Jim Howard Thome biography

Date of birth : 1970-08-27

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Peoria, Illinois

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-11-12

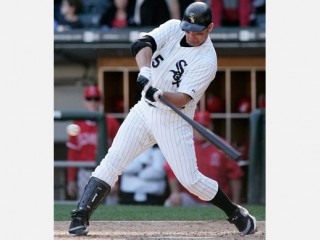

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, first baseman with the Philadelphia Phillies,

0 votes so far

During the 1930s, Jim’s grandfather thought of pursuing a career in the big leagues, but couldn’t turn down steady work at the Hiram Walker Distillery when it opened up. Carolyn was such a talented softball player that Caterpillar Tractor gave her a job in the mail room when she was 15. The company was desperate for her to suit up for its women's team, the Dieselettes.

Jim's father was also a legend on the local softball diamonds, playing in a circuit known ominously as the Outlaw League. More than once he faced fireballing Eddie “The King” Feigner and his Court. Though Chuck didn’t run or field particularly well, he was such a menacing hitter that teams often paid him to swing the bat for them.

Jim’s two oldest brothers, Chuck III (whose nickname is Caveman) and Randy, were also talented athletes. Both starred at Limestone Community High School, then played competitive fast-pitch softball after they graduated. The games were do-or-die contests that brought out the worst in everyone on the field. It wasn't uncommon for a brawl to break out at a bar somewhere afterwards. Jim idolized his brothers, and though he was more than 10 years younger than each, he tagged along whenever they let him. From Chuck and Randy he learned the value of intensity and focus.

The Thome boys also passed down their years of hitting knowledge to Jim. When Randy saw his kid brother take his first cuts right-handed, he coerced Jim into moving to the other side of the plate. Left-handers, he explained, were better hitters. And that was that.

Jim loved to swing the bat. He awoke many mornings at six sharp for “batting practice” in the Thome’s white-rock driveway . Armed with an old aluminum bat, Jim pelted one stone after another across the street and down the block. The ritual drove the neighbors crazy. Once Jim smashed a window on a nearby house. Petrified, he sprinted into his room and hid under his bed. Jim’s dad paid for the window—and contributed to his budding baseball career in other ways. Though he worked long days building bulldozers for Caterpillar (he retired in 1993 after 40 years with the company), Chuck always found time to throw BP or hit grounders to his youngest son.

Jim’s dad also accompanied him to his first Cubs game. This memorable event, now a part of Wrigley Field lore, took place during Jim’s eighth summer. His favorite player was Dave Kingman, a disagreeable man even on his best days. After “Kong” rebuffed the youngster’s autograph request and disappeared into the locker room, Jim waited for his chance and hopped the wall. He got all the way into the dugout and was making his way toward the clubhouse when Barry Foote nabbed him. The Chicago catcher explained Kingman's personality quirks, then got Jim a ball signed by several teammates.

Those precious seconds he spent in a major league dugout convinced Jim that he wanted to be a major leaguer when he grew up. He watched Cubs games on WGN, and spent endless hours practicing on his own and playing pick-up games with friends. Jim wasn't particularly big for his age, but he had his family’s baseball genes. He was also a hard-nosed competitor always looking for ways to improve and win. In a blue-collar town like Peoria, that quality was as important as any.

Jim’s work ethic and natural ability served him well on the basketball court, too. He entered Limestone High as a freshman in the fall of 1984, and developed into an All-State performer at guard. During one season, Jim led the Rockets to the conference title, scoring 36 points in a triple-overtime victory in the championship game.

Jim also made headlines on the baseball field. As a junior, he played shortstop and slammed 12 home runs, which led all high-schoolers in 1987. Jim hoped to get noticed by pro scouts, but at 6-2 and 175 pounds he was considered a bit too gangly and attracted only passing interest. The Cincinnati Reds considered taking him in 1988, then ignored him on draft day.

