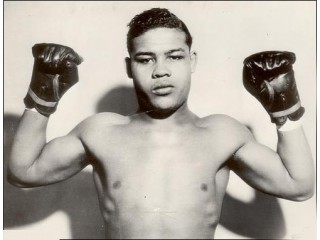

Joseph Louis Barrow biography

Date of birth : 1914-05-13

Date of death : 1981-04-12

Birthplace : LaFayette, Alabama, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-07-12

Credited as : Professional boxer, ,

4 votes so far

In his day, heavyweight champion Joe Louis was the most famous black man in America, virtually the only one who regularly appeared in the white newspapers. By breaking the color barrier that had been imposed on boxing after black heavyweight Jack Johnson outraged white sensibilities, Joe Louis began a process that would eventually open all of big-league sports to black athletes. Throughout his unprecedented twelve-year reign as world heavyweight champion, Louis projected a power inside the ring and a quiet dignity outside of it that would transform him from a black hero, obsessively identified in the white media with his race and alleged "savagery," into a national hero, and ultimately a sports icon. His later years were difficult, marked by financial worries and bouts with mental illness, but when he died, millions mourned his passing. As Muhammad Ali put it, "Everybody cried."

Growing Up

Part of Joe Louis' appeal lay in his rags to riches story. The seventh of eight children born to Alabama tenant farmers Munroe and Lillie Barrow, Joe lost his father early on. Two years after Joe's birth, Munroe Barrow was confined to the Searcy State Hospital for the Colored Insane, and Lillie was soon informed that he had died. In fact, Munroe lived on for another twenty years, an invisible man oblivious to his son's growing reputation. Believing herself a widow, Lillie Barrow soon married Pat Brooks, a widower with five children of his own. For a while Joe and the other children helped their parents work the cotton fields, but in 1926 the Brooks/Barrow family joined the growing swell of black migration northward.

The family resettled in Detroit, where twelve-year-old Joe found himself woefully unprepared for school. To his embarrassment, he was placed in classes with younger, smaller children, and eventually the school system shunted him off to the Bronson Vocational School. Fortunately for him, he discovered a vocation that would take him far beyond the precincts of the Detroit school system. When the Depression threw his stepfather out of work, Joe began doing odd jobs around town and hanging around with a rough crowd. To keep him off the streets, his mother scraped together 50 cents a week for violin lessons, but Joe used the money to join the Brewster Recreation Center, where he took up boxing.

Fearing that his mother would discover where the "violin money" was going, Joe dropped the Barrow from his name and began boxing neighborhood kids as Joe Louis. While he showed great promise, an exhausting, full-time job pushing truck bodies at an auto-body plant left him little time or energy for training. In late 1932, he entered his first amateur match against Johnny Miller, a member of that year's Olympic boxing team. Louis' lack of training showed, and Miller knocked him down seven times in the first two rounds. Mortified, Joe Louis gave up boxing altogether, taking his stepfather's advice to concentrate on his job instead. Interestingly, it was his mother who encouraged him to get back into the ring, seeing in boxing a chance for him to make something of himself doing what he enjoyed.

The Amateur Years

This time, Joe Louis quit his job and focused on his training. He returned to the amateur circuit, winning fifty of fifty-four matches over the next year, forty-three by knockouts. This impressive record soon brought him to the attention of John Roxborough, known throughout Detroit's black ghetto as the king of the numbers racket. Roxborough's other career was as a civic leader, sponsoring a number of charitable causes and helping local youngsters fulfill their dreams. He decided to take Joe Louis under his wing, even moving him into his house, putting him on a proper diet, and getting him some decent training equipment.

In June of 1934, on the verge of going pro, Joe Louis asked Roxborough to become his manager. To help fund Louis' career, Roxborough brought in Chicago numbers runner Julian Black, a longtime business associate. Together, they brought Louis to Chicago to train under Jack Blackburn, who had already taken two boxers to world championships. Those boxers, however, were white. The fact was that black boxers had very little chance of getting a shot at the title, particularly in the heavyweight division. Racism and segregation were endemic to American society, but in boxing there was a special reason that blacks were virtually ruled out as heavyweight contenders. That reason was Jack Johnson, who had held the heavyweight championship from 1908-1915.

