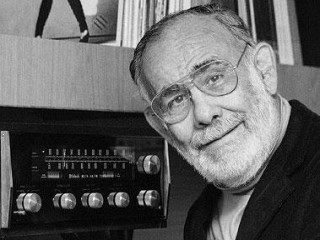

Jerry Wexler biography

Date of birth : 1917-01-10

Date of death : 2008-08-15

Birthplace : Bronx, New York City,U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2012-03-13

Credited as : music journalist, Music producer, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

1 votes so far

At the age of 12, Jerry Wexler was a New York City brat, hanging out at Artie's poolroom on 181st Street in Washington Heights and learning to talk fast and act tough. These traits would serve him well in the recording industry. In 1952 Wexler became a producer at fledgling Atlantic Records, an independent label dedicated to the genre that Wexler himself rechristened "rhythm and blues" in a 1941 Billboard article.

With an intense passion for jazz and soul, Wexler became an expert at distinguishing talent, and during his years at Atlantic, he launched many artists who became world- famous: Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, the Clovers, and the Drifters. He also discovered country legend Willie Nelson before the singer moved to CBS Records and stardom. Wexler's enthusiasm and intellectual edge, in fact, provided the support necessary for many artists' best work. Among the plethora of musicians he has promoted are Joe Turner, Wilson Pickett, Patti LaBelle, Cher, Sam and Dave, Dr. John, Doug Sahm, and Etta James.

The Washington Heights area where Jerry Wexler grew up was a hodgepodge of poor immigrants--many of whom had just arrived in the United States. Wexler's mother, Elsa, who married Wexler's Polish immigrant father, Harry, in 1916, had aspirations about a literary life for her unmotivated son. Elsa scrimped and saved tuition for preparatory schools, and Jerry promptly flunked out of all of them. Ultimately, he took a job with his father, washing windows. Throughout his youth, however, Wexler managed to make frequent visits to Manhattan nightclubs, featuring swing and the big bands-- Fletcher Henderson at the Savoy, Jimmy Lunceford, Count Basie, and Benny Goodman. Wexler read books about jazz and blues, and collected the latest 78 rpm records.

After a stint in 1936 at Kansas State College, where he studied journalism--and haunted the wild Kansas City clubs--Wexler returned to New York. He fell in love with a teenager named Shirley Kampf, and as a sign of his adoration, he took her to see Ella Fitzgerald and Chick Webb at the Apollo Theater. Shirley became his confidant and co-worker for the next two decades. After marrying in 1941, the couple moved in with Wexler's father, who was temporarily estranged from Elsa. Wexler finally landed a job, as a customs officer, but was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1942.

As noted in his 1993 autobiography, Rhythm and the Blues: A Life in American Music, Wexler credits the army for instilling discipline into his character. He received a stateside assignment as a military police officer, presumably because of his customs experience. In Miami Beach, Florida, then in Wichita Falls, Texas, he was responsible for administering behavioral tests. After his discharge, he went back to Kansas State to finish his degree, began to write, and had a few articles published. He then headed to New York City to look for a newspaper job. Unsuccessful in his search, he found work at the newly formed Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI), a radio group challenging the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers' (ASCAP) domination of the music publishing industry. A bout with pneumonia forced Wexler to give up that position, but Billboard magazine soon hired him. Now 30, he was able to move with his wife into his first apartment.

Two lifelong preoccupations surfaced in Wexler at this time: bebop--the music of Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie--and the food of the great Broadway delis like Lindy's on 51st Street. The song peddlers who frequented the restaurants, especially a man named Juggy Gayles, introduced Wexler to the world of record production. In his position of reporter for Billboard, Wexler chose from the thousand of demos that crossed his desk, the "Tennessee Waltz," and gave it to singer Patti Page's agent, Jack Ruel. She recorded it as the B-side of "Boogie Woogie Santa Claus," and it became her signature song. Wexler can also take credit for alerting Mitch Miller of Columbia Records to two songs that became Number One hits: "Cry" performed by Johnny Ray, and a Hank Williams tune, "Cold, Cold Heart," sung by Tony Bennett.