Three months later Jim enrolled at Illinois Central College, where he continued his basketball and baseball careers. He had a strong campaign for the Cougars in the spring of 1989, earning recognition as a Junior College All-American honorable mention.

The Cleveland Indians were impressed enough to select Jim in the 13th round. It was quite a draft for a club that was sucking wind at the major-league level. Also taken by the Tribe in ’89 were future big leaguers Jerry DiPoto, Curt Leskanic, Alan Embree, Kelly Stinnett and Brian Giles. Thrilled to be drafted by a Midwest team, Jim joined the franchise's affiliate in the Gulf Coast League. There the skinny 18-year-old batted just .237 in 186 at-bats, and failed to hit a single home run.

During the off-season, Jim remained in the Sunshine State to play in the Florida Instructional League. Over the summer he had developed a bond with Charlie Manuel, a coach in the Cleveland organization, and the two continued to hone Jim's game that winter. In the years that followed he often sought Manuel's advice when he fell into a slump or needed to get his head on straight.

ON THE RISE

Jim started the 1990 campaign with Class-A Burlington in the Appalachian League, where he showed potential as a power hitter. In 34 games, he batted .373 with 12 homers and 34 RBIs, earned an All-Star nod and was chosen for Baseball America’s All-Short Season team. The Tribe promoted Jim to its more advanced Class-A affiliate in Kinston, where he maintained a .300 average. At season’s end the organization presented Jim with the Lou Boudreau Award—given annually to Cleveland’s best minor leaguer.

Thome kept climbing through the ranks in 1991. Now an everyday third baseman, he began the season with Class-AA Canton-Akron, where he terrorized opposing hurlers. By mid-summer he was batting .337—best in the Eastern League—and though his home run total was down, the Indians rewarded him with a promotion to Class-AAA Colorado Springs. When Jim demonstrated he could handle the pitching in the Pacific Coast League, Cleveland called him up to the big club.

Jim made his major league debut on September 4 against the Minnesota Twins in the Metrodome. Starting at the hot corner, he collected two hits with an RBI and scored a run. A month later he clubbed the first home run of his major-league career, an upper deck shot off Steve Farr at Yankee Stadium. Jim finished the campaign with at least one hit in six of his last seven games. Upper Deck and Baseball America named him the American League's Best Hitting Prospect.

Jim went into the winter focused on sticking with the Indians the following spring. With GM John Hart pulling the strings, Cleveland was in the midst of an aggressive rebuilding program. To be a part of the mix, Jim knew he had to develop more patience at the plate. A pure fastball hitter, he had a tendency to wave at curveballs and splitters in the dirt, and big-league left-handers gave him a lot of trouble. Jim also worked hard on his defense at third, where his range was limited.

A strained right wrist derailed Jim in spring training, and the Indians assigned him to Canton-Akron for a rehabilitation stint—during which he hurt his right shoulder. Jim returned to full health in June, and Cleveland wasted no time calling him back to the majors. But the 21-year-old struggled, and soon found himself back in the bushes, this time at Class-AAA Colorado Springs. Ever the organization man, Jim sucked it up and went on a tear, with14 RBIs in 12 games as the Sky Sox won the PCL championship.

Feeling they might have been rushing him, the Indians asked Jim to start the 1993 campaign with Charlotte of the International League. Jim scorched the ball all year. Honored as the Topps IL Player of the Month in June, July and August, he was the circuit's leading hitter and run producer. The most encouraging aspect of Jim’s 1993 campaign was the way he honed his power stroke. He belted 25 home runs, doing so with a Hollywood flourish. He and Charlie Manuel borrowed a device from “The Natural” to trigger his swing, with Jim pointing his bat at the pitcher (a la Roy Hobbs) as he dug into the batter’s box. It is still a part of Jim’s pre-pitch routine.

