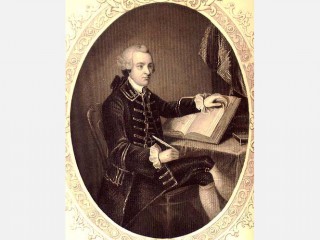

John Hancock biography

Date of birth : 1737-01-23

Date of death : 1793-10-08

Birthplace : Braintree, Massachusetts

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-09-30

Credited as : Politician and governor, statesman,

9 votes so far

Early life

John Hancock was born in Braintree, Massachusetts, on January 23, 1737. His parents were John Hancock, a Harvard graduate and minister, and Mary Hawke. After the death of his father when Hancock was seven, he was adopted by his uncle, a wealthy Boston merchant. Hancock graduated from Harvard in 1754, served for a time in his uncle's office as a clerk, and went to London in 1760 as the firm's representative. He spent a year there. In 1763 Hancock became a partner in his uncle's thriving business.

When his uncle died in 1764, Hancock inherited the business. He was one of many who was opposed to Great Britain's passing of the Stamp Act in 1765, since the act taxed the kinds of transactions, or business dealings, his company was involved with. As a result, to avoid having to pay these taxes, Hancock ignored the law and began smuggling (bringing in secretly) goods into the colonies.

Hancock was elected to the Massachusetts General Court in 1766 at the suggestion of other colonists who were against British interference in the colonies. Hancock had attracted attention as something of a hero after one of his smuggling ships, the Liberty, was seized by the British. He received more votes than Samuel Adams (1722–1803), one of the most famous American Revolutionary leaders, in the next General Court election. Meanwhile, Hancock was threatened with large fines by Britain for the Liberty affair. Though the fines were never collected, Hancock never got his ship back.

Growing anti-British sentiment

Every time the British made a move that affected the American colonies, especially anything involving taxes, Samuel Adams and other anti-British agitators (people who stir up public feeling on political issues) spoke out against it. The Boston Massacre of 1770 (when British soldiers fired into a crowd of people who had been throwing snowballs and sticks at them, killing five) increased colonial anger toward Britain and established a tension that continued to grow. Hancock wavered for a time, but when the strength of public opinion became clear, he made the courageous announcement that he was totally committed to making a stand against the actions of the British government—even if it cost him his life and his fortune.

During the Boston Tea Party of 1773, Boston colonists disguised as Native Americans dumped three shiploads of British tea into the harbor as a protest against the British government. After the Boston Tea Party, the British passed the Boston Port Bill of 1774. The bill ordered the closing of the port of Boston until the cost of the tea was repaid. Hancock's reputation grew during this time to the point where he became one of the main symbols of anti-British radicalism (extreme actions trying to force change). How much of this was planned by him, and how far he had been pushed by Samuel Adams, is uncertain. What is known is that when British General Thomas Gage finally decided to try to achieve peaceful relations with the colonies, Hancock and Adams were the only two Americans to whom he refused to even consider giving amnesty (a pardon).

Continental Congress

Hancock was elected president of the Continental Congress in May 1775 and married Dorothy Quincy in August of the same year. He hoped to be named to command the army around Boston and was disappointed when George Washington (1732–1799) was selected instead. Hancock voted for, and was the first representative to sign, the Declaration of Independence. Although Hancock resigned as president of the Continental Congress in October 1777, saying that he was in poor health, he stayed on as a member.

Hancock still wanted to prove himself as a military leader. However, when given the opportunity to command an expedition into Rhode Island in 1778, he did nothing to distinguish himself. Hancock was also embarrassed in 1777 when Harvard College, which he had served as treasurer since 1773, accused him of mismanaging university funds and demanded repayment. Hancock was forced to pay £16,000 (approximately $22,000). In 1785 Hancock admitted that he still owed £1,054 (approximately $1,500) to Harvard. This sum was eventually paid out of his estate after his death.

Elected to office

Like most public figures, Hancock had enemies. His opponents spread the word that he was a shallow man who lacked strong beliefs and was only interested in helping himself. Nevertheless, they could not prevent his election as the first governor of Massachusetts, in 1780. He was reelected several times until retiring in 1785 just before Massachusetts went through a financial crisis. Although he claimed that his retirement was based on illness, Hancock's enemies claimed that he had seen the coming storm, which was caused in part by mistakes he had made in handling the state's money. After Shays's Rebellion (a 1786–87 uprising by farmers and small property owners in Massachusetts who demanded lower taxes, court reforms, and a revision of the state constitution), Hancock was reelected governor.

In 1788, Hancock was elected president of the Massachusetts State Convention to ratify, or approve, the new Constitution. He was approached by members of the Federalist Party (an early political group that supported a strong central government) who wanted a set of amendments added to the document. They supposedly hinted that if Hancock presented the amendments, they would help him to be named president if Washington declined the job. The truth of this story has never been confirmed. In the end, Hancock did offer the amendments, and Massachusetts ratified the Constitution. Washington accepted the presidency, and Hancock remained as Massachusetts governor, his popularity unchallenged. He died in office on October 8, 1793.