Eventually, a rift developed between Wexler and Billboard's editors. According to Wexler, during the McCarthy era--when many Americans entertainers were being blacklisted for their alleged communist leanings--he had refused to work up a blacklist dossier on the folk group the Weavers. He left the magazine in 1951 to become promotions director for MGM Studios' music publishing division, the Big Three. His reputation earned him a job offer from Atlantic Records, but he turned it down; he had insisted upon being made a partner. A year later, the owner of Atlantic, Ahmet Ertegun, acquiesced to Wexler's demand when Ertegun's partner, Herb Abrahamson, left to join the army. Wexler raised $2,063.25 to claim a 13 percent share of the company. Ertegun in turn used the money to buy Wexler a green Cadillac with fins.

Ertegun and Wexler were well matched: Ertegun was cool while Wexler was frenetic. Both men had an extensive knowledge of literature and art, as well as of rhythm and blues. Their office over Patsy's Restaurant at 234 West 57th Street became a beehive of sessions that put Atlantic Records on the map.

The Atlantic Records business was run like a mom-and-pop grocery. Wexler worked intimately with the performers, helping Clyde McPhatter of the Drifters, for example, write "Honey Love" and playing tambourine for Ray Charles. Atlantic succeeded in changing the negligent attitude that record labels traditionally had taken toward black music. Wexler treated the performers with respect, rehearsing and developing clear, precise harmonies. He produced recordings for LaVern Baker, then Joe Turner, and, most notably, Ray Charles. Wexler claimed that he merely stood back and let the great pianist invent, but Charles' work at Atlantic--combining bebop, gospel, and blues--proved to be his finest.

By 1956 Wexler was producing a dozen recording acts. He bid $30,000--an amount he did not have--for Elvis Presley, but lost out to RCA's $40,000 offer. He soon hooked up with Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller, a songwriting team that created a steady output of pop music masterpieces, including "Stand By Me," "Charlie Brown," "Poison Ivy," and "There Goes My Baby." Wexler's hustle kept the then- independent Atlantic Records label competitive with the deep-pocket major studios. In the 1960s Atlantic brought guitarist Jimmy Page to the United States from England, and Page's band, Led Zeppelin, became Atlantic's biggest seller.

Ertegun and Wexler became estranged during the 1970s, as Ertegun's taste switched to the more lucrative pop acts, and Wexler became notorious for backing purist failures in the R&B realm. As Ahmet gravitated toward Los Angeles and London, Jerry headed south to Tennessee, Alabama, and Florida. He was a pioneer in the southern renaissance that merged R&B and country sounds. One of Wexler's best-known projects was Aretha Franklin, a gospel singer who blossomed under the producer's auspices. She reworked blues performer Otis Redding's "Respect" on her first album, and the song became a feminist anthem.

Wexler's personal life, however, suffered from his workaholic nature. His wife, Shirley divorced him in 1973 when she discovered that he was seeing another woman, Renee Pappas, whom Wexler promptly married. He would later cope with the death of his daughter Anita of AIDS in 1989. A professional association ended as well when he sold his share in Atlantic to smooth over friction with Ertegun.

In 1985 Wexler moved to Sarasota, Florida, and married playwright and novelist Jean Arnold. He continued to pursue independent projects, working on film director Francis Ford Coppola's The Cotton Club and Jelly's Last Jam on Broadway. He joined forces with folk troubadour Bob Dylan for the singer's Christian albums Slow Train Coming and Saved. In the 1990s, having reached his seventies, he was still producing, making an album called The Right Time with his old friend Etta James.

Jerry Wexler died at his home in Sarasota, Florida, on August 15, 2008, from congestive heart failure. Asked by a documentary filmmaker several years before his death what he wanted on his tombstone, Wexler replied "Two words: 'More bass.’”