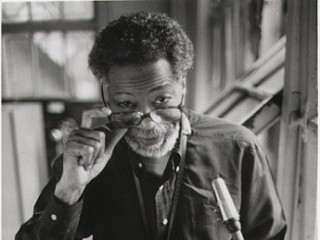

Joe Henderson biography

Date of birth : 1937-04-24

Date of death : 2001-06-30

Birthplace : Lima, Ohio, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-11-29

Credited as : jazz tenor, saxophonist, "Professor Emeritus at interpretation"

1 votes so far

A lasting figure on the jazz scene, tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson has quietly pursued his craft with a learned passion. A central contributor to the classic Blue Note sessions of the 1960s and a composer, bandleader, and educator through the 1970s and 1980s, he stepped out of the shadows of the industry's saxophone giants in the early 1990s, recording tributes to jazz greats Billy Strayhorn and Miles Davis. Fame finally caught up with Henderson in 1992, when his career was properly reevaluated in light of the Strayhorn disc.

The broad-minded Henderson views his performing in terms of the other creative arts. "I think of music on the bandstand like an actor relates to a role," he told Michael Bourne in a 1992 interview for Down Beat. "I've always wanted to be the best interpreter the world has ever seen.... The creative faculties are the same whether you're a musician, a writer, a painter. I can appreciate a painter as if he were a musician playing a phrase with a stroke, the way he'll match two colors together the same as I'll match two tones together." Henderson's synthesis of script and improvisation, of tradition and originality, epitomizes the fresh and distinctive power of great jazz art.

Born April 24, 1937, in Lima, Ohio, Henderson was one of 15 children. The range of musical taste in his family was wide; he heard one sister's opera records, another sister's Bo Diddley, and country and western on the radio. "I happened to have grown up listening to [country music legend] Johnny Cash ... as much as I did [innovative jazz saxophonist] Charlie Parker," he told Lee Hildebrand of Request. One of Henderson's brothers was addicted to the noted ensemble Jazz at the Philharmonic, and Henderson was thus listening to horn players Lester Young and Ben Webster at the ripe age of six--though the sax wasn't his first love. "I wanted to play drums," he explained to Bourne. "I'd be making drums out of my mother's pie pans." When Henderson was nine, his schoolteachers tested his musical abilities. "They said I'd gotten a high enough score that I could play anything, and they gave me a saxophone." He bought his first horn with money from a paper route.

Henderson's musical appreciation and exploration continued in high school, where he listened to classical composers and pianists. "I started playing in high school bands, which didn't play bebop," he revealed to Mark Gilbert in Jazz Journal International. Instead he trained on marches and classical music. He was prepared for the atonal, free-jazz experiments of 1960s figures like Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy by listening to the works of Russian-American composer Igor Stravinsky and Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg. Henderson also befriended pianists in Lima, who introduced him to a range of classical piano compositions and bebop. When he was 14, he subbed for an ailing saxophonist in the Lionel Hampton Band as the group passed through town. At the same age, he traveled to a dance in Detroit and there met the immortal Charlie Parker.

Henderson attended Kentucky State University in 1955 and transferred to Detroit's Wayne State University the following year. In the four years he studied there, Detroit was a fertile city for jazz. Henderson's classmates at Wayne State included Yusef Lateef and Curtis Fuller, and he spent evenings playing with Barry Harris, Pepper Adams, Donald Byrd, and Sonny Stitt. He also met John Coltrane during this time; in 1960 Coltrane recommended Henderson as a replacement for the Miles Davis Quintet. The U.S. government beckoned, however, and Henderson was drafted. He spent two years in the U.S. Army playing with a vaudeville group called the "Rolling Along Show"--performing everywhere from the Aleutian Islands to Japan to Paris.

Discharged from the army in 1962, Henderson settled in New York City and began a stellar span of session work and public gigging--often with his peers from Michigan. During his early days in New York, he played with Brother Jack McDuff, an organist whose bluesy jazz recalled occasional work Henderson found in Detroit. He next met trumpeter Kenny Dorham and formed a band that put out Dorham's Una Mas on Blue Note in 1963. Henderson's first recording as a leader-- Page One--soon followed, and he was well on his way to becoming a staple member of the Blue Note roster during its peak years.

Backing the experiments of pianist Andrew Hill, the juke and funk of pianist Horace Silver, or the cool trumpet of Lee Morgan, Henderson adapted to the diverse talents of the Blue Note crew. He joined Silver's band in 1964 and toured extensively with them for two years. In 1965 he recorded with Hill, and three years later--paired with Wayne Shorter on sax and an ever-shifting rhythm section--he finally got his chance to play with Miles Davis. But the arrangement lasted only a few months.

All the while, Henderson was leading his own band, which recorded five albums for Blue Note. In the middle to late 1960s, he was also composing charts for a big band he and Dorham had created; the band met weekly during certain stretches and featured such artists as Pepper Adams, Chick Corea, Ron Carter, Curtis Fuller, and Michael and Randy Brecker.

In 1967 Henderson left Blue Note for Milestone Records. Then, in an unexpected move, he joined the successful pop/rock group Blood, Sweat and Tears for a brief sojourn in 1969. BS&T sought credibility through Henderson; he told Ray Townley in a 1975 Down Beat piece: "I was sort of three-in-one oil for them: I was black, I had a rep as an improvising musician, and there were soul possibilities there." But what might have been a lucrative step for Henderson simply fizzled after four months, as the band fell into disarray.

