Jeff Kent biography

Date of birth : 1968-03-07

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Bellflower, California

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-11-04

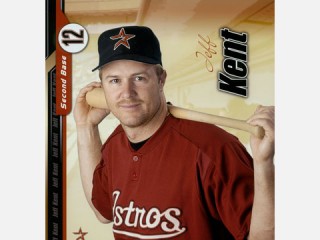

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, second base with the Houston Astros,

0 votes so far

Jeff was not what you would call laid-back. From earliest childhood he was an intriguing combination of both parents. Sherry Kent, a loving mother and homemaker, passed along her nurturing instincts, teaching him to always care about the welfare of others. An independent thinker, she also instructed her son to have opinions of his own and be confident in his convictions.

Alan Kent was another proposition entirely. A motorcycle cop who rose through the ranks to lieutenant, he was a demanding parent not given to idle chitchat. Alan hated to lose and was somewhat of a thrill-seeker. While studying to become a police officer, he broke a shoulder in a motorcyle accident. He sucked it up, continued training and graduated on time.

From the moment he entered the world, Jeff had a special bond with his dad. Among his fondest memories is wiping down Alan's motorcycle with a ratty, old t-shirt. The youngster took everything his dad said to heart. Alan told his son that no job was worth doing unless it was done right, and made sure that he never settled for anything less than his best.

Those lessons translated directly to Jeff's athletic career. All three Kent boys shared their father's love of excitement and adventure. They raced dirt bikes and surfed. Jeff's first sports heros were Marty Motes, Jeff Ward and Bob Hannah, all Moto Cross competitors. Jeff also acquired an affinity for the life of a cowboy. John Wayne was one of his childhood idols, and he still smiles about the day he got the Duke's autograph.

Baseball was of interest to Jeff, though it would be a stretch to say he loved the game. He didn't follow any one team or player closely, despite the fact the Dodgers were winning pennants in nearby Chavez Ravine. Still, Alan pushed his son to cultivate his natural talent in the sport. Though of average size for his age, Jeff was a powerful hitter and dominant pitcher. When Alan played catch with his son, he hammered home the need for perfect execution. If one of Jeff's throws sailed over his dad's head, the youngster would have to fetch it. When Jeff started playing in youth leagues, he always knew when Alan was dissatisfied with his performance. A 3-for-4 day at the plate might be greeted with criticism of the out he made; a one-hitter on the mound might invite an animated exploration of “what went wrong.” Rather than burning out under this intense scrutiny, Jeff embraced his dad's ultra-intense approach to life.

Jeff took that attitude with him to Huntington's Edison High School in the fall of 1982. He went out for baseball the following spring and made the freshman team. It wasn't until his junior year, however, that he joined the varsity. His time with the Chargers was relatively short-lived. A run-in with the coaching staff Jeff's senior season got him booted off the squad.

Jeff considered his options outside of baseball after graduating from Edison. An excellent student, he had been accepted at several prestigious West Coast schools, including Stanford. The University of California, however, intrigued him the most. At the end of the summer, Jeff climbed into the Toyota 4x4 pick-up given to him by his father, and drove north to the Cal campus, just across the bay from San Francisco.

When he arrived at Berkely, he decided to give baseball another shot. Coach Bob Milano didn't know a whole lot about the freshman, but offered him a chance to make the Bears as a walk-on. Jeff caught the coach's eye with his feistiness and hard work, and surprised teammates with his live bat. By mid-season, the wiry shortstop no one in the Pac 10 had heard of a year earlier established himself as Cal's top player, and by season's end he had rapped out a school-record 25 doubles.

Though Milano didn't have an extra scholarship available, he put a few extra bucks in Jeff's pocket with a job taking care of the baseball field. The Bears posted a respectable 36-25 record in 1987, but finished 12-18 in the PAC 10, well off the pace set by eventual national champion Stanford.

Jeff had another solid season in 1988, and the Bears finished with the fourth-best record in the PAC 10. That was good enough for a berth in the College World Series. The Bears bowed out early, as Stanford, behind the pitching of Lee Plemel, repeated as national champs.

Jeff's junior year was a disaster. The Cal team took a giant step backward, winning just 10 conference games and finishing in last place. The Bears did go 25-4 outside the PAC 10, but it was small consolation for a trying season. Jeff was still on a partial scholarship, so money was tight. He often called home for cash, but his parents did not have much to spare.