The Tribe recalled Jim on August 13, and he homered in his first game, off southpaw Craig Lefferts of the Texas Rangers. Two weeks later he celebrated his 23rd birthday with a pair of doubles and a round-tripper in a 9-2 victory over the New York Yankees. When the campaign ended, the awards flooded in, including the International League Player of the Year, Baseball America AAA Player of the Year and Topps International Player of the Year.

Jim was installed as the Indians' starting third baseman to open the 1994 campaign. Excitement in Cleveland was running as high as ever. The club christened its new state-of-the art stadium, Jacobs Field, and the Tribe boasted its best lineup in years. Kenny Lofton, Carlos Baerga, Albert Belle and Sandy Alomar Jr. were all coming into their own, and Eddie Murray offered a booming veteran bat in the middle of the order. With Jim and fellow slugger Manny Ramirez poised to take on bigger roles, the Indians had all the offense they needed to conquer the curse of Rocky Colavito. Since trading the handsome young slugger after the 1959 season, the club had been in a 35-year tailspin during which it did not challenge for the pennant even once.

If the curse were to continue, manager Mike Hargrove knew that it would most likely strike his pitching staff. Dennis Martinez was signed to anchor the mound corps, but Charles Nagy, Jose Mesa, Albie Lopez and Mark Clark were anything but sure bets.

As it turned out, the pitching performed extremely well in ’94. Martinez, Nagy and Clark had all reached double digits by August 11, when a labor dispute ended the season prematurely. The Indians had been in the hunt all summer, spending significant time atop the Central Division. The offense was dominant, particularly Belle, who batted .357 with 36 homers in 106 games. Jim also emerged as a threat at the plate, especially at Jacobs Field. Early in the season he befriended Murray, who over time taught him the ins and outs of being a professional hitter. Jim was in the comfort zone when the season ended, finishing tops among AL third basemen with 20 homers. His average was .266 but on the rise, and nearly half of his 86 hits went for extra bases. His biggest day was a three-homer outburst against the White Sox on July 22.

Jim came into spring training of 1995 ready to work on his two glaring flaws. He vowed to improve on his .167 average against southpaws as well as his 15-error performance at third. Gloveman David Bell was in camp, and rumor had it that Jim was ticketed for first base. He worked tirelessly with former third sacker Buddy Bell (ironically, David’s dad) and eventually convinced the brass that he could handle the job. This development would prove vital to the team’s success in ’95. It enabled Cleveland to trade Bell to the Cardinals for starting pitcher Ken Hill, which in turn allowed Mesa to move to the bullpen and become the closer.

Two more veterans—Orel Hershiser and Dave Winfield—joined the club, giving the Indians a nice mix of youth and experience. They stormed to a 100-44 record, the best in all of baseball. Hershiser and Martinez were brilliant, while Mesa saved a league-high 46 games. Lofton did a nice job setting the table for Ramirez and Belle, who produced more than 100 extra-base hits. As for Jim, he set personal highs in almost every offensive category, including homers (25), RBIs (73), runs scored (92), hits (142), and batting average (.314). He drew 97 walks, which helped produce the league's third-best on-base percentage, and he raised his average versus left-handed pitching to .275. He was also named to The Sporting News All-Star team.

The Tribe entered the playoffs as the AL favorite to go to the World Series. They didn’t disappoint, handling the Boston Red Sox in the first round, then defeating the Seattle Mariners in the ALCS. Jim had trouble getting on track in the post-season, collecting just two hits in three games against the Bosox. But he began to swing a hotter bat against the Mariners. His clutch 440-foot homer in the sixth inning of Game Five helped send Cleveland to the World Series for the first time since 1954.

The Indians and Atlanta Braves tangled in six tense games, all but one of which were decided by a single run. Cleveland dropped the first two contests in Atlanta, won Game Three in extra innings at Jacobs Field, but dropped the next game to go down 3 games to 1. Jim saved the day in Game Five. He broke a 2-2 tie with a run-scoring hit in the sixth inning, then later smashed a long solo home run which proved to be the difference in a 5-4 win for the Indians. Game Six was a classic, with the Braves scoring the game’s only run on a homer by Dave Justice to win it all. Jim finished the post-season with four home runs and a team-high 10 RBIs—and an unquenchable thirst for a championship.

