theatre and their[s]. I had pictures of the dancers all over my bedroom wall." Called The Four Marys, the ballet was performed in 1965 at New York City's Lincoln Center and at the Chicago Opera House. Afterward, Jamison stayed in New York and frequented audition halls, looking for parts. At an unsuccessful audition for a role in a Harry Belafonte television special, she attracted the interest of Ailey, who several days later asked her to join his Dance Theater. Commenting on the years she spent working with Ailey, Jamison revealed in Dancing Spirit, "My relationship with Alvin was based on total awe of his accomplishments as a director, choreographer, and human being."

Joined Ailey's Dance Theater

Jamison first danced with Ailey's company in the ballet Congo Tango Palace, which was performed at the Harper Theatre Dance Festival in Chicago in 1965 and 1966. She traveled continually afterwards, appearing onstage across America, Europe, and Africa as Ailey's company gained worldwide attention. "We did six weeks of one-night stands on our bus tours," Jamison explained. "Alvin would teach us a half-dozen dances in two weeks." When the Ailey company temporarily broke up in Barcelona, Spain, because of lack of funding, Jamison took time off and appeared in the African-French documentary film Batouk in 1967. She rejoined the company later that year and toured with them in Europe.

Jamison's height and strength, coupled with her ability to express a wide range of emotions, made her a preferred dancer; she performed key roles with the Ailey company, as in the famous solo Cry, which premiered in New York City in the spring of 1971. Of that performance Clive Barnes wrote in the New York Times, "For years it has been obvious that Judith Jamison is no ordinary dancer.... Now Alvin Ailey has given his African queen a solo that wonderfully demonstrates what she is and where she is.... Rarely have a choreographer and dancer been in such accord."

In 1980 Jamison left Ailey's company to star with Gregory Hines on Broadway in Sophisticated Ladies. Jamison also appeared with other dance companies and with leading male dancers, including Mikhail Baryshnikov. In addition she choreographed her own ballets for various companies, including that of Maurice Béjart in Paris, had lead roles created for her in the Vienna Opera, and taught dance classes at Jacob's Pillow in Massachusetts.

Of her decision to leave the Ailey company, she wrote in her autobiography, "I had finished doing my work dancing with the company. I wanted to try something else." Yet Jamison's ties to Ailey were not completely severed when she went out on her own. Prior to Ailey's death, Jamison explained to Olga Maynard in Judith Jamison: Aspects of a Dancer, "Alvin and I have this love-hate thing, a relationship that I think we both appreciate, if neither of us truly understands it." In 1984 she choreographed her first piece, Divining, at Ailey's suggestion, andperiodically returned to perform an occasional piece with the company.

Assumed Leadership of the Ailey Company

In 1988 she began auditioning dancers for her own troupe, the Jamison Project, which was based in Philadelphia and Detroit. Two premiere dances were created for the project, Forgotten Time and Read Matthew 11:28. When the company first performed them in Washington, D.C., Suzanne Levy observed in the Washington Post, "These 12 dancers have been coached by Jamison to give their all. Bodies are flung with fierce disregard for safety, limbs are stretched to improbable limits, stops are made with jolting abruptness, the movement is impossibly fast, yet, they do it, and they make it look exhilarating rather than dangerous." Jamison planned to give tours, workshops, seminars, and lecture-demonstrations in each city. Before her project blossomed, however, Ailey died, and Jamison took up her position as artistic director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. She managed both companies for a time, but eventually hers merged with Ailey's.

Jamison's choreography drew both praise and criticism in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1985 Dance Magazine called her "first foray into choreography, Divining, a deceptively simple exercise in strong, grounded movement to a live percussion score.... A fusion of traditional African motifs with the repetitive, simplified focus of post-modern dance, the work has more to it than meets the eye." At the opposite pole, New York magazine termed it "a flimsy affair," adding, "The piece doesn't go on anywhere near long enough to build the hypnotic power it lays claim to."

When the premiere of Jamison's 1989 work Forgotten Time was performed at New York's Joyce Theater, Jack Anderson wrote in the New York Times, "Ms. Jamison was at her choreographic best.... The work, for her full company, was notable for the beauty of its groupings and for the way it appeared to take place in some mysterious, transcendent realm." However, he added that Jamison was "not always able to organize [her sequences] into choreographic structures" and suggested that "judicious editing would make some of her works even more striking than they now are."

During the winter 1993-94 season of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Jamison presented a new work, Hymn, set to a monologue created by actor/writer Anna Deavere Smith. About the choreography of the piece, which was performed at the company's thirty-fifth anniversary gala at City Center in New York City, Deborah Jowitt wrote in the Village Voice, "Jamison can make the whole stage boil with individual gestures or lock into exuberant, spine-rippling unison. She uses walking to reflect Ailey's words about dance as a spiritual journey or interpolates familiar Ailey images ... into her own solid patterns." Kisselgoff observed in the New York Times, "Hymn threatened to be all talk and little dance.... Yet, gradually and dramatically, [it] progressed into a convincing artistic statement of its own.... Ms. Jamison has choreographed pungent solos [and] captures the essence of some outstanding dancers."