Jeff's frustration affected his baseball. Although he played reasonably well, he butted heads with Milano on several occasions, and was in and out of the coach's doghouse all spring. When Jeff was selected by the Toronto Blue Jays in the 20th round of the June draft, the decision to leave school early was a no-brainer.

ON THE RISE

Jeff spent his first season as a pro playing for St. Catharines of the Class-A NY-Penn League. He was not among the organization's top prospects, but nevertheless outplayed a trio of young studs named Carlos Delgado, Ryan Thompson and Nigel Wilson. Jeff struggled at times, batting .224 in 73 games, but he also led the league with 13 home runs and was tops on the team in RBIs.

In 1990, the Jays converted Jeff to second base. He took to the position immediately, leading the Florida State League in assists and putouts while committing only 15 errors. Jeff had a superb year at the plate, too. Playing in 132 games for Dunedin, he batted .277 and amassed 50 extra-base hits, while flashing some speed with 17 stolen bases. Dunedin went 84-52 with starter David Weathers and closer Mike Timlin leading the way.

Jeff's development continued in 1991 at Class-AA Knoxville. While he was still striking out too much and his errors rose, he was turning double plays like a major leaguer and showing that he could be a good run-producer. His 34 doubles topped the Southern League, and his 61 RBIs tied him for the team lead. He also stole 25 bases.

Heading into spring training in 1992, Jeff, one of many players vying for a utility role in the infield, seemed to have little chance of sticking with the Blue Jays. A starting job was definitely out of the question—Toronto's second baseman, Roberto Alomar, was coming into his own as a great player, Kelly Gruber was solid at third, and Manny Lee and Alfredo Griffin figured to split the shortstop job.

Jeff approached spring camp as a learning experience. He confidently sidled up to veterans stars like Joe Carter, Dave Winfield and Jack Morris and picked their brains. They thought Jeff was a riot. None could remember a rookie looking so at home in a major league uniform, or acting so much like a part of a team he had yet to make! But whenever manager Cito Gaston put him in games, he got the job done.

Slowly but surely, Jeff rose above the other utility players in camp. In Toronto's second to last game of the grapefruit season, he slammed a long home run off Baltimore closer Gregg Olson, owner of a curveball known to buckle rookies' knees. The blast opened a lot of eyes in the front office, and when outfielder Derek Bell went down with an injury the brass decided to use his spot to keep Jeff, who could play all four infield positions. In his first big-league at bat, he belted a double to left-center and received a standing ovation from the crowd at SkyDome.

As the season wore on, Gaston began looking for reasons to get Jeff in the lineup. Though he had trouble keeping his average above .250, he was producing extremely well in the clutch, and half his hits were going for extra bases. An injury to Gruber created more playing time for Jeff, and by August he was starting almost every day, as the Jays battled for first place in the AL East.

Over in the National League, the New York Mets—who started the year with high hopes and an enormous payroll—were already out of the running in the East. They were looking to dump salary, and their most marketable star was righthander David Cone. Toronto, anxious to add a seasoned starter to its staff, agreed to package Jeff with Ryan Thompson to acquire Cone—who helped the franchise win its first World Series that October.

The fans in New York did not exactly roll out the red carpet for Jeff. Cone had been a very popular player, and he would be nearly impossible to replace. It did not help that Jeff batted .239 in the last five weeks of the ‘92 season; the Shea Stadium boo birds really let him have it.

Jeff was an intense young player unused to failing. His teammates, sensing that he needed to loosen up, decided to play a practical joke on him. Prior to a game in Montreal, they stole his clothes and replaced them with an eye-straining outfit from the collection of Lindsey Nelson, the club's radio and TV broadcaster. Jeff didn't get it. He reacted angrily, alienating his teammates and giving him a league-wide reputation as a crybaby and major league A-hole. For the rest of the year, no one said a word to him, which just deepened his frustration. Isolated and far from home, he was miserable.

Jeff won the second base job in spring training the following year, but manager Jeff Torborg benched him after a slow start. With the rest of the club also slumping, the bespectacled skipper lasted 38 games before being canned. His replacement, the fiery and intimidating Dallas Green, put Jeff back out in the field and told him to go kick some butt. He responded by batting .270 and establishing new team records for home runs (21) and RBIs (80) by a second baseman.