MAKING HIS MARK

Jim’s first exposure to a national baseball audience earned him a great deal of recognition. With his chin out and his socks up high, he was lauded as a throwback by writers and broadcasters. Jim’s honest, nose-to-the-grindstone approach was enormously appealing to fans, particularly in the Midwest, and for the rest of the decade he would come to symbolize everything that was good about baseball in Cleveland.

In 1996, Jim exploded for 38 home runs and 116 RBIs, to go along with a .311 batting average. He also became only the second Indian, along with Al Rosen, to score more than 100 runs, hit more than 30 dingers, draw more than 100 walks, and drive in more than 100 runs.

Cleveland won its division again, with solid pitching and good years from the team’s other offensive stars, but faltered in the playoffs. The bullpen failed, coughing up two late leads and letting a third game get out of hand against the Baltimore Orioles in the Division Series. Jim cracked his hamate bone on an awkward swing in Game One, but played the rest of the way anyhow. The pain kept him from driving the ball, but he adjusted and still hit .300. A month later he had surgery.

Despite a disappointing conclusion to 1996, the Tribe expected a big year in 1997. Over the winter, the team picked up Gold Glover Matt Williams. Julio Franco had played first base during the previous campaign, but Cleveland needed a slugger at that position, especially with the free-agency departure of Belle to the division-rival White Sox. The power shortage was addressed in part with a deal that sent Lofton to the Braves for Marquis Grissom and Dave Justice, and the promotion of young Brian Giles to the starting lineup. With the slick-fielding, power-hitting Williams at third, Jim moved across the diamond and the lineup seemed set.

Manager Mike Hargrove, a former first baseman, counseled Jim on his footwork and defensive responsibilities, and he quickly became comfortable at his new position. That translated to a good start at the plate, which helped convince the club to sign him to a contract extension worth $24.5 million. In July, Jim was named to the All-Star team for the first time in his career.

As expected, the White Sox challenged all year for the Central Division lead. Jim carried the load down the stretch, finishing with 40 homers, 102 RBIs, 104 runs, and 120 walks. He was the first AL lefty to put up such numbers since Carl Yastrzemski in 1970.

The Indians opened the playoffs against the Yankees, who had beaten the Orioles in the ALCS in 1996 and then scored a great World Series comeback against the Braves. The defending champs took it to the Tribe in the early going, but a dramatic homer by catcher Sandy Alomar against Mariano Rivera turned the series around and the Indians advanced. In a return match with Baltimore, the Cleveland bullpen proved the difference during a taut six-game series. The Indians reached their second World Series in three seasons—this time against the Florida Marlins, a team pieced together for a one-year run by multimillionaire Wayne Huizenga.

Jim, whose bat had been silent during the playoffs, came to life against the Marlins’ formidable pitching staff. He homered in two of the first three games, adding to the drama of a series that see-sawed back and forth. In Game Seven, the Tribe appeared to be in command, but the Marlins scratched out a run in the bottom of the ninth to send the contest to extra innings tied at 2-2. Two innings later, Edgar Renteria won it for Florida with a soft single up the middle.

Jim spent all winter in Peoria ruminating over the scratch hit that had cost him a championship ring., growing more determined than ever to return to the post-season. Hart felt the Indians required only finetuning to accomplish this task. He traded Matt Williams to the Arizona Diamondbacks for Travis Fryman and cash, which he used to re-sign Kenny Lofton. Other than these moves, the roster remained largely unchanged, and as expected Cleveland outdistanced Chicago by nine games to take the Central crown for the fourth year in a row.

