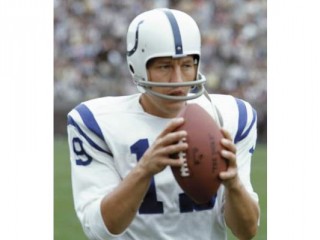

Johnny Unitas biography

Date of birth : 1933-05-07

Date of death : 2002-09-11

Birthplace : Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2011-08-09

Credited as : Former football player, The Golden Arm, Pittsburgh Steelers (1955)* Baltimore Colts (1956-1972) San Diego Chargers (1973) *Offseason and/or practice squad member only

Known as "The Golden Arm", Johnny Unitas is considered to be one of the best quarter backs to ever play in the National Football League (NFL). As a member of the Baltimore Colts, he played in what is arguably the greatest game in NFL history. In 1958, Unitas led his team to a championship in the first overtime and first nationally-televised game in the NFL.

John Constantine Unitas was born on May 7, 1933, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He was the third of fourth children born to Leon and Helen Unitas, who were of Lithuanian descent. Leon Unitas had a small business delivering coal, but he died when Unitas was five years old. Helen Unitas supported her family by taking over her late husband's business, as well as working odd jobs. She took accounting courses at night so she could also work as a bookkeeper. Despite his humble background, Unitas wanted to be a professional football player as early as age 12. He played quarterback for his school's team, St. Justin's High School. By the time he was a senior, Unitas was recognized locally for his talent and named to the All-Catholic High School team in Pittsburgh.

After graduating from St. Justin's in 1951, Unitas had a hard time finding a college team that was interested in him. He was considered small. Though he might have entered the University of Pittsburgh on scholarship, Unitas failed the entrance exam. He was offered a scholarship to the University of Louisville, which he took. At Louisville, Unitas toiled in obscurity, but he also grew two inches and gained 56 lbs. While a senior, Unitas married long-time girlfriend, Dorothy Jean Hoelle. They eventually had five children: Janice, John Constantine, Jr., Robert, Christopher, and Kenneth. Unitas graduated from the University of Louisville in 1955.

After graduation, Unitas's hometown team, the Pittsburgh Steelers, picked him in the ninth round of the college draft. However, the team cut Unitas before he even appeared in an exhibition game. He did not give up on a professional career. Unitas moved to Bloomfield, New Jersey and found work on construction sites, primarily as a pile driver. He also played quarterback for the Bloomfield Rams for $6 per game, on fields that were often covered with litter. Of this stage in his career, Unitas told Paul Zimmerman of Sports Illustrated, "They called it semipro football. Actually it was just sandlot, a bunch of guys knocking the hell out of each other on an oil-soaked field under the Bloomfield Bridge." Unitas's abilities on the field did not go unnoticed, however. A fan brought him to the attention of the Baltimore Colts of the National Football League.

Unitas was given a tryout by the Colts, and signed to a contract as a back-up to their quarterback, George Shaw. He got his break early in the 1956-57 season when Shaw broke his leg in the fourth game. The Colts tapped Unitas, and never looked back. His first game was not easy, however. Unitas threw his first pass for an interception. For the rest of the season, he had a pass completion percentage of 55.6. Beginning on December 9, 1956, through December 4, 1960, Unitas completed a minimum of one touchdown pass in every game he played. He began a similar streak in 1957 when he led the NFL in touchdown passes and passing yardage.

By 1958, Unitas was recognized as the best quarterback in the NFL. He was known for his ability to work well under pressure as well as for his accuracy, signal calling, and passing. To Unitas, the game was simple. He told Tex Maule in The Fireside Book of Football, "You have to gamble or die in this league. I don't know if you can call something controlled gambling, but that's how I look at my play calling. I'm a little guy, comparatively, that's why I gamble. It doesn't give those giants a chance to bury me." Unitas was known for his ferociousness on the field. Merlin Olsen, who played against him for the Los Angeles Rams, told Paul Zimmerman of Sports Illustrated, "I often heard that sometimes he'd hold the ball one count longer than he had to just so he could take the hit and laugh in your face."

In 1958, the Colts made it to the NFL's championship game against the New York Giants. Unitas had to play injured, as he often did throughout his career. He had three broken ribs, and his protective gear weighed nine pounds. The Giants led towards the end of the game, 17-14 but Unitas got his team back into the game by completing seven passes in under 90 seconds so they could tie the score with a field goal before the end of regulation. A new league rule dictated that the game go into overtime. Previously all games, even those deciding a championship, could end with a tie. In overtime, Unitas led the Colts to victory by using unexpected plays to set up a touchdown in an 80-yard drive. The final score was Colts 23, Giants 17. It marked the Colts first championship.