Jeff's performance was one of the few bright spots in an otherwise appalling performance by the Mets. A collection of high-priced stars built to win a division title, they proved to be baseball's most dysfunctional team and ended the year with a 59-103 record. One of the main culprits in this disastrous season was Bobby Bonilla, who had been signed as a free agent by the Mets in 1992. Ironically, the moody veteran—considered by some to be a “clubhouse cancer”—went out of his way to befriend Jeff and work with him on the weaker parts of his game.

Despite his hard-nosed play, Jeff was not a favorite of Green's. The manager chided Jeff about his propensity for striking out, and complained about his fielding, which produced a league-high 18 errors in '93. At one point, during a series against the Cubs, Green benched him for three games. Jeff was so furious that it took a visit from his wife, Dana, to calm him down. During the All-Star break the couple went house-hunting in Austin, Texas, and later purchased a home there.

Green kept the heat on Jeff in 1994. During spring training he told reporters that the second base job was open. The team had a pair of sparkplug second sackers in the minors—Fernando Vina and Quilvio Veras—and Green hinted that a move to third might be in Jeff's future.

Jeff initially responded poorly to the idea. He took potshots at Vina in the media and sulked at the prospect of switching positions. But when he rechanneled that energy into his play of the field, he began swinging a hot bat. In April, Jeff hit .375 with eight home runs and 26 RBIs. Green, in turn, had no choice but to keep him at second.

The Mets, however, were again no better than a .500 club. With youngsters like Thompson, Jeromy Burnitz, Butch Huskey, Tim Bogar, Pete Schourek and Anothony Young given a chance to prove themselves in the big leagues, New York couldn't muster any consistency. Meanwhile, the only veterans who approached expectations were Bonilla and pitcher Bret Saberhagen. The season fell apart completely when Dwight Gooden was forced to come clean about his drug addiction. The Mets were 55-58 when the season ended in August because of a labor dispute.

By then, Jeff's production had tailed off. He wound up hitting .292 with 14 homers and 68 RBI—decent numbers, but nothing close to what he showed in the first month. To his credit, he did continue to hit well with runners on base and improved his glovework at second.

In 1995, the Mets hung their hopes on the young arms of Bobby Jones, Paul Wilson, Bill Pulsipher and Jason Isringhausen. The offense featured a number of inexperienced players, which meant Jeff would have to carry the load, along with Bonilla and catcher Todd Hundley. They got help from first baseman Rico Brogna, who out-homered Jeff 22 to 20 for the team lead, but no one had anything like a breakout year. The team's four young guns combined for just 24 major league wins, and the team sunk below .500 once again.

In the spring of 1996, Green shifted Jeff to third and installed defensive whiz Edgardo Alfonzo at second. Watching Fonzie work his magic with the sensational rookie Rey Ordonez at shortstop, Jeff knew there was not much complaining he could do. Besides, his locker was situated very close to theirs and he did not want to make enemies of his infield mates. After committing four errors in his first week as a third baseman, he settled down and started to have a decent year despite another dismal campaign for the Mets. The fans kept letting Jeff have it, though, and by mid-season they were really getting on his nerves.

Thus it was with considerable relief that Jeff learned he had been included in an August trade with the Cleveland Indians, the defending American League champions. New York GM Joe McIlvaine dealt Jeff and Jose Vizcaino to the Cleveland Indians for Carlos Baerga. The trade, however, did irk Jeff on one level—he felt he had unfinished business in the National League.

The Indians acquired Jeff to help down the stretch. Used primarily as a utility infielder, he provided some punch off the bench, but not as much as Cleveland had hoped. In 102 at-bats, he hit .265 with three homers and 16 RBIs. In the Tribe's loss to the Orioles in the Divisonal Series, Jeff was barely a factor.

MAKING HIS MARK

Jeff's career was at a crossroads after the 1996 campaign. He had yet to live up to expectations, and when the Indians shipped him, Vizcaino, Joe Roa and Julian Tavarez to the Giants for Matt Williams, he joined his third team in less than a year. For San Francisco, the move was part of a major housecleaning. New GM Brian Sabean retooled the everyday lineup in search of a competent supporting cast for Barry Bonds. He acquired J.T. Snow from the Angels and Mark Lewis from the Tigers, and signed outfielder Darryl Hamilton. Jeff figured to fit in either at second or third. Regardless of which position he played, he would be filling large shoes, replacing either Williams or Robby Thompson, who had retired.

