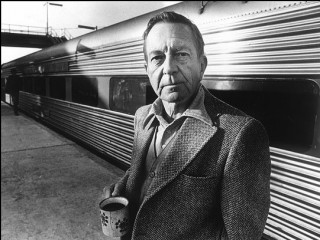

John Cheever biography

Date of birth : 1912-05-27

Date of death : 1982-06-18

Birthplace : Quincy, Massachusetts, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-08-19

Credited as : Novelist and writer of short stories, won the Pulitzer Prize, created "Cheever People"

1 votes so far

John Cheever is among the finest American writers of the twentieth century. His stories chronicle the spiritual shortcomings of upper-class suburbia while maintaining an optimistic outlook and a sense of humor. Robert A. Morace, writing in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, explained that "his characters all face a similar problem: how to live in a world which, in spite of its middle-class comforts and assurances, suddenly appears inhospitable, even dangerous." A reformed alcoholic who lived in the suburbs himself, Cheever, eulogized Peter S. Prescott in Newsweek, "that in a world that most people envy there are people who are bravely enduring." Among Cheever's awards were the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Cheever was born May 27, 1912, in Quincy, Massachusetts, the second son of Frederick Lincoln and Mary Liley Cheever. His father owned a shoe factory in nearby Lynn, but he lost the business during the Great Depression. His mother was able to support the family by creating her own businesses: a tea room and a gift shop. Frederick Cheever, his pride shattered, greatly resented his wife's independence, eventually turning to alcohol and attempting suicide. The strain took its toll on all of the family members; both John and his older brother, Fred, became alcoholics, as well.

Cheever displayed a gift for storytelling at a young age, earning a reputation at his elementary school for creating entertaining, improvised tales. "Many of the characters in those storytelling exercises--eccentric old women, ship captains, orphan boys--later became standard figures in his stories and novels," according to Patrick Meanor, writing in the Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives. Cheever's grandmother, Sarah Liley, encouraged his talents, reading to him from the works of Jack London, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Charles Dickens.

Despite his love of reading and writing, Cheever was not a particularly distinguished student. He enrolled at Thayer Academy, a prep school in South Braintree, Massachusetts, dropping out in his junior year to attend Quincy High School. For senior year in 1929 he returned to Thayer Academy, but he was expelled. Cheever "variously claimed that he was caught smoking, that it was his poor grades, and that he had seduced the son of one of the teachers," remarked Meanor. "However, it was not unusual for Cheever to come up with divergent explanations for events in his early life. Certainly his casual treatment of facts about his life demonstrates the greater importance he placed on creativity and highlight his ability to entertain the fictive possibilities of a situation or character."

Cheever's long career as a short story writer began in 1930 when he sold his first story, "Expelled," to the New Republic. "Although Cheever ... referred to the story slightingly as 'the reminiscences of a sorehead,' his story is neither plaintive nor amateurish and in many ways anticipates the style that has since become Cheever's hallmark," noted Robert A. Morace in the Dictionary of Literary Biography. Morace added, "Thematically, 'Expelled' also anticipates Cheever's later work. There is the conflict between the decorum required by the school and the fervent longing for life felt by the individual."

Begins Writing Career

After leaving Thayer, Cheever toured Europe with his brother. He settled in Boston for a time, working in department stores and freelancing for a number of Boston newspapers. In the mid-1930s Cheever moved to New York City, living in a squalid boarding house in Greenwich Village and supporting himself by writing synopses of books for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. He met some influential members of the literary set, including John dos Passos, e. e. cummings, James Agee, Paul Goodman, and James Farrell. Malcolm Cowley, the editor of the New Republic, helped arrange visits to the Yaddo writers' colony at Saratoga Springs, New York. During this time, Cheever also began his long association with the New Yorker.

Cheever became a regular contributor to the New Yorker in 1934, a relationship that would last for decades and account for the publication of a majority of his stories. His short work, at times discounted because it was categorized as New Yorker style, earned a wider audience and greater recognition when his collection The Stories of John Cheever was not only awarded the Pulitzer Prize in fiction in 1979, but also the National Book Award for fiction in 1981. The publication of this volume of sixty-one stories, including such titles as "The Enormous Radio," "The Country Husband," "The Chimera," and "The Swimmer," "revived singlehanded publishers 'and readers' interest in the American short story," according to Time's Paul Gray. Commenting on the author's place in American literature, John Leonard wrote in the Atlantic Monthly at the time: "I happen to believe that John Cheever is our best living writer of short stories: a[n Anton] Chekhov of the exurbs."