Johnson was the first black heavyweight champion, and he reveled in the distinction, flouting white conventions by gloating over defeated white opponents, consorting openly with white prostitutes, and marrying white women. For seven years he defended his title against a series of "great white hopes," but in 1915 he finally lost to one of them, Jess Willard, in a match that may have been fixed. The white press openly rejoiced, and white boxing promoters and fighters vowed never to give another black man a shot at the title.

Given this history, Blackburn was reluctant to take on a black boxer, but he needed a job and Roxborough and Black promised him a "world beater." Blackburn put Louis on a strict training regimen, including running six miles a day, and trained him in a style that combined balanced footwork, a strong left jab, and rapid fire combination punches. At the same time, his management team carefully nurtured an image designed to draw a sharp contrast between Joe Louis and Jack Johnson. Louis was to be gracious before and after a fight, conform to an image of God-fearing, clean-living decency, and above all avoid outraging white opinion by dating white women. Together, training and image building would propel Joe Louis to a shot at the title.

Turning Pro

Joe Louis' first pro boxing match took place on July 4, 1934, when he knocked out Jack Kracken in the first round. By October 30th of that year, when he knocked out Jack O'Dowd in the second round, he had won nine straight matches, seven of them by knockouts. Along with his reputation, his payments were growing, from $59, to $62, $101, $250, $450, in the midst of the Depression when most of his old neighborhood was struggling on relief and occasional work. Louis was conscientiously sending money home to support his family, but he also began to develop spending habits that would plague him in later years, buying expensive suits and a shiny black Buick he would use to cruise for girls on visits home.

It was soon clear that Louis had outgrown these carefully chosen opponents designed to nurture his early career. Louis' managers began to look around for tougher competition, and soon settled on Charlie Massera, ranked eighth in Ring magazine's survey of top heavyweight contenders. On November 30, 1934, Louis met Massera, knocking him out in the third round. Two weeks later, he went up against Lee Ramage, another up-and-coming heavyweight, and a real challenge for Louis. Ramage was quick on his feet and accomplished in defense. For the first few rounds he managed to fend off Louis' powerful jabs, and between rounds Blackburn advised Louis to start hitting Ramage's arms, if he couldn't reach anything else. Eventually, Ramage was too tired to lift his arms, and Louis got him against the ropes, knocking him out in the eighth round.

Roxborough decided Louis was ready for the big time, and that meant New York's Madison Square Garden, which had controlled big-league boxing since the 1920s, when it sewed up contracts with all the major heavyweight contenders. And that presented a major difficulty. Jimmy Johnston, the flamboyant manager of Madison Square Garden, said he could help Louis, but Roxborough had to understand a few things. As a Negro, Joe Louis wouldn't make the same as the white fighters, and more ominously, he "can't win every time he goes in the ring." In effect, he was telling Roxborough that Louis would be expected to throw a few fights. That went against one of Roxborough's commandments: no fixed fights, and he hung up on Johnston. Fortunately for them, Johnston's monopoly was getting a little shaky.

A man by the name of Mike Jacobs would prove their salvation. Passed over for leadership of the Madison Square Garden Corporation, Jacobs had been looking for a way to break the Garden's monopoly, and in a bizarre series of maneuvers surrounding a New York charity, he found it. Traditionally, Madison Square Garden had hosted a few boxing competitions for Mrs. William Randolph Hearst's Milk Fund for Babies. The Fund got a cut of the profits, and Garden boxing got good publicity from Hearst's powerful papers. When the Garden decided to raise the rent on Milk Fund events, some enterprising Hearst sportswriters, including Damon Runyan, decided to form their own corporation to stage boxing matches in competition with the Garden, with a share of the proceeds to go to the Fund. They could provide the publicity, but they needed an experienced promoter, so they brought in Jacobs, forming the 20th Century Club. Officially, Jacobs held all the stock, as the sportswriters didn't want to be publicly identified with matches they'd be covering.

In the meantime, Joe Louis' winning streak continued. On January 4, 1935, he defeated sixth-ranked Patsy Perroni, and a week later he beat Hans Birkie. Mike Jacobs needed a serious contender to get his Club off the ground, and before long the name of Joe Louis came to his attention. He went to Los Angeles to witness a rematch between Louis and Ramage, and this time Louis knocked Ramage out in the second round. Impressed, Jacobs invited Louis to fight for the 20th Century Club, assuring his managers that "He can win every fight he has, knock 'em out in the first round if possible."