Manager Dusty Baker, hoping to ease the pressure on Jeff, made him feel like a key guy from the moment he reported to camp. Jeff responded by opening up to teammates and making several fast friends. When Snow got injured during a Cactus League game, he was the one who came forward to console the first baseman's wife, Stacie.

Baker also helped Jeff reach a new comfort level on the field by handing him the job at second base and inserting him in the lineup behind Bonds. The San Francisco manager had long been a fan of Jeff's, despite some of the horror stories he heard about his attitude. Baker believed that he was an intense competitor who hated to lose. If Jeff wasn't a clubhouse cut-up or fan favorite, so be it.

Relocating to San Francisco, near his old stomping grounds in Berkeley, Jeff felt this might be the place where he would finally settle in. With that in mind, he signed a two-year deal with the Giants, which included an option for 1999.

As the 1997 campaign opened, Jeff rewarded Baker's confidence in him, driving home 15 runs in the first two weeks of April. During that span he spearheaded a satisfying three-game sweep of the Mets at Shea, including a game in which he slugged two homers. With San Francisco's makeshift rotation of Mark Gardner, Osvaldo Fernandez, William VanLandingham, Kirk Rueter and Shawn Estes pitching surprisingly well, the Giants moved into first place in the NL West for the first time in two years.

Jeff continued his hot hitting into May, slamming his third grand slam of the year as the month drew to a close. His performance dropped off in June, after Ramon Martinez of the Dodgers plunked him on the left wrist with a fastball. Jeff, however, earned the respect of his teammates by playing through the pain. Still, with Jeff hurting, Bonds saw fewer and fewer good pitches, and the San Francisco offense sputtered. When the pitching came back down to earth, the Giants lost their hold on the division lead.

Fortunately for San Francisco, Jeff recovered by late August, and not coincidentally the team climbed back up the standings. He hit his 26th home run of the season on the second-to-last day of the month, tying him with Rogers Hornsby for the most long balls ever hit by a Giants second baseman. Down the stretch, his 11 homers and 42 RBIs keyed San Francisco's successful bid for the NL West title. The club's frenzied run ended in a first-round sweep at the hands of the Florida Marlins, who would go on to beat Jeff's former Cleveland teammates in an exciting World Series.

Overall, Jeff was pleased with his first year as a Giant. Though he batted just .250, he posted career-highs with 29 home runs and 121 RBIs. He also settled in at second, improving his range and footwork. Most noticeable was his affect on the rest of the team. Hitting behind Bonds, he made opponents pay when they pitched around the lefty slugger.

Despite Jeff's breakout campaign, few people expected him to match his numbers in 1998. Thanks to Sabean's busy off-season, however, it didn't appear that he needed to. Closer Rob Nen was brought in from the Marlins, while veterans Orel Hershiser, Stan Javier, and Charlie Hayes were also added to the roster. With the emergence of Bill Mueller at third and Rueter on the hill, the Giants went into 1998 a deeper and more balanced team.

As it turned out, San Francisco and two other teams were left to battle it out for the Wild Card when the San Diego Padres built a huge lead in the West. Sabean fine-tuned the Giants with several second-half trades, acquiring Joe Carter, Jose Mesa and Shawon Dunston among others. With two weeks remaining, however, the Giants seemed to be the odd team out. But victories in eight of their last 10 tied them with the Chicago Cubs. A one-game playoff was held at Wrigley Field, which the Giants lost, 5-3.

Despite missing the playoffs, the season was a success for Jeff. He broke from the gate quickly again, convincing the Giants that he wasn't a one-year wonder. In May the club rewarded him with a three-year, $18 million contract extension. A month later Jeff was sidelined with a sprained right knee when Alex Rodriguez rolled into him breaking up a double-play. He returned to the lineup in July, though in a bad mood because he had been left off the NL All-star team in favor of Cincinnati's Bret Boone. He took his anger out on the Reds before the month ended, with two homers and seven RBIs in a 12-2 rout.