Jim was in the midst of a torrid summer when he was plunked by Wilson Alvarez in a game against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. X-rays revealed a break in the 5th metacarpal bone of his right hand, which sidelined him for six weeks. At the time, Jim was hitting .303 with 33 doubles, 29 home runs and 83 RBIs. Fans in Cleveland worried about his availability for the playoffs. But Jim eased their concerns when he returned September 16 and went deep in his first at-bat.

The Indians disposed of the Red Sox in the Division Series, then met the Yankees to the decide the pennant. Jim torched New York pitching, with four homers (including a grand slam off David Cone) and eight RBIs, and the Indians seemed in control after winning two of the first three games. But the Yanks came back to take the next three on the lights-out pitching of Orlando Hernandez, Ramiro Mendoza and Mariano Rivera. Jim’s six post-season homers tied a mark shared by Bob Robertson, Lenny Dykstra, Bernie Williams and Griffey Jr., but did nothing to ease the sting of another frustrating series loss.

The 1999 season saw Jim take an important step in his baseball career. Instead of waiting for a good pitch and putting the ball into play, he began concentrating on pure power hitting. This meant letting decent pitches go for strikes in the hope of getting something he could belt out of the park. In a July game against the Royals, Jim caught one just right and sent it screaming into the seats, 511 feet away.

This new approach brought Jim’s average down a bit, but also resulted in a league-high 127 walks. Working deeper into the count did have its downside, however, as he also led the AL with 171 strikeouts. The last guy to lead the league in walks and whiffs was Mickey Mantle, in 1958. Jim’s power numbers were a Mantle-like 33 homers and 108 RBIs.

For the fifth consecutive year, the Indians qualified for the post-season, and again they squared off against the Red Sox. This time, Boston got the best of them in five games. Jim did everything he could to prevent the outcome, pounding Bosox pitching with a .353 average, four home runs and 10 RBIs. In Game Two he connected for a grand slam to become the first player in big-league history to hit two playoff homers with the sacks filled.

During the off-season, Jim reassessed his career. He was now carrying 245 pounds on his 6-4 frame, but the extra weight was starting to take a toll on his back. He went on a fitness program, slimmed down and improved his agility. Entering the 2000 campaign feeling better than he had in years, he was excited for another run at a title. The Indians were also gearing up for a successful run, with the same kind of balance as in their World Series seasons.

For some reason, the team never quite clicked. Although everyone’s stats where they should have been after 162 games, injuries and inconsistency kept the club from fulfilling its potential. Hart attempted to remedy the situation with several trades, but the Indians could not fend off the White Sox, who edged them for the division title. Little of the blame could be laid at Jim’s door. He hit 37 homers with 100-plus runs, RBIs and walks. He also notched his 200th homer and 1,000th hit.

An important part of Cleveland’s pennant hopes departed after the 2000 season, as Manny Ramirez signed with the Red Sox. The club moved quickly to replace this right-handed power, signing Juan Gonzalez and Ellis Burks.

The loss of Ramirez put more pressure on Jim to produce. After a miserable April, he began to heat up and stayed hot all summer. He homered in five straight games during one stretch, and had a July that would represent a good season for many players. He hit .381 for the month, with 12 homers and 39 RBIs, the most by a big leaguer in July since Cecil Cooper drove in the same number in 1983. For the first time in his career, Jim was among the front-runners for the MVP award.

In the midst of his big season, Jim learned that his 15-year-old nephew, Brandon, fractured a vertebrae in his neck in a swimming pool accident and was paralyzed. He used the sobering news to motivate him the rest of the way, as the Indians held off the fast-improving Twins to reclaim the Central Division title. In the first round of the playoffs, however, Cleveland was beaten by the Mariners, who had won 116 games. Jim’s bat was silenced by the Seattle mound corps, who were mindful of the fact that he had just produced career highs in home runs (49) and RBIs (124).