Furthered Company's Artistic and Financial Success

While she continued to choreograph new works, Jamison served a more important role as a catalyst for the dance theater's artistic and educational achievements, its renewed financial stability, and its role as a global popularizer of the art form. Jamison championed the development of the Women's Choreography Initiative and helped establish a multicultural curriculum at the Ailey School, introducing dance from India and West Africa. In 1998 she helped launch a bachelor of fine arts program in conjunction with Fordham University, which offered dance training combined with a liberal arts education. A savvy businesswoman, Jamison helped turn a $1 million deficit into a $25 million endowment while building the Ailey organization's first permanent home at a cost of $54 million. The largest building in the United States devoted exclusively to dance, the space spreads over eight floors and encompasses a 250-seat theater, twelve studios, a physical therapy room, a costume shop, administrative offices, and media center. The Ailey group performed at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, Georgia, and the 2002 Olympic Arts Festival in Salt Lake City, Utah, where Jamison carried the torch as part of the pre-event relay.

Under Jamison's direction the company performs around the world on what Sarah Kaufman of the Washington Post called "a numbing year-round schedule." Their travels have included a historic residency in South Africa after the country abolished its policy of apartheid; a performance at the White Nights Festival in St. Petersburg, Russia; and an appearance at the Les étés de la danse de Paris festival in France. In a much-quoted remark, dance critic Kisselgoff of the New York Times commented that the Ailey dance company's "phenomenal popularity is unmatched by any other company in the world." By 2008 the Ailey organization estimated that its performances had been seen by approximately twenty-one million people in seventy-one countries; their promotional materials maintained, accurately, that "the company has earned a reputation as one of the most acclaimed international ambassadors of American culture, promoting the uniqueness of the African-American cultural experience and the preservation and enrichment of the American modern dance." In February of 2008 Jamison announced that she would step down from her position as artistic director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 2011. She planned to remain associated with the troupe as director emerita.

Jamison has been showered with a seemingly endless succession of awards, including a Paul Robeson Award, an American Choreography Award, an Emmy Award, Kennedy Center Honors for her contributions to American culture, a National Medal of Arts, and honorary doctorates from Harvard and Howard Universities. In 2005 she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In her autobiography, Dancing Spirit, Jamison summed up her philosophy about what it means to be a dancer: "You have to be desperate, as though you were catching your breath.... You want to eat life, so you have to be famished all the time, not physically, but in wanting to know and in wanting to absorb and in exploring and stepping out over the edge, sometimes by yourself.... Dance is bigger than the physical body.... When you extend your arm, it doesn't stop at the end of your fingers, because you're dancing bigger than that; you're dancing spirit. Take a chance. Reach out. Go further than you've ever gone before."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born May 10, 1943, in Philadelphia, PA; daughter of John Henry and Tessie Belle Brown Jamison; married Miguel Godreau(a dancer), 1972 (divorced, 1974). Education: Studied dance with Marion Cuyjet, Nadia Chilkovsky, Joan Kerr, Antony Tudor, and others; attended Judimar School of Dance, Fisk University, and the Philadelphia Dance Academy. Memberships: National Endowment for the Arts, board member, 1972-76; American Academy of Arts and Sciences, fellow, 2005--; Jacob's Pillow, board member; Harkness Center for Dance Injuries, advisory board member. Addresses: Office--Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, The Joan Weill Center for Dance, 405 West 55th St., New York, NY 10019.

AWARDS

Selected awards: New York State Governor's Arts Award, 1998; Kennedy Center Honor, 1999; Prime Time Emmy Award and American Choreography Award for Outstanding Choreography in the PBS special A Hymn for Alvin Ailey, 2001; National Medal of Arts, 2001; "Making a Difference" Award, NAACP, 2004.

CAREER

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, principal dancer, 1965-80; Jamison Project, founder and artistic director, 1988-91; Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, artistic director, 1989--. Danced with the Harkness Ballet, 1966-67, and appeared as guest artist with the American Ballet Theatre, 1976, Béjart's Ballet of the Twentieth Century, 1979, and others. Appeared on television, including Ailey Celebrates Ellington (CBS), 1974; The Dancemaker: Judith Jamison (PBS), 1988, and others. Starred in Broadway show Sophisticated Ladies, 1980. Choreographed works include: Divining, 1984; Forgotten Time and Read Matthew 11:28, 1989; Hymn, 1993; Reminiscin', 2005, and others.