From then on, Jeff was terrific. After being voted NL Player of the Month in August, he turned up the intensity an additional notch for the stretch run in September. In a series against the Expos, he considered charging the mound when Miguel Batista hit him. Instead Jeff let his bat do his talking, launching a long home run in his next at-bat. In the clubhouse afterwards, he spoke out against the San Francisco pitching staff, criticizing them for not retaliating on his behalf. His remarks weren't particularly well timed, but teammates gave Jeff a pass because he was so hot.

Indeed, despite missing 26 games in 1998, Jeff finished with a .297 average, 31 home runs and 128 RBIs. He also established new personal highs in hits (156), runs (94), on-base percentage (.359) and slugging (.555). Just as important, he seemed to be learning what it meant to be a leader, both on the field and in the clubhouse.

The 1999 campaign saw the Arizona Diamondbacks race past the Giants and the rest of the NL West to win the division by 14 games. The Giants never got it in gear. Nen and the starters were inconsistent, Bonds underwent elbow surgery, and despite nice years from shortstop Rich Aurilia and newcomer Ellis Burks, the team did not have the look of a contender.

Jeff nursed a sore left foot through most of the season, but continued to produce even with Bonds on the bench. On May 4, Jeff became the first Giant in eight years to hit for the cycle. In July he was named to the All-star team for the first time, San Francisco's lone representative. The Giants demonstrated their appreciation by picking up his option for 2002. Jeff ended the season at .290 with 23 homers and 101 RBIs. It marked the third straight year he topped the century mark in runs driven home—joining Bonds, Willie Mays, and Willie McCovey as the only players in San Francisco history to do so.

Despite the team's distant second-place finish in 1999, Sabean and Baker decided to stand pat with the roster they had. With the Giants ready to christen Pacific Bell Park, they believed the club had more than enough talent to contend in 2000. Livan Hernandez and Russ Ortiz showed that they could fill the rotation behind Reuter and Estes, Bonds appeared a good bet to come back at full strength, and the infield of Jeff, Snow, Aurilia and Mueller proved to be one of the most solid units in baseball.

Jeff sizzled throughout the ‘00 campaign. Playing in 159 games, he batted .334, slammed 33 homers and registered 125 RBIs. For the first time in his career, he was voted to start in the All-star Game, riding a last-hour surge in the balloting to overcome the incumbent, Craig Biggio. Jeff was also gaining more and more credibility with his teammates. On July 4, with Hernandez working on a no-hitter, he made a pair of spectacular defensive plays to keep the bid alive. Though the right-hander eventually surrendered a hit, Jeff's effort wasn't lost on anyone in his dugout.

A month later, Jeff made history by becoming the seventh Giant to record 100 RBIs in four-straight seasons. (The others are “Highpockets” Kelly, Irish Meusel, Bill Terry, Mel Ott, Mays and Bonds.) He reached the milestone with a grand slam at home off Milwaukee's Paul Rigdon. The fans at PacBell gave him a standing ovation and demanded a curtain call. Ever the sourpuss, Jeff stayed on the bench.

San Francisco took the division crown with a record of 97-65, riding on the backs of its power hitters. The Burks-Bonds-Jeff troika did most of the damage, while Aurilia, Snow and Mueller also chipped in with strong numbers. The club's starting pitching wasn't nearly as reliable, but Nen was sensational, saving 41 games with an ERA of 1.50. The Giants, however, were victimized by the Mets in the playoffs, losing in disappointing fashion to the NL Wild Card entrant. The sting of that defeat was lessened somewhat for Jeff in December when he edged Bonds for the MVP award.

After San Francisco's early exit from the playoffs, Jeff took it upon himself to be an even more commanding leader. In spring training of 2001, he requested his locker be moved to the area where most of the Giants' prospects dressed. His goal was to provide an example for players working their way through the organization—though he didn't see any need to socialize with them. While that put off some players, most understood that they could learn a lot simply by watching Jeff.

In 2001, Jeff had another good season. Though his home run total dropped to 22 and his average dipped below .300, Jeff again knocked in more than 100 runs. He also set a career high with 49 doubles.

Of course, Jeff's year paled in comparison to the one put up by Bonds, who slugged a record 73 homers. Neither player, however, was able to get the Giants back to the post-season. They battled down to the wire with Arizona, but the tandem of Randy Johnson and Curt Schilling was too much to overcome. San Francisco finished two games out of first in the West and watched the playoffs from home. Or at least most of them did. Jeff, never a “fan” of baseball, admitted that he rarely watched the playoffs and World Series after his own season was done.