The off-season was not a good one for Jim. He worried about his nephew and replayed the loss to Seattle— keyed by soft-tossing Jamie Moyer—again and again in his mind. He also watched with some dismay as the Tribe retooled and rebuilt. With the White Sox and Twins gaining ground, the club decided to jettison some of its older, more expensive talent and work some young guys into the lineup. This put Jim, who was entering the final year of his contract, in a tricky position. He loved Cleveland and hoped to finish his career there. The fans felt the same way. But he knew the team would not be competitive in the bidding war that was sure to come. Jim didn’t mind taking less money to stay in an Indians uniform, but he looked at the personnel that would be surrounding him and doubted whether he would still be in his prime when they were ready to challenge for another pennant.

Jim’s suspicions proved correct as the 2002 season played out. The Indians finished 14 games under .500.

Nonetheless, Jim thrived under the weight of his uncertain future. He batted .304, drove in 118 runs and clouted a franchise-record 52 homers—second most in the majors behind Alex Rodriguez. He set another club mark with home runs in seven consecutive games during a hot streak from late June to early July. Over the second half of the season, he hit .338, the fifth-best average in the AL. To his credit, Jim gave Cleveland every chance to re-sign him. The club offered $60 million over five years—a figure far below his market value—but when Jim asked for a sixth season, the Tribe balked.

The Phillies, in the market for a big-time first sacker to help christen their new stadium in 2004, pursued Jim hard. Playing in a weak division with a solid everyday lineup and exciting pitching staff, Philly seemed like the perfect place to go. In December, Jim agreed to a six-year, $85 million deal, with a $12 million option for a seventh year.

As he suspected, leaving Cleveland proved a gut-wrenching experience for Jim. He talked with Pete Rose, who had gone through a similar situation when he left Cincinnati for Philly in 1979. Rose told him that Phillie fans—notorious for turning on their own superstars—would support any player who was passionate and played hard day in and day out. Rose’s observation made Jim's scenery change a bit easier.

The transition to Philadelphia was smooth. Off the field, Jim was welcomed with open arms, everyone understanding that he had the game and experience to deliver a championship to the City of Brotherly Love. Surrounded in the lineup by Bob Abreu, Pat Burrell, Mike Lieberthal, David Bell and Jimmy Rollins, Jim was being counted on to provide power and clutch hitting. The Phillies—who believed Randy Wolf, Vicente Padilla, Brett Myers and Brandon Duckworth would continue their development into top-flight starters—also upgraded their pitching, bringing in Kevin Millwood to headline the rotation. And heading up a deep bullpen was former Tribe teammate Jose Mesa, still going strong five years and 25 pounds later at the age of 37.

Jim was obviously key to Philadelphia's fortunes. Adjusting to new pitching patterns was going to take some time, and he no longer benefitted from the friendly confides of Jacobs Field, where he was a particularly effective hitter. But Jim had always been a gamer. He was quickly embraced by the Philly fans, and NL pitchers realized that they had just as much to learn about him as he did about them.

That was readily apparent down the stretch as Jim carried the Phils in their drive for the Wild Card. Like the rest of the NL East, the club was buried early in the year by the Braves, meaning a division title would not be the ticket to the playoffs. Still, Philadelphia stayed in solid position for a postseason berth. Millwood took to his role as the staff ace, the lineup provided timely hitting, and Mesa seemed to have his same old stuff.

But heading into August, the season began to unravel. Bell was lost to an injury, Burrell couldn’t snap out of a dreadful slump, and the bullpen coughed up one lead after another. The only thing keeping Philly in contention was Jim’s bat. Time and again, he came up in big spots, and produced clutch hits. In fact, over the campaign’s final two months, Jim slammed 20 homers and drove in 51 runs—despite being pitched around.

The rest of the Phillies didn’t match their leader’s effort. In the last week of the year, with a shot at the Wild Card, the team went to Florida for a crucial three-game series, and got swept by the Marlins. For all intents and purposes, the season was over for Philadelphia.