A Cynical View of Suburbia

Cheever the novelist was not as widely praised, but even in this role he had his champions. In 1977, fellow author John Gardner maintained that "Cheever is one of the few living American novelists who might qualify as true artists. His work ranges from competent to awesome on all the grounds I would count: formal and technical mastery; educated intelligence; what I would call 'artistic sincerity' ...; and last, validity." His novels--most notably The Wapshot Chronicle, Bullet Park, and Falconer--display "a remarkable sensitivity and a grimly humorous assessment of human behavior that capture[s] the anguish of modern man," commented Robert D. Spector in World Literature Today, "as much imprisoned by his mind as by the conventions of society."

Cheever drew on the same confined milieu--geographical and social--in creating his five novels and numerous stories. "There is by now a recognizable landscape that can be called Cheever country," Walter Clemons observed in Newsweek. It comprises "the rich suburban communities of Westchester and Connecticut," explained Richard Locke in the New York Times Book Review, "the towns [the author] calls Shady Hill, St. Botolphs and Bullet Park." In this country Cheever found the source for his fiction, the lives of upwardly mobile Americans, both urban and suburban, lives lacking purpose and direction. His fictional representation of these lives capture what a Time reviewer termed the "social perceptions that seem superficial but somehow manage to reveal (and devastate or exalt) the subjects of his suburban scrutiny." Fashioned from the author's observations and presented in this manner, Cheever's stories have become, in the opinion of Jesse Kornbluth, "a precise dissection of the ascending middle class and the declining American aristocracy."

Creates "Cheever People"

For the most part, the characters represented in Cheever's short stories and novels are white and Protestant; they are bored with their jobs, trapped in their lifestyles, and out of touch with their families. "Cheever's account of life in suburbia makes one's soul ache," Guy Davenport remarked in National Review. Added the reviewer: "Here is human energy that once pushed plows and stormed the walls of Jerusalem ... spent daily in getting up hung over, staggering drugged with tranquilizers to wait for a train to ... Manhattan. There eight hours are given to the writing of advertisements about halitosis and mouthwash. Then the train back, a cocktail party, and drunk to bed." According to Richard Boeth of Newsweek, "what is missing in these people is not the virtue of their forebears ... but the passion, zest, originality and underlying stoicism that fueled the Wasps' domination of the world for two ... centuries. Now they're fat and bored and scared and whiny."

A recurring theme in Cheever's work is nostalgia, "the particular melancholia induced by long absence from one's country or home," Joan Didion explained in the New York Times Book Review. In her estimation, Cheever's characters have "yearned always after some abstraction symbolized by the word 'home,' after 'tenderness,' after 'gentleness,' after remembered houses where the fires were laid and the silver was polished and everything could be 'decent' and 'radiant' and 'clean.'" Even so, Didion added, "such houses were hard to find in prime condition. To approach one was to hear the quarreling inside.... There was some gap between what these Cheever people searching for home had been led to expect and what they got." What they got, the critic elaborated, was the world of the suburbs, where "jobs and children got lost." As Locke put it, Cheever's character's nostalgia grows out of "their excruciating experience of present incivility, loneliness and moral disarray."

Throughout his tales of despair and nostalgia, Cheever offers an optimistic vision of hope and salvation. His main characters struggle to establish an identity and a set of values "in relation to an essentially meaningless--even absurd--world," Stephen C. Moore commented in the Western Humanities Review. Kornbluth found that "Cheever's stories and early novels are not really about people scrapping for social position and money, but about people rising toward grace." In his Dictionary of Literary Biography essay, Robert A. Morace came to a similar conclusion. Morace maintained that "while he clearly recognizes those aspects of modern life which might lead to pessimism, his comic vision remains basically optimistic.... Many of his characters go down to defeat, usually by their own hand. Those who survive ... discover the personal and social virtues of compromise. Having learned of their own and their world's limitations, they can, paradoxically, learn to celebrate the wonder and possibility of life."

New Yorker Style Not Suitable for Novels

Critics have also been impressed by Cheever's episodic style. In a review of Bullet Park, a Time critic notes that most of the novel "is composed of Cheever's customary skillful vignettes in which apparent slickness masks real feeling." Some reviewers did find, however, that although this episodic structure works well in Cheever's short fiction, his novels "flounder under the weight of too many capricious, inspired, zany images," as Joyce Carol Oates remarked in the Ontario Review. John Updike once offered a similar appraisal: "In the coining of images and incidents, John Cheever has no peer among contemporary American fiction writers. His short stories dance, skid, twirl, and soar on the strength of his abundant invention; his novels fly apart under its impact." Moreover, Oates contended that though "there are certainly a number of powerful passages in Falconer, as in Bullet Park and the Wapshot novels, ... in general the whimsical impulse undercuts and to some extent damages the more serious intentions of the works." Of the "Wapshot" novels, The Wapshot Chronicle received the National Book Award in 1958.