This may have raised a few eyebrows, but it was nothing compared to the furor surrounding an incident that occurred in early March of 2002. Right after the team reported for spring training in Scottsdale, Jeff broke his left wrist, then was less than honest about the cause of the injury. At first he floated the story that he had hurt himself on a fall while washing his pickup truck. The media, however, soon discovered the truth: The fracture was the result of a motorcycle accident near the team's spring training complex. Jeff finally admitted that he had crashed on his bike while popping wheelies.

This news did not thrill the San Francisco front office. Though Jeff's injury was expected to heal by the beginning of the year, he had lied to the team and violated a standard clause in all major league contracts that prohibits players from engaging in dangerous activities. Ultimately, the Giants chose not to take any action against Jeff, but the episode lent more credence to his image around baseball as a selfish player.

When Jeff got off to a slow start in the regular season, he drew even more criticism. With the All-Star second baseman due to become a free agent, rumors circulated that he was on the trading block. In June, however, Jeff finally began to find his rhythm. But when he and Bonds were caught on television nearly coming to blows in the dugout, speculation that he was on his way out of town resurfaced.

By then, the Giants couldn't afford to lose Jeff. He was so hot that Baker flip-flopped his lineup, batting Jeff in front of Bonds. With the lefty providing protection in the batting order, Jeff sizzled at the plate. In his first 22 games in the three-hole, he batted .453. By mid August, he was leading the NL in hits and ranked in the Top 10 in batting, home runs, RBIs and runs.

Jeff's hot streak couldn't have come at a better time. With injuries piling up for the Giants, the team was in danger of fading from the race in the NL West. But Jeff kept the club in contention. When Sabean acquired for Kenny Lofton from the White Sox, San Francisco received a much needed spark, and by September the Giants were back in the thick of things. Ortiz, Rueter and newcomer Jason Schmidt were anchoring the rotation, while Jeff and Bonds were making life miserable for opposing pitchers. With the pair on base so often, veterans Reggie Sanders, Benito Santiago and Snow were driving in runs in bunches.

The Giants wound up winning 25 of their last 33 and captured the Wild Card. In the Divison Series they faced the Atlanta Braves, a team loaded with playoff-savvy veterans. But San Francisco was the team that played like it had been there before. Bonds made his presence felt in Game 1, and Lofton and Snow continued to swing hot bats. On the mound, Ortiz made important pitches when he had to. The Giants claimed the series in five games, taking the finale in Atlanta. Jeff was uncharacteristically quiet with only five hits and one RBI.

Jeff also struggled in the NL Championship Series, against the St. Louis Cardinals. Again, the Giants advanced without a major contribution from him. Schmidt was dominant in his start, and Tim Worrell gave the club valuable innings out of the bullpen. With Santiago, Aurilia and David Bell pacing the offense, San Francisco handled the Cardinals with surprising ease to win the pennant, four games to one.

That set up an exciting showdown between two West Coast clubs. Neither the Anaheim Angels (the AL's unexpected Wild Card pennant winner) nor the San Francisco Giants (who moved to California in 1958) had ever won a World Series. The atmosphere in the opener at Edison Field was incredible—more like a Japanese game than an American one. The Giants silenced the raucous crowd with a 4-3 victory in Game 1. The following night Anaheim pounded out an 11-10 win. Jeff got his first hit of the series in this contest, a solo home run off Kevin Appier.

That blast appeared to snap Jeff out of his slump, as he picked up two more hits in Game 3—a 10-4 loss to the Angels. The Giants took the next two games to go up 3 games to 2. Jeff knocked in a key run in the first win with a sac fly, then doubled and homered to knock in a quarter of his team's 16 runs in a Game 5 laugher.

No one on the Giants was laughing when Game 6 ended. The Giants had the game in hand when Baker yanked Ortiz, who was pitching well in the seventh inning. The Angels rallied from 5-0 to win 6-5, with Scott Speizio belting a clutch home run. In Game 7, with the wind out of their sails, the Giants fell behind early and never came back.