The Brown Bomber

Jacobs promoted a few "tune-up" fights for Joe Louis out of town, while his secret partners in the Club began to churn out the publicity that would eventually make Louis a household name. Scouting around for an opponent for a big New York match, Jacobs hit upon Italian Primo Carnera, a former heavyweight champion. The match was scheduled for June 25, 1935--and the timing couldn't have been better. Throughout the summer, Mussolini had been threatening to invade Ethiopia, one of the very few independent black countries. Feelings ran high throughout the international community, and particularly among black Americans. In the prematch publicity, Jacobs sold Louis as a kind of ambassador for his race, and by the time of the fight, black as well as white were deeply curious about this heavyweight contender crossing the color line.

More than 60,000 fans, and 400 sportswriters, poured into Yankee Stadium that night to see six-foot, one-inch Joe Louis, weighing in at 197 pounds, take on the six-foot, six-inch, 260-pound Italian giant Carnera. After a few lackluster rounds, they saw something amazing. Starting in the fifth round, Joe Louis came out swinging, nailing Carnera with a right that bounced him off the ropes, then a left, and another right. Only hanging onto Louis kept Carnera from going down. In the sixth round, Louis knocked him down twice for a count of four, but each time Carnera staggered to his feet. Finally, Carnera had had enough, collapsing against the ropes. The referee called the fight.

Overnight, Joe Louis became a media sensation, and Americans awoke to a rare phenomenon: a black man in the headlines. Naturally, commentators focused overwhelmingly on his race, hauling out a seemingly limitless supply of alliterative nicknames to characterize the newly prominent contender: "mahogany mauler," "chocolate chopper," "coffee-colored KO king," "saffra sandman," and one that stuck, "The Brown Bomber." Sportswriters played up and exaggerated Louis' Alabama accent and limited education to convey an impression of an ignorant, lazy "darkie" incapable of anything but eating, sleeping, and fighting.

At the same time, many sportswriters peppered their columns with dehumanizing savage references. For Davis Walsh, "Something sly and sinister and perhaps not quite human came out of the African jungle last night to strike down and utterly demolish Primo Carnera." Grantland Rice wrote in the Baltimore Sun, "His blinding speed, the speed of the jungle, and instinctive speed of the wild, was more than Carnera could face . . . Louis stalked Primo as the black panther of the jungle stalks his prey." Even New York Daily News sports editor Paul Gallico, widely viewed as a cultured liberal often sympathetic to black athletes, seemed overwhelmed and a little unhinged by Joe Louis. After watching a training session, he wrote: "I had the feeling that I was in the room with a wild animal. . . . He lives like an animal, fights like an animal, has all the cruelty and ferocity of a wild thing. . . . I see in this colored man something so cold, so hard, so cruel that I wonder as to his bravery. Courage in the animal is desperation."

Getting a Shot at the Top

Cruelty and laziness had nothing to do with the real Joe Louis, as his management team well knew, but it would take more than the truth to change the image. A combination of skillful public relations and external factors would be needed to transform the Brown Bomber into a national hero embraced by all segments of society. Fortunately for Louis, the public relations aspects were in the hands of skilled management team that had been successfully crafting Louis' image from the beginning. With his sudden rise to fame, they went so far as to release to the press a series of "seven commandments" that Joe Louis had lived by, rules that many newspapers would use in shaping their own coverage.

Other factors were out of Joe Louis' control, but worked to his advantage. Among these was the sorry state of boxing. Riddled by scandal and lackluster champions, professional boxing had been losing fans since the retirement of Jack Dempsey in 1929. Boxing was hungry for an exciting champion, and Louis' undeniable power in the ring and his willingness to fight any serious contender fit the bill.

And far beyond boxing's precincts, world events were undermining America's racial worldview. In Germany, Nazism's aggressive trumpeting of Aryan superiority was beginning to irritate many Americans, who started to ask themselves hard questions about what exactly they found offensive in the doctrine. Together, these factors began to soften the rigid color line that had prevailed in heavyweight title competitions for twenty years.