The victory was spectacular. Many consider it to be the greatest game ever played in the NFL. Unitas was named the championship's most valuable player (MVP). Over 50 million fans watched the game. While it made Unitas a household name, he also believed it made professional football more widely known. Unitas told Dianne C. Witter of Arthritis Today, "Television was just catching on at the time. So that game was the first nationally televised pro football championship game. It was watched by more spectators than any other sporting event in the world up until that time. That game was the one that pushed the NFL into the prominence it has in America right now."

In the 1958-59 season, Unitas continued to dominate. He led the league in passing yardage and completions. He was named the league's most valuable player, winning the Bert Bell Award. In the season's championship game, the Colts again beat the Giants. This time the victory was more decisive, 31-16, and Unitas again was the championship's MVP. After this season, however, the Colts were not a great team for several years. Despite this, Unitas shined. During the 1959-60 season, for example, he led the NFL in passing yardage and completions. By 1962-63, the team had improved, and Unitas again led the NFL in passing yardage and completions. In 1963-64, his effort was rewarded with the Bell Trophy. While the Colts went on to win their conference championship, they lost to the Cleveland Browns in the NFL championship.

The late 1960s featured many of Unitas's last moments of greatness. In the 1965-66 season, he broke the NFL's season records for most passes thrown for touchdowns and most yards gained. The following season, Unitas won the Bell Trophy, and again led the NFL in completion percentage. He suffered a setback in the 1967-68 season when he tore a muscle in his right elbow, missing most of the season. The Colts went on to win the NFL championship in 1968 without him. Unitas returned the following season, to lead the Colts to Superbowl III. But he did not play because of torn ligaments in his throwing arm. The team lost to the New York Jets, 16-7. Despite such losses, Unitas continued to receive accolades. In 1969, the NFL's 50th anniversary, he was named the Greatest Quarterback of All Time. He was also named Associated Press Player of the Decade for the 1960s.

Unitas had his last great season in 1969-70. He was named the NFL's Man of the Year for completing 166 of his 221 pass attempts, for 2213 yards and 14 touchdowns. But Unitas also threw 18 interceptions. The Colts returned to the Super Bowl against the Dallas Cowboys. Unitas only played in the first quarter and a half because he suffered a bruised rib in the second quarter. Injury problems would plague him for the rest of his career. In 1971, Unitas began having arm problems. He tore his Achilles tendon in April 1971 while playing paddleball, which might have been the beginning of the end. Despite this, the Colts won the NFL championship in 1971. Unitas's difficulties extended off the field as well. He and his first wife divorced. Unitas was later remarried to Sandra, with whom he had another son, Francis Joseph.

Unitas played his last game as a Colt on December 3, 1972, after which he was benched and traded to the San Diego Chargers. There, Unitas was the backup quarterback. He retired at the end of the 1973 season, after 18 years in the NFL. Unitas only retired when he could no longer play. He told Dianne C. Witter of Arthritis Today, "When it's time to quit, it's time to quit." Unitas's career statistics were impressive. He threw 5186 passes, completing 2830, a percentage of over 55%. These passes were for 40,239 yards, at the time a NFL record. Unitas held other NFL records when he retired: most seasons passing for more than 3000 yards, (3); most games passing for 300 yards or more, (27); most touchdowns thrown, (290). He also held two post-season records: highest pass completion percentage, (62.9%); and most yards gained passing during championship play, (1177).

Even before Unitas retired, he already had business interests. After retirement, he went into the restaurant business. He had a restaurant in Baltimore called The Golden Arm, which he sold in 1988. Unitas had business interests in central Florida as well, including a restaurant and real estate. Unitas also worked as a representative for several manufacturing companies and was a trucking company's spokesman. He did not forget football, nor did the game for get him. In 1974, he became a commentator for CBS, and was known for his honesty during his five-year tenure in the broadcast booth. In 1979, Unitas was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Unitas became a subject of controversy in the mid-1980s. He used his celebrity status to endorse many projects. One of them was a second mortgage company, First Fidelity Financial Services, Inc., of Hollywood, Florida. The company went bankrupt and its founder was convicted of fraud. Unitas was sued for endorsing a bad product. By 1998, he presided over two companies that bore his name. He was the chair of a sports management company named Unitas Management Corp. and gave out scholarships through Johnny Unitas Golden Arm Educational Foundation. He also worked as vice president of sales for a computer electronics firm, National Circuits, which he had bought with a partner in 1984.

But it was football that defined the Unitas legacy. Of his career, Paul Zimmerman of Sports Illustrated, wrote "He was the antithesis of the highly drafted, highly publicized young quarterback. He developed a swagger, a willingness to gamble. He showed that anyone with basic skills could beat the odds if he wanted to succeed badly enough and was willing to work."