The heartbreaking loss turned out to be Jeff's last game in a Giants uniform. In the offseason, he made headlines when he signed a two-year, $18.2 million deal with the Houston Astros. The club cleared room for him at second when Craig Biggio, whose days in the infield were numbered anyway, agreed to move to the outfield.

The addition of Jeff to a lineup that already included Jeff Bagwell and Lance Berkman gave the Astros perhaps the best 3-4-5 punch in baseball. With the short leftfield porch in Houston and the expansive power alleys, everyone expected Jeff to continue to build on his already impressive numbers. He stared the year well, batting .300 in April with four homers and 16 RBIs. May was also a good month for Jeff, but in June an injury to his left wrist landed him on the shelf for some three weeks.

In his absence, the Astros managed to keep their heads above water, and remained in the thick of the race in the NL Central. Bagwell was enjoying a typical season, Berkman began to heat up after a sluggish beginning to the year, and Richard Hidalgo looked like a cinch to win Comeback Player of the Year.

The pitching staff, however, was dealing with injury problems. The biggest hit came when Roy Oswalt went down. Thanks to excellent work from rookie Jeriome Robertson and bullpen workhorses Brad Lidge, Octavio Dotel and Billy Wagner, Houston was able to survive without its ace.

Heading into the season’s final month, the Astros were healthy and appeared ready to take control of the division. But down the stretch the team stopped hitting in the clutch, and the starting staff wilted. The Astros watched the Chicago Cubs surge past them and win the NL Central. They also fell short of the Wild Card, as the spunky Florida Marlins clinched their first post-season appearance since 1997.

For Jeff, his first year in Houston was a disappointment. Though he posted solid numbers—a .297 batting average, with 39 doubles, 22 homers and 93 RBIs—he didn’t have the impact many predicted. To be fair, however, his production was limited somewhat by his sore left wrist.

GM Gerry Hunsicker used the off-season to focus on his rotation. First he signed free agent pitcher Andy Pettitte, and then convinced Pettitte’s former teammate and future Hall of Famer Roger Clemens to come out of retirement. With the addition of the two, Houston quickly gained an experienced postseason staff, and became a favorite to advance to the 2004 World Series.

After a rough April, Jeff came out swinging in May, hitting .346 with five homers and 28 RBIs. The hot streak came at a perfect time, as Houston was dealing with rough starts at the plate from Bagwell and Richard Hidalgo. The pitching staff was also struggling. Pettitte was on the disabled list, and Dotel was having trouble closing games.

With St. Louis running away with the division, Hunsicker sprang into action again. He traded the slumping Hidalgo to the Mets, and then pulled off a blockbuster, sending Dotel to Oakland in a three-way deal for centerfielder Carlos Beltran. Still, the Astros couldn't put it together.

At the All-Star break, Jeff joined teammates Berkman and Clemens on the NL squad to the delight on the fans at Minute Maid Park. The hometown crowd, however, didn't treat Houston manager Jimy Williams nearly as well, booing him loudly during pregame introductions for the Mid-Summer Classic. Hunsicker fired Williams days later, and tabbed Phil Garner as his replacement.

The Astros needed time to adjust to the upbeat Garner, but when they did, they took off. The offense started stinging the ball, Clemens and Oswalt carried the starting rotation, and Lidge was unhittable down the stretch. A 12-game winning streak in August and September vaulted Houston into the thick of the Wild Card race. The Astros went on to win 36 of their final 46 games, including a sweep of the Rockies on the season's final weekend to clinch a spot in the playoffs. Jeff finished the year at .289 with 27 homers and a team-leading 107 RBIs.

Houston opened the postseason on the road against the Atlanta Braves. After a 9-3 victory in Game 1, the Astros jumped out to a early lead in Game 2, but the Braves rallied and won it on an eleventh-inning home run by Rafael Furcal. In Houston for Game 3, the Astros crushed John Thomson to go up 2-1 in the series.

With Houston’s first-ever playoff series win in their sights, Clemens toed the rubber in Game 4. He pitched well, but the bullpen coughed up the lead and the Astros lost 6-5. Forced into a deciding Game 5, Houston’s offense exploded—including Jeff, who went 2-for-5 with a RBI—as the Astros cruised to a 12-3 victory.

The win advanced the Astros to the NLCS against the Cardinals. Jeff homered and drove in two runs in Game 1, but was silenced in Game 2. His performance was academic anyway, as St. Louis won both contests.