Clemons, among others, drew a different conclusion. He noted that "the accusation that Cheever 'is not a novelist' persists," despite the prestigious awards, such as the Howells Medal and the National Book Award, his novels have received. Clemons suggested that this lack of reviewer appreciation was due to Cheever's long affiliation with the New Yorker. "The recognition of Cheever's [work] has ... been hindered by its steady appearance in a debonair magazine that is believed to publish something familiarly called 'the New Yorker story,'" he wrote, "and we think we know what that is." Clemons added: "Randall Jarrell once usefully [defined the novel] as prose fiction of some length that has something wrong with it. What is clearly 'wrong' with Cheever's ... novels is that they contain separable stretches of exhilarating narrative that might easily have been published as stories. They are loosely knit. But so what?"

On the whole, the critical and popular response to Cheever's work has remained favorable. Although some have argued that his characters are unimportant and peripheral and that the problems and crises experienced by the upper middle class are trivial, others, such as Time reviewer Gray, contended that the "fortunate few [who inhabit Cheever's fiction] are much more significant than critics seeking raw social realism will admit." Gray explained: "Well outside the mainstream, the Cheever people nonetheless reflect it admirably. What they do with themselves is what millions upon millions would do, given enough money and time. And their creator is less interested in his characters as rounded individuals than in the awful, comic and occasionally joyous ways they bungle their opportunities." John Leonard of the New York Times found the same merits, concluding that "by writing about any of us, Mr. Cheever writes about all of us, our ethical concerns and our failures of nerve, our experience of the discrepancies and our shred of honor."

Journals Expose Private Side

In 1991 Cheever's son Benjamin published an edited version of Cheever's journals. Written over a period of thirty-five years, and comprising twenty-nine looseleaf notebooks when unedited, the journals were distilled to a hefty 399-page book by Robert Gottlieb titled The Journals of John Cheever. The book is marked by Cheever's woeful reminiscences about life, in particular his addiction to alcohol and his growing dissatisfaction with his marriage.

Cheever's alcoholism grew slowly. He began as a social drinker during the 1950s, and over the years progressed to a full-blown alcoholic. In 1975 he checked himself into a rehabilitation clinic and managed to end his addiction. Unlike many other authors, he was able to continue writing successfully after giving up drinking. During this same period, Cheever found much to complain about in his marriage. He found his wife angry, mean, and unsupportive, even after he gave up alcohol.

Cheever also delves into his awakening sexual identity. As a child he was considered effeminate by others, and friends and family members speculated that he might be gay. Cheever, himself, hid the fact from others and himself for many years. It was not until he had been with several male lovers that he became more open about his bisexuality.

Critical reaction to the published journals was mixed. Scott Donaldson, writing in the Chicago Tribune Books, felt that the volume is "exquisitely written" but depressing: "the story these ... journals tell is almost unrelievedly one of woe." He concludes that "troubled though the story of [his] life may be, it is told in the same luminous prose that characterized his stories and novels. He takes us on a journey to the depths, but we could not want a better guide." While Jonathan Yardley, writing in the Washington Post Book World, also characterized the writing in the book as exceptional, he pondered the need for the publication of the volume: "it is difficult to see how it contributes anything of genuine importance to our understanding of Cheever's work," Yardley noted, reflecting the view of several critics.

After Cheever's death, his widow signed a contract with small publisher Academy Chicago to publish some of his previously uncollected short stories. However, when the family realized the publisher was going to print all sixty-eight of Cheever's uncollected stories, they balked and took legal action against the publisher. After a long and expensive battle, Academy Chicago lost the right to publish all the works but was allowed to publish thirteen of the stories. Oddly, Cheever had chosen not to publish these early stories in a collection form during his lifetime because he did not believe they measured up to his later works.

The stories tread on familiar Cheever ground: the troubles of the East Coast middle class. In "His Young Wife" an older man is upset by the fact that his wife is slipping away from him. He turns to gambling as a means to ruin his rival and win back the love of his wife. "In Passing" visits Saratoga, New York, during its famed racing season. Against that capitalistic backdrop, a Marxist organizer is upset over the bank's repossession of his family house and finds himself in turmoil over his family's reaction to the tragedy. "Family Dinner" looks at the devices a husband and wife use to fool themselves and each other in an unhappy marriage. "Cheever's sympathetic feelings are liberal, generous and extensive," commented Mark Harris in the Chicago Tribune Books. "His command of his craft, on the other hand, had yet to be fully developed."

Sven Birkerts, writing in the New York Times Book Review, found that "the stories are competent, solid," yet he believed that "such a collection would not see the light if it did not have the Cheever name on the cover." John B. Breslin concluded in America: "immature some of these stories may be, but not embarrassingly so, and certainly much less 'naked' in their revelations of the writer than the letters and journals that have been published with the approval and participation of his family. [Editor] Franklin Dennis has done Cheever no disservice with this collection and has done his admirers a favor."