Henderson's work from the late 1960s and early 1970s revealed his increasing sense of social consciousness. "I got politically involved in a musical way," he commented to Bourne. "Especially in the '60s, when people were trying to affect a cure for the ills that have beset this country for such a long time." He cited song titles such as 1969's "Power to the People" and 1976's "Black Narcissus" as expressions of these sentiments. This period also produced "Invitation" on 1972's In Pursuit of Blackness, an oft-performed signature piece.

In 1972 Henderson moved to San Francisco, continued performing, and also began life as a private instructor. Teaching, he told Michael Ullman of Schwann Spectrum, "is another bandstand for me"--another form of interpretation. He encourages his students to study the greats and their performances, so that each aspirant might learn to vary and alter the original. "You get so far removed from the source," he explained to Ullman, "that the solo becomes your own."

Henderson's recordings were typically varied during the 1970s but showed some signs of electrification. Black Is the Color seems rock-oriented, while The Elements features synthesizers in an avant-garde setting. He even turned to contemporary fusion for a 1975 recording date, but his crew of jazz expatriates and fusion renegades--such as George Duke and Ron Carter--were so pleased to be playing with a traditionalist that the set, according to Henderson, sounded more like bebop than electrified crossover.

Having left Milestone in the mid-1970s, Henderson free-lanced through the early 1980s--he recorded with Enja, Contemporary, and Elektra/Musician--and concentrated on his teaching. His session work turned increasingly to collaborations with trumpeter Freddie Hubbard in ensembles known as Echoes of an Era, the Griffith Park Band, and the Griffith Park Collective. In 1985 Henderson returned to Blue Note, delivering a two-volume set entitled The State of the Tenor that confidently defined his own mastery.

The sessions were Henderson's first recordings in a trio format, and they highlighted his virtuosity. An Evening with Joe Henderson, released in 1987, showed him in similar form. For the rest of the decade, he recorded live sets and seemed content with life as a musician's musician, performing at Berlin's Jazzfest in 1987, playing sideman and leader on occasional Blue Note and Red Records releases, and even touring Europe with an all-female band in 1991.

Henderson's classic and versatile approach to musicmaking complemented the early 1990s interest in neo-traditional jazz, and his Verve Records debut in 1992 changed his stature considerably. The Polygram-backed label encouraged Henderson to perform a set of covers, and he chose the work of Duke Ellington collaborator Billy Strayhorn. Henderson was fulfilling his goal of becoming "Professor Emeritus at interpretation," as he put it in Jazz Journal International. The resulting release, Lush Life, was phenomenally successful, earning Henderson a Grammy Award and Down Beat's triple crown--jazz musician of the year, top tenor saxophonist, and record of the year--among readers and critics. Previously, only Ellington had achieved this feat.

Lush Life was the best-selling jazz instrumental disc of the year. Henderson's 1993 effort, So Near, So Far (Musings for Miles), a tribute to Miles Davis, was similarly conceived. The disc covers a range of the trumpeter's songs from 1947 to 1968 and features Henderson in everything from solo to quintet settings. It was similarly successful, winning another Grammy and Down Beat's trio of awards, as well as Number One jazz record of the year honors from the Village Voice and Billboard. In 1993 Henderson was welcomed to Washington, D.C., twice--for the inaugural celebrations of President Bill Clinton and for a June White House performance. In 1995 Billboard's Jeff Levenson reported that Henderson was recording another homage album, this one for Brazilian composer Antonio Carlos Jobim, who died in December of 1994. Double Rainbow: The Music of Antonio Carlos Jobim was due to be released in March of 1995.

Amused and slightly overwhelmed by all of the attention, Henderson refused to view his early 1990s success as a "comeback." "I'm busy doing what I've been doing all the time, for over 20 years," he told Zan Stewart in Down Beat. The saxophonist did become much busier with tour dates, however, and reduced his teaching load from 20 students to five. But by recording with young musicians like Stephen Scott and Renee Rosnes, he maintained his commitment to passing on jazz tradition. That tradition has been invoked, as well, in Henderson's plans to record the big-band compositions he began with Dorham in the late 1960s. By the mid-1990s, Henderson's commitment to the jazz heritage had awarded him the wider notice he so justly deserved.

Henderson died on June 30, 2001, in San Francisco, California, of heart failure. He was 64.

Selective Works:

-Page One, Blue Note, 1963.

-Our Thing, Blue Note, 1963.

-In 'n' Out, Blue Note, 1964.

-Inner Urge, Blue Note, 1966.

-Mode for Joe, Blue Note, 1966.

-The Kicker, Milestone, 1967.

-Tetragon, Milestone, 1967.

-Power to the People, Milestone, 1969.

-If You're Not Part of the Solution, You're Part of the Problem, Milestone, 1971.

-In Pursuit of Blackness, Milestone, 1972.

-Black Is the Color, Milestone, 1973.

-Joe Henderson in Japan, Milestone, 1973.

-Multiple, Milestone, 1974.

-The Elements, Milestone, 1974.

-Canyon Lady, Milestone, 1975.

-Black Narcissus, Milestone, 1976.

-Barcelona, Enja, 1977.

-Relaxin' at Camarillo, Contemporary, 1979.

-Mirror, Mirror, MPS/Pausa, 1980.

-Griffith Park Collective: In Concert, Elektra/Musician, 1982.

-The State of the Tenor, volumes 1 and 2, Blue Note, 1985.

-An Evening with Joe Henderson, Red, 1987.

-The Best of Joe Henderson, Blue Note, 1991.

-Lush Life, Verve, 1992.

-The Standard Joe, Red, 1992.

-So Near, So Far (Musings for Miles), Verve, 1993.

-Double Rainbow: The Music of Antonio Carlos Jobim, Verve, 1995.