When the series shifted to Houston, the Astros came back with three victories in a row. Jeff, looking much more comfortable at the plate, hit a two-run homer in Game 3, and then played hero again two nights later. With Game 5 knotted in a scoreless tie entering the bottom of the ninth, he launched a long home run to put Houston one win away from the World Series.

But the gutty Cardinals responded on their home field. Game 6 was a nailbiter that St. Louis captured in the twelfth on a homer by Jim Edmonds. In the decider, with Clemens on the mound, Houston seized an early lead. But the Cardinals rallied in the sixth, and held on to beat the Astros 5-2.

Jeff had a decent series with three HRs and seven RBIs, but he also showed limitations defensively. In Game 7 against St. Louis, he was unable to come up with two groundballs that second basemen with better range might have fielded. Of course, that's the trade-off with a power-hitting infielder like Jeff.

Coming out of the post-season, the Astros had to decide whether to retain Jeff’s services. With Biggio and AAA phenom Chris Burke available at second and a slew of young outfielders, including Willy Taveras and Jason Lane, Jeff’s salary didn’t make any sense. They tried low-balling him in November but he declined. When Houston did not offer him arbitration, he was free to negotiate with other teams. In early December, the Dodgers signed him to a two-year deal.

The absence of Barry Bonds from the Giants’ lineup made LA the team to beat in the NL West in 2005. The Dodgers looked pretty good on paper, but the game is played on the diamond. The club hovered under .500 all year, suffering from injuries, underperformance and finally just a lack of interest.

Jeff, however, was a rock in the lineup and in the field. He batted .289 with 29 homers. He also scored and drove in more than 100 runs. The rest of the Dodger infield was a shambles, with a revolving door at third, a career-threatening injury to shortstop Cesar Izturis, and a rogue’s gallery at first led by Hee Seop Choi and Olmedo Saenz. Jeff volunteered to play first to open up his position to a couple of promising kids, but the team told him to stay put. The Dodgers finished 71-91.

The 2006 club has been retooled with veterans like Nomar Garciaparra, Bill Mueller, Kenny Lofton and Rafael Furcal. Jeff fits right in with these names, and will no doubt anchor the lineup once again. If the team gets any pitching, and Eric Gagne returns to health, LA could challenge for a division title.

Jeff would certainly like to play in another World Series. It must have irked him to watch the Astros win the pennant the year after he left. Even if he does not get back to the Fall Classic, he will continue to creep closer to immortality. Indeed, if Jeff puts together a few more campaigns like '03, '04 and ’05, he should eventually earn serious consideration as a Hall of Fame candidate when he hangs up his spikes. What are his chances? Considering the position he plays, it could happen. But keep in mind that baseball writers have been known to hold a grudge, and the last time anyone looked Jeff was not a member of the all-interview team. He’ll have to continue clubbing the ball and breaking records for several more seasons.

What you need to know about Jeff is that, whether he makes it to Cooperstown or not, he would much rather play on a World Series winner. A self-centered jerk? Yeah, maybe. But anyone who calls him selfish should watch him hold his ground on a double play.

JEFF THE PLAYER

Jeff has established himself as one of the more dependable run producers in baseball, and he did so in PacBell Park, which isn't considered a great stadium for power hitters. Over the years, Jeff has proved to be more of a line-drive hitter who can drive the ball to all fields than a classic slugger—a style should serve him well in Houston.

Some say that Jeff owes much of his success in San Francisco to the presence of Barry Bonds in the lineup. While even he won't deny that he benefited from the way teams pitched around his former teammate, Jeff has shown more than once that he can carry a team when he's hot. In fact, it can be argued that Bonds would not have seen the pitches he did were it not for Jeff's emergence as a power threat.

Jeff won't be winning a Gold Glove anytime soon, but he has become a steady defensive player. His range is better than average, he has developed smoother hands and a more reliable throwing arm, and as mentioned, no second baseman hangs in tougher or longer when turning two.

The major rap against Jeff is his attitude. In his defense, he has always made it clear that he's not in baseball to make friends (yes, he does have a few), and face it—he did earn the respect of his teammates in San Francisco. In fact, many in the media felt his voice was the most important in the Giant clubhouse.