Cheever's name is often raised by critics alongside the names of such highly regarded contemporaries as John O'Hara, Saul Bellow, Thomas Pynchon, and Philip Roth. Yet, as Peter S. Prescott noted in a Newsweek tribute on the occasion of Cheever's death, "His prose, unmatched in complexity and precision by that of any of his contemporaries ... is simply beautiful to read, to hear in the inner ear--and it got better all the time." "More precisely than his fellow writers," added Prescott, "he observed and gave voice to the inarticulate agonies that lie just beneath the surface of ordinary lives." In the words of Gray, recorded in a Time tribute, Cheever "won fame as a chronicler of mid-century manners, but his deeper subject was always the matter of life and death."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born May 27, 1912, in Quincy, MA; died of cancer, June 18, 1982, in Ossining, NY; son of Frederick (a shoe salesman and manufacturer) and Mary (a gift shop owner; maiden name, Liley) Cheever; married Mary M. Winternitz (a poet and teacher), March 22, 1941; children: Susan, Benjamin Hale, Frederico.

AWARDS

Guggenheim fellowship, 1951; Benjamin Franklin Award, 1955, for "The Five Forty-eight"; American Academy of Arts and Letters award in literature, 1956; O. Henry Award, 1956, for "The Country Husband," and 1964, for "The Embarkment for Cythera"; National Book Award in fiction, 1958, for The Wapshot Chronicle; Howells Medal, American Academy of Arts and Letters, 1965, for The Wapshot Scandal; Editorial Award, Playboy, 1969, for "The Yellow Room"; honorary doctorate, Harvard University, 1978; Edward MacDowell Medal, MacDowell Colony, 1979, for outstanding contributions to the arts; Pulitzer Prize in Fiction, 1979, National Book Critics Circle Award in Fiction, 1979, and National Book Award in Fiction, 1981, all for The Stories of John Cheever; National Medal for Literature, 1982.

CAREER

Novelist and short story writer. Instructor at Barnard College, 1956-57, Ossining, NY, Correctional Facility, 1971-72, and at University of Iowa Writers Workshop, 1973; visiting professor of creative writing, Boston University, 1974-75. Member of cultural exchange program to U.S.S.R., 1964.

WORKS

* NOVELS

* The Wapshot Chronicle (also see below), Harper (New York, NY), 1957.

* The Wapshot Scandal (also see below), Harper (New York, NY), 1964.

* Bullet Park, Knopf (New York, NY), 1969.

* Falconer, Knopf (New York, NY), 1977.

* The Wapshot Chronicle [and] The Wapshot Scandal, Harper (New York, NY), 1979.

* Oh, What a Paradise It Seems, Knopf (New York, NY), 1982.

* SHORT STORIES

* The Way Some People Live: A Book of Stories, Random House (New York, NY), 1943.

* The Enormous Radio and Other Stories, Funk (New York, NY), 1953.

* (With others) Stories, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1956, published as A Book of Stories, Gollancz (London, England), 1957.

* The Housebreaker of Shady Hill and Other Stories, Harper (New York, NY), 1958.

* Some People, Places, and Things That Will Not Appear in My Next Novel, Harper (New York, NY), 1961.

* The Brigadier and the Golf Widow, Harper (New York, NY), 1964.

* Homage to Shakespeare, Country Squire Books (Stevenson, CT), 1965.

* The World of Apples, Knopf (New York, NY), 1973.

* The Day the Pig Fell into the Well (originally published in the New Yorker), Lord John Press (Northridge, CA), 1978.

* The Stories of John Cheever, Knopf (New York, NY), 1978.

* The Leaves, the Lion-Fish and the Bear, Sylvester and Orphanos (Los Angeles, CA), 1980.

* Angel of the Bridge, Redpath Press (Minneapolis, MN), 1987.

* Thirteen Uncollected Stories, Academy Chicago Publishers (Chicago, IL), 1994.

* The Stories of John Cheever, Vintage International (New York, NY), 2000.

* OTHER

* The Letters of John Cheever, edited by Benjamin Cheever, Simon & Schuster (New York, NY), 1988.

* The Journals of John Cheever, Knopf (New York, NY), 1991.

* (With John D. Weaver) Glad Tidings: A Friendship in Letters, HarperCollins (New York, NY), 1993.

* Vintage Cheever, Vintage Books (New York, NY), 2005.

* Also author of television scripts, including Life with Father. Contributor to numerous anthologies, including O. Henry Prize Stories, 1941, 1951, 1956, 1964. Contributor to periodicals, including New Yorker, Collier's, Story, Yale Review, New Republic, Atlantic Monthly, and other publications.