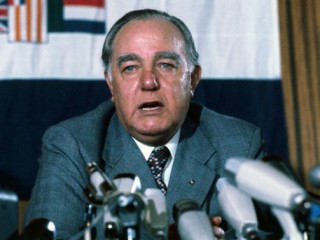

John Vorster biography

Date of birth : 1915-04-11

Date of death : 1983-09-10

Birthplace : Jamestown, South Africa

Nationality : South African

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-01-03

Credited as : Politician and attorney, former Prime Minister of South Africa,

Balthazar Johannes Vorster, better known as John Voster was a South African political leader who emerged as a major figure in Afrikaner nationalism. Noted as a right-wing figure, he was passionately hostile to liberalism and communism.

Balthazar Vorster was born on April 11, 1915, in the rural area of Jamestown in the Eastern Province. He attended school there and subsequently entered Stellenbosch University as a law student. Stellenbosch University can be called the "cradle of Afrikaner nationalism." Its influence on the development of Afrikaans culture has been profound: no fewer than six out of the seven prime ministers South Africa had between 1910 and 1971 are former Stellenbosch men. Vorster soon involved himself in student politics. In time he became chairman of the debating society, deputy chairman of the student council and leader of the junior National party.

Vorster graduated in 1938 and became registrar (judge's clerk) to the judge president of the Cape Provincial Division of the South African Supreme Court. But he did not remain in this post for long, entering practice as an attorney in Port Elizabeth and then in the Witwatersrand town of Brakpan.

The outbreak of war in September 1939 saw Vorster's first serious involvement in national politics. The decision of the South African Parliament to enter war on the side of the Allied Powers bitterly alienated Afrikaner nationalists, who resented South Africa's alliance with their ancient foe, England. Many nationalists, more out of an anti-English feeling than a positively pro-Nazi spirit, fervently hoped for a German victory.

Vorster channeled his activities into an organization called the Ossewabrandwag (literally, "Ox-wagon Sentinel"), which had been founded in 1938 to perpetuate the spirit engendered by the celebration in that year of the centenary of the Great Trek. Under the führer-type leadership of J. F. van Rensburg, the Ossewabrandwag became an extremist neo-Nazi organization that did its best to hamstring the South African war effort. Although Vorster himself claimed not to have participated, many acts of sabotage and violence committed in the country during the war were attributed to the Ossewabrandwag.

Rising rapidly in the organization, which was run on paramilitary lines, Vorster reached the rank of general. In one statement made in those times he identified himself with "Christian Nationalism," which he described as the South African equivalent to National Socialism. Vorster's brother, J. D. Vorster, a Dutch Reformed Church clergyman, also leaned heavily to the German side, receiving a prison sentence for conveying information about Allied shipping movements to the enemy.

In September 1942, Vorster was interned in a detention camp at Koffiefontein, Cape, because of his activities. He repeatedly demanded that he be brought before a court of law, and he even led a hunger strike in an attempt to pressure the authorities to charge or release him. He remained an internee until February 1944, when he was released and placed under restrictions. He refused to obey these restrictions, which included confinement to a particular district, but he was not punished or reinterned for doing so.

In later years when Vorster had become an important figure in the National party, his opponents taunted him with his wartime activities. Vorster never tried to disavow anything he did or said at that time. He described his internment in a speech in Parliament in May 1960, saying that one possible reason had been that he was believed by the authorities to have harbored antiwar fugitives. He described also how, on being released, he had called on the minister of justice, Colin Steyn, to plead on behalf of those who were still interned. Steyn, he said, threatened to have him arrested unless he left the building immediately. The experience of internment had an embittering, searing effect on Vorster and increased his extremism.

Relations between the Ossewabrandwag and the National party, led by Daniel Malan, reached breaking point by the end of 1941. Having been repudiated by the Nationalists, the Ossewabrandwag subsequently entered into alliance with the Afrikaner party, which was formed in 1941. The next important stage in Vorster's political career came in 1948, when he sought to gain nomination as the Afrikaner party candidate for Brakpan in the elections of that year. Relations between the National and Afrikaner parties had been sufficiently restored to enable them to enter an electoral pact against Jan Smuts's United party, which was then in power. The Nationalists, however, mistrusted the young firebrand Vorster and refused to endorse his candidacy. He stood as an independent only to be defeated by the narrowest of margins—four votes. Vorster had to wait until the 1953 election to enter parliament, which he did as the Nationalist member of the Transvaal constituency of Nigel.

Vorster soon proved himself to be a very able parliamentarian, a good debater, highly skilled at political infighting and popular as a speaker at Nationalist party meetings. His rise in the party hierarchy was rapid. He was made deputy minister of education, arts and science in 1958, and in 1961 he was made a full minister and given the important portfolio of justice, as well as that of social welfare and pensions.

In 1961 South Africa was still under the pall of Sharpeville (the killing of 83 demonstrating Africans by police fire in March 1960). Both the major African political organizations, the African National Congress and the Pan-African Congress, had been proscribed, but the possibility of internal insurrection was real as various underground organizations committed to violence were formed. Vorster's response was to arm himself, as minister of justice, with extraordinary powers to deal with extra parliamentary opposition.

Under Vorster's aegis the security police became a formidable machine, penetrating every nook and cranny of society, ferreting out opponents, and exposing underground movements. Draconian security legislation was passed, giving the authorities, in effect, carte blanche to do what they liked, with little or no possibility of being curbed by the courts. Detention without trial, initiated as a temporary measure, became a permanent part of the South African scene and was used extensively against persons suspected of unlawful political activity.

Vorster's vigorous and, from the Nationalists' point of view, highly successful handling of the security situation greatly enhanced his prestige in his party. He could claim to be the "strong man" who had smashed internal resistance movements and made the country secure. Moreover, his controversial activities as minister of justice had ensured him of a constant place in the political limelight. It was little surprise, then, when after the assassination of Hendrik Verwoerd in September 1966, Vorster was unanimously elected leader of the National party and became prime minister.

As prime minister Vorster cultivated a more "moderate" image, going out of his way to attract English-speaking whites and assiduously trying to win the friendship of black African states. Both of these aspects of his policy aroused the ire of the extreme right wing of the party, the Verkramptes, who were grouped around a Cabinet minister, Albert Hertzog. Vorster moved very gingerly in the face of growing Verkrampte criticism: he did not wish to go down in history as the leader who had allowed Afrikaner nationalism to lose its hard-won unity.

For two stormy years, from 1967 until late in 1969, Vorster attempted to hold the party together, but finally his patience and that of his key lieutenants was exhausted, and the Verkramptes (including four Nationalist members of Parliament) were flushed out of the party. In a snap election held in April 1970, the Reconstituted National party (as the Verkramptes called the party they formed) was thoroughly trounced.

Despite this apparent vindication, it was clear that Vorster's control of Nationalist Afrikanerdom was by no means as complete as Verwoerd's had been. For one thing, he was no intellectual, and this was a serious disadvantage for a party whose apartheid policies were manifestly failing. For another, Afrikanerdom has become more diversified, more pluralist, and consequently the sources of internal conflict have become greater.

Vorster served briefly in the largely ceremonial position of president (1978-79) and died Sept. 10, 1983.

There is neither a biography of Vorster nor a work which deals exclusively with his activities as minister of justice or prime minister. His parliamentary speeches may be read in the verbatim reports of the House of Assembly Debates. Recommended for general historical background are Leopold Marquard, The Peoples and Policies of South Africa (1952; 4th ed. 1969), and Margaret Livingstone Hodgson Ballinger, From Union to Apartheid: A Trek to Isolation (1969).