Another twist of fate would put Louis in sight of the championship, and dissolve that color line. Just weeks before Louis beat Carnera, James Braddock had defeated reigning heavyweight champ Max Baer in one of boxing's biggest upsets. Assuming a Baer victory against a challenger who'd lost twenty-six fights in his career, the Garden's Jimmy Johnston had made a fatal contractual error. He had signed Baer to the standard contract, obligating him to fight his next match in the Garden only if he won. Mike Jacobs went to work on Max Baer, eventually signing him up to fight Lewis on September 24, 1935.

But Louis had personal business to attend to first. That day he married Marva Trotter, a 19-year-old secretary at a newspaper, beautiful, intelligent, well-spoken, and perhaps most important to his managers, black. As Louis put it in his autobiography, "No Jack Johnson problem here." The new Mrs. Louis had a ringside seat when Max Baer was counted out in the fourth round when he refused to stand up from one knee. Later Baer told a reporter, "I could have struggled up once more, but when I get executed, people are going to have to pay more than twenty-five dollars a seat to witness it."

The Schmeling/Louis Matches

With his victory over Baer, Joe Louis was widely seen as the best fighter, and his drawing power eclipsed that of the hapless James Braddock. But there was another white hope on the horizon. Former heavyweight champion Max Schmeling

Louis and his fans were devastated, but not for long. The next year, it was Louis, not Schmeling, who got a shot at the championship. Partly this was due to events in Schmeling's homeland. Many Americans had been disgusted by Hitler's attempt to use sporting events, such as the 1936 Berlin Olympics, as a showcase for Nazism and Aryan superiority, and Hitler touted Schmeling's victory over Louis as "proof" of that superiority. Financial considerations also played a role, and when Mike Jacobs offered James Braddock a share of future proceeds from Louis' fights, he agreed to a match. Incredibly, there was virtually no outrage at this "violation" of the color barrier. Clearly, boxing in America had come a long way. On June 22, 1937, Joe Louis knocked out Braddock in the eighth round, becoming the World Heavyweight Champion.

Everyone knew a Schmeling rematch was the next order of business if Louis' title was to be seen as fully legitimate. A year later, on June 22, 1938, it came. The buildup to the match was incredible, even by the standards of the most famous black man in America. The world was on the verge of war with Nazism, and Max Schmeling was seen as an Aryan poster boy. For the first time, white and black America were united behind Joe Louis, proof that America's best could defeat Germany's. Louis had a simple strategy for the fight: unrelenting attack. From the beginning Louis came out swinging, landing an overhead right that stunned Schmeling, breaking two of his verterbrae with a roundhouse right, and knocking him down three times in rapid succession. Two minutes and four seconds into the match, Schmeling's trainer threw in the towel. Seventy-thousand fans hailed Joe Louis as an American hero.

A National Hero

Between the Schmeling match and the outbreak of World War II, Joe Louis would defend his title fifteen times against opponents who were so clearly outmatched they were nicknamed the "Bums of the Month." Only light-heavyweight champion Billy Conn seemed to offer any kind of challenge, taking Louis thirteen rounds to defeat on June 18, 1941. Before the match, Joe Louis introduced a memorable phrase into the American lexicon by declaring of Conn, "He can run, but he can't hide."

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Joe Louis enlisted in the U.S. Army, cementing his reputation in white America. The army sent him on a series of exhibition matches for the troops, as well as speaking engagements. Twice he donated the proceeds from title fights to the Navy Relief Fund. At the same time, he worked quietly to desegregate the armed forces, often participating in interracial events.

When Joe Louis left the service in 1945, he was at the peak of his popularity. He was finally accepted as an all-American hero, and in press coverage, words like "integrity" and "dignity" took the place of the old savage stereotypes. He successfully defended his championship against all comers, earning huge purses and retiring undefeated in 1949 after the longest reign of any boxing champion in history. His legendary generosity to his family, old neighborhood friends, and virtually any worthy black cause, endeared him to the public.

But below the surface, things were not always so good. His constant womanizing, carefully shielded from the press, had taken its toll on his marriage. In 1945, he and Marva divorced. They remarried a year later, but finally called it quits in 1949. His generosity also took a toll, and throughout the war he'd actually had to borrow significant sums from his managers. Even more alarming, he owed hundreds of thousands of dollars in back taxes. A year after his retirement, financial considerations forced him back into the ring. He went up against the new heavyweight champion, Ezzard Charles, on September 27, 1950, losing in a fifteen-round decision. On October 26, 1951, he made one last comeback attempt, losing to future champion Rocky Marciano in an eighth-round knockout.