From a personal standpoint, Jim has to consider his first year in Philly a success. At .266 with 47 home runs and 131 RBIs, he put up the kind of numbers that fans and the media expected of him. Jim also established himself as the heart and soul of the Philadelphia clubhouse.

As the 2004 season began, the Phillies were picked by many baseball experts to win the NL East. While division rivals Atlanta and Florida had to cope with major losses, Philadelphia added lefty starter Eric Milton, plus proven closers Billy Wagner and Tim Worrell to strengthen the bullpen.

Jim batted in the middle of a formidable lineup that didn't change much from '03. Despite a thumb injury, he got off to a great start, hitting .289 with 28 homers and 61 RBIs as the Phillies reached the All-Star break in first place. But with Atlanta, Florida, and New York all on their heels, they were far from shoe-ins to reach the playoffs from the first time since 1993.

Unfortunately for the Phils and their fans, the campaign disintegrated in the second half. The club suffered a pair of painful defeats at home to the Mets in July, and things only got worse from there. Philly was crippled by a seven-game losing streak in August, which helped the Braves build a safe lead in the NL East. Jim was still putting up big numbers, but he wasn't hitting consistently in the clutch. When Philly's starting pitching crumbled, the team was sunk.

Despite a late surge to finish at 86-76, the Phillies wound up watching the playoffs from home. Bowa got the axe, a move that was good news to some in the clubhouse. Jim, never one to blame his manager, shouldered some of the responsibility for his team's woes. Granted, the 34-year-old slugger had a good season on paper. Jim hit .274 with 42 homers and 105 RBIs, and was named to his first NL All-Star team. But when Philly needed an extra jolt of energy from him, he wasn't able to produce.

The 2005 was even more frustrating for Jim. The Phillies and Marlins were picked as the favorites to win a highly competitive NL East, but once again the Braves made their way to the head of the pack. Philly wound up finishing two games behind, with 88 wins to Atlanta’s 90. The Astros, who would go on to capture the pennant, edged the Phils for the Wild Card with 89 victories.

Jim never really got untracked, beginning the year with a bad back and developing a sore elbow in June. He was a non-contributor the rest of the way—batting .207 with seven homers in 59 games—eventually going under the knife. His replacement, Ryan Howard, had a Thome-like second half, making the big guy instantly expendable.

In November, the Phillies traded Jim to the world champion White Sox, who had just parted ways with Frank Thomas. Philadelphia got Aaron Rowand in return, but had to fork over half of the $46 million remaining on Jim’s contract. With Paul Konerko ensconced at first base, Jim is slated for full-time duty as Chicago’s DH.

His elbow on the mend and the burden of full-time fieldwork removed, Jim is a good bet to rediscover his stroke in the Windy City. Thrilled to be playing in his home state, he should be a positive influence in the clubhouse. With any luck, White Sox fans could be seeing a lot of left-handed team records fall over the next few seasons. The new Comiskey is a band box and, when healthy, Jim is a true instrument of destruction.

JIM THE PLAYER

Jim has made himself into a classic slugger. He is extremely patient at the plate, with power to all fields. He swings through some pitches, but in general he forces enemy hurlers to put the ball over the plate if they want to get him out. That explains how he can maintain a .300 average and still whiff 150 times a year. Even when he's slumping at the plate, he is dangerous because one swing of his bat can turn the tide of any game.

At 6-4 and 220 pounds, Jim isn't particularly nimble at first. His range is average, and his footwork is sometimes clumsy. But thanks to his old third baseman’s hands, Jim can snag just about anything hit his way. He also keeps his head in the game like he’s still at the hot corner, and thus is always positioned correctly.

Jim is a leader who inspires his teammates as much through deeds as words, and by all accounts is one of the most likeable people in baseball. His love of the game is both genuine and contagious—something that can only help the Philadelphia clubhouse.