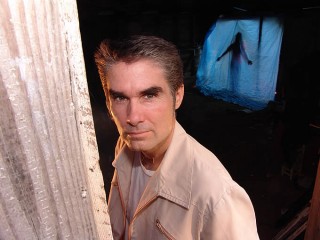

Jim White biography

Date of birth : 1957-03-10

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Pensacola, Florida,U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2012-03-13

Credited as : Singer-songwriter, Guitarist, country singer

0 votes so far

Jim White gained critical attention for his first two albums, which combined his alternative country sensibilities with surrealist observations of the American South, particularly the charismatic Pentacostalism he briefly followed in the late 1970s and early 1980s. His acerbic lyrics and dry delivery are reminiscent of the Southern Gothic literary tradition associated with Flannery O'Conner. His demonstration recordings for his first album, Wrong-Eyed Jesus, were introduced to David Byrne, former guitarist, songwriter, and singer for the band Talking Heads and a major proponent of Brazilian music on his own Luaka Bop record label. Byrne signed White, and Luaka Bop released Wrong-Eyed Jesus with a complete, O'Conner-influenced short story included in the compact disc's liner notes. His music reflects the paradox he perceives as inherent in religious faith. His songs are also noted for the sonic experimentation White and his producers employed during the recording process, resulting in haunting and moody songs that have drawn favorable comparisons to the work of Tom Waits and Victoria Williams.

White was the youngest of five children born to a couple employed by the United States military. When he was five years old, his family settled in Pensacola, Florida. His love of music began with an accident: While nursing a broken leg when he was 18 years old, he taught himself to play guitar. Before turning to religion, White was a recreational drug user in the mid- to late-1970s. Eventually, he realized, "I was lost, and when you see a trail, you follow it," he told No Depression writer Allison Stewart. "The preacher said, 'With every knee bowed and every eye closed, Jesus is calling! Accept him!' I found myself at the altar. They laid their hands on my forehead. There was something weirdly carnal about it. And I thought, well, everyone is passing out, so I better pass out, so I did. And there was lots of hugging."

After his leg healed, White began to work menial jobs, including a stint in a factory that manufactured chaise lounges. In an interview with Stewart published in No Depression, White recounted the industrial accident that resulted in serious injury to his hand: "[I] walked over to this table saw and before you could say 'boo,' they were loading me into an ambulance, three fingers on my fretting hand looking like hamburger meat." White viewed the accident as fortuitous, though: "Sometimes limitations are assets, and likewise in reverse. Before I got mangled I was a real facile guitar player, 'chord happy' I'd call it, confused and conflicted by my ability. But after I got all the pins and stitches out, and I learned how to play open chords and fret with just one finger, lo and behold, for the first time in my life what I was playing sounded right."

White continued to play and write songs, and made some home recordings. "I would play my tapes for people, which were basically stuff with a lot of different genres mixed together, jazz mixed with bluegrass, stuff like that," he told Stewart. "And they'd just go, 'Ugh, this is awful.' I always had a fragmented perspective on music. I always thought I'd be a musician by avocation, as opposed to occupation."

Still in his twenties, White relocated to New York City, at his sister's insistence, to work as a model. Before long, he was in Milan, Italy, working as a runway and photo model, earning as much as $1,000 a day. After a time, White's features and body type fell out of favor in the fashion industry, and he returned to New York City. His sister convinced him to apply to New York University, and he was accepted. While he never earned a degree, he worked on his own films, which he financed by driving a cab, and worked as a sound editor on the film Halloween 6 and entertained thoughts of becoming a professional surfer.

Plagued by chronic depression, White was again rescued by his sister in New York after his depression became severe: "I was bedridden; I thought I was an inch from death," he told Stewart. "I saw many marginal doctors, but none of them could tell me what was wrong with me. I was so depressed I could hardly think straight." He added: "There was a curse on me.... I fell into a bad river and it was carrying me away. There were crazy, spooky things happening to me."

Just as his broken leg had given him the opportunity to learn how to play guitar and his hand injury had provided the impetus to refine his guitar technique, White's mental illness helped him focus on his songwriting skills. Recovering from a debilitating nervous breakdown, his sister rented him a beach house to give him a place in which to recover. While recuperating, White wrote the song "A Perfect Day to Chase Tornadoes," the first song in the simple, personal style that he was beginning to forge.

White recorded a demonstration tape of "A Perfect Day to Chase Tornadoes," which eventually reached Melanie Ciccone, sister of Madonna, wife of performer Joe Henry, and manager of producer and performer Daniel Lanois. Ciccone sent the tape to David Byrne's Luaka Bop label. Byrne asked for a meeting with White, and signed him to Luaka Bop to record Wrong-Eyed Jesus. White enlisted help from Joe Henry, Victoria Williams, and Ralph Carney, a long-time collaborator of Tom Waits.

The album was recorded in a brief amount of time, but took ten weeks of sometimes 17-hour days to edit. The result, however, was a critical success. Writing in No Depression, critic Paige La Grone noted: "Darkly seductive like that preacher's son who smelled of sex and whiskey and spoke redemption back in high school, Jim White's debut album Wrong-Eyed Jesus beguiles the listener into riding shotgun from the git-go." Ink Blot critic Dave Rosen noted that the album "[reminds] us that hillbilly music contains themes that endure in modern times.... He writes songs that echo the strange feeling that there's something lurking beneath the surface [of] our lives that links us to the hard life of our predecessors and the art they created."

Following the album's release, White conducted a brief tour before returning to Florida to live in a mobile home, conceive a child with his partner, break up with her, and eventually reconcile. His financial and emotional situation was dire, and he wrote the song "Ten Miles to Go on a Nine Mile Road" to reflect his mood. The British trip-hop band Morcheeba (Paul and Ross Godfrey and Pete Norris) heard a demonstration tape of the song, and offered to produce it and several other tracks for White's second album, No Such Place. Sade and Sweetback producer Andrew Hale also offered his production services and the use of his studio. In addition, Yellow Magic Orchestra and World Standard producer Sohichiro Suzuki contributed production services, which White described on the Luaka Bop website as "a crackpot love letter to all those lost souls out there like me who won't settle for wrong, but have no clue how to get it right." While recording the album, Jeremy Lascelles, publishing head of Chrysalis, offered White a publishing deal that included a generous advance that allowed White to settle all his debts. "There's a lot of good people out there who've helped me get my ducks in a row," he continued, "and, thanks to their kindnesses, for the time being anyway, me and my little family have given the slip to them spooks that've dogged me all my life."