Declining Years

For the rest of his life, Joe Louis would struggle with financial difficulties. Money came from personal appearances, exhibition matches, and even a mercifully brief stint in professional wrestling. From 1955 to 1958, he was married to Rose Morgan, a successful beautician with her own business who could foot most of the bills. In 1959, he married attorney Martha Malone Jefferson, moving into her home in Los Angeles. Under political pressure, the IRS settled with Louis for payments of $20,000 a year on taxes owed, but even that sum remained out of reach.

In the 1960s, Louis' life began to unravel. He took up with a prostitute, identified as "Marie" in his autobiography, who presented him with a son in December of 1967. The Louises adopted the boy, naming him Joseph. At the same time, Louis began to get involved with drugs, including cocaine, and began to show signs of mental illness, warning his friends and family of plots against his life. For a few months, he was committed to a mental institution in Colorado. Martha stuck by him, and with her help and encouragement, he quit cocaine. Unfortunately, his paranoid delusions continued intermittently, though much of the time he was his old, genial self.

In 1970, Caesar's Palace, in Las Vegas, hired him as a greeter, a job which involved signing autographs, betting with house money when the action seemed a little slow, and playing golf with special guests. The job suited him, and the casino even provided him housing, as well as $50,000 a year. Joe Louis lived and worked at the Palace until a massive heart attack felled him on April 12, 1981.

Joe Louis' funeral became a huge media event. A nation that had almost forgotten him suddenly remembered everything he had meant, hailing him anew as a great boxer who had restored class and integrity to professional boxing. Three thousand mourners gathered to hear tributes from speakers like Jesse Jackson, who saluted Joe Louis for "snatching down the cotton curtain" and opening up the world of big-league sporting to black athletes. Perhaps the greatest tribute came from Muhammad Ali, who told a reporter: "From black folks to red-neck Mississippi crackers, they loved him. They're all crying. That shows you. Howard Hughes dies, with all his billions, not a tear. Joe Louis, everybody cried."

AWARDS

1933, Won 50 of 54 amateur boxing matches, 43 by knockouts; 1935, Won 20 of 20 professional boxing wins, including defeats of former world heavyweight champions Primo Carnera and Max Baer; 1935, Associated Press "Athlete of the Year" award; 1936,1938-39,1941, Ring magazine's "Boxer of the Year"; 1937-49, World Heavyweight Champion, longest reign in boxing history; 1941, Edward Neil Memorial Plaque (for man who contributed the most to boxing); 1993, First boxer honored on a U.S. postage stamp.

CHRONOLOGY

* 1914 Born May 13 in LaFayette, Alabama

* 1926 Moves to Detroit, Michigan

* 1932 Fights first amateur boxing bout

* 1934 Moves in with John Roxborough, asks Roxborough to become his manager

* 1934 First professional boxing match, July 4

* 1935 Defeats Italian Primo Carnera, June 25, and becomes media sensation

* 1935 Marries Marva Trotter, September 24

* 1935 Defeats Max Baer to become top heavyweight contender, September 24

* 1936 Loses to German Max Schmeling, June 11

* 1937 Becomes World Heavyweight Champion, defeating James Braddock on June 22

* 1938 Defeats Max Schmeling in rematch, June 22, becoming national hero

* 1942 Enlists in U.S. Army

* 1945 Enlistment ends in October

* 1945 Divorces Marva Trotter

* 1946 Remarries Marva

* 1949 Divorces Marva

* 1949 Retires as undefeated World Heavyweight Champion

* 1950 Loses comeback attempt against new heavyweight champion Ezzard Charles, September 27

* 1951 Last professional boxing match, loses to Rocky Marciano, October 26

* 1955 Marries Rose Morgan, a successful beauty shop operator, on December 25

* 1958 Divorces Rose

* 1959 Marries attorney Martha Malone Jefferson

* 1967 Louises adopt a baby boy, naming him Joseph. Apparently, this the child of Joe Louis and a New York City prostitute, identified as "Marie" in Louis' autobiography. Martha would go on to adopt three more of Marie's children, of unknown paternity.

* 1970 Committed temporarily to Colorado state mental institution

* 1970 Takes position as greeter at Caesars Palace, Las Vegas, Nevada

* 1981 Dies of massive heart attack on April 12