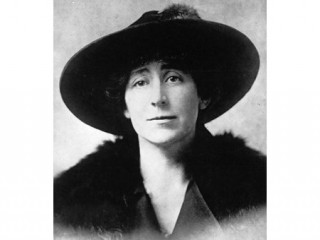

Jeannette Rankin biography

Date of birth : 1880-06-11

Date of death : 1973-05-18

Birthplace : Missoula, Montana Territory, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-07-20

Credited as : Politician, U.S.Senator,

Jeannette Rankin was born on a ranch near Missoula, Montana Territory, on June 11, 1880. She was the eldest of seven children of Olive Pickering, an elementary school teacher, and John Rankin, a successful rancher and lumber merchant. An indifferent student, she graduated from the University of Montana in 1902 with a B.S., but spent the next eight years casting about for a satisfying vocation. She taught school briefly, apprenticed as a seamstress, learned furniture design, and became a social worker. To qualify herself for social work, she studied at the New York School of Philanthropy in 1908 and briefly practiced in Montana and Washington state. However, feeling suffocated by social work, she quit and enrolled in the University of Washington. While a student she became involved in the successful 1910 campaign for women's suffrage in Washington, which proved to be a decisive event in her life. She became a suffrage worker, which led directly to her career as a social reformer and peace advocate.

Returning to Missoula for Christmas, Rankin learned that a suffrage amendment was being introduced in the Montana legislature in the session beginning January 1911. She quickly organized the Equal Franchise Society, asked to address the legislature on suffrage, and became the first woman to speak before the Montana legislature. Although the amendment narrowly failed, Jeannette Rankin had been launched on a political career. The national suffrage leaders noticed her, and in the next five years she was constantly involved in suffrage efforts across the nation, especially after becoming a field secretary for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). She was the driving force in the victorious Montana campaign in 1914, and the experience helped her to decide to run for Congress in 1916.

Montana had two congressional seats elected at large. Rankin always maintained that this arrangement made possible what seemed impossible for a woman in 1916. In the Republican primary she captured one of the two places on the ticket, far outdistancing the seven men who ran. She carried the women's vote and seemed to be the second choice of everyone else. Running at large in the general election also favored her as she had become one of the best known figures in the state. She campaigned for national woman suffrage, prohibition, child welfare reform, tariff revision, and staying out of World War I in Europe. But before she could take her seat in Congress Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare and Wilson decided to ask Congress for a declaration of war.

She took her seat in the House of Representatives on April 2, 1917, and four days later voted against war with Germany. Fifty-six other members of Congress also voted against war, but her vote spoke the loudest: she was the first woman in Congress. She had evolved a peace position during her suffrage days. The leadership of the woman suffrage movement, social work, and child welfare campaigns had many women, such as Jane Addams, who were pacifists, and they helped to shape Rankin's views. Ironically, most of her suffrage friends urged her to vote for war. Carrie Chapman Catt, head of NAWSA, feared that Rankin's vote would damage the suffrage cause by seeming to prove that women were sentimental and irresponsible.

Rankin saw herself as the women's representative, and she pressed the social feminist agenda of suffrage, equal pay, child welfare, protection of working women, birth control, infancy and maternity protection, and independent citizenship. (A 1907 law stripped citizenship from American women who married aliens.) Although she voted for a later declaration of war on Austria-Hungary and for war expenditures and Liberty Bonds, her first anti-war vote eroded her support in Montana. In addition, she sided with the miners in a bitter struggle with the Anaconda Copper Company in 1917. The company-dominated legislature then divided the state into separate congressional districts and gerrymandered Rankin's district so that it was overwhelmingly Democratic. Seeing little chance to retain her seat in the House of Representatives in 1918, she ran for the Senate instead. Losing in the Republican primary, she then ran a hopeless race in the general election on a third party ticket. After leaving Congress she was a delegate with Jane Addams and other peace activists to the 1919 Women's International Conference for Permanent Peace. Out of this came the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), and Rankin was named vice-chair-woman of its executive committee.

After her duties abroad she returned to the United States to become a field secretary for the National Consumers' League (NCL) under the direction of Florence Kelley. As such, she lobbied in Washington, D.C., for many of the reform measures that she had introduced in Congress. In 1921 she helped to bring about the passage of the Maternity and Infancy Protection Act, a bill that she had first introduced in 1918. She saw independent citizenship approved in 1922, and she worked to get the Child Labor Amendment passed in 1924. That autumn she resigned from the Consumers' League position to aid her brother's unsuccessful bid for the Senate. She could not know it, but her greatest accomplishments had all been made and her greatest frustrations were yet to come. Her energies, which had encompassed the broad range of social feminist reform, increasingly narrowed to the peace movement.

Discouraged with the militarism of Montana, she made a second home in Georgia, which she naively thought would be more receptive and responsive to her peace crusade. She organized the Georgia Peace Society in 1928 and tried to make Georgia a center of the peace effort, but she was to be sorely disappointed. She became a field secretary for the WILPF, but resigned within a year over disagreements with the national staff.

In April 1929 she became a paid lobbyist of the Women's Peace Union, a group trying to get a constitutional amendment to outlaw war, but soon resigned because of disagreements with the leadership. The National Council for the Prevention of War (NCPW) immediately engaged her as a Washington lobbyist. She remained with the NCPW from 1929 to 1939, resigning finally out of exasperation with the NCPW chairman and in disagreement with its tactics. In the 1930s she worked for the anti-war amendment, fought Navy appropriations, lobbied for U.S. adherence to the World Court, supported the neutrality laws, and whole-heartedly embraced the "devil theory of war," the view that the United States had been dragged into World War I by the "merchants of death"—the bankers and munitions makers.

By the mid-1930s the guns of war had begun in China, Africa, and Spain. Rankin could see no justification for the United States to intervene in foreign wars, and she came to believe that President Franklin Roosevelt was plotting involvement. She strongly supported the America First Committee, and her passion for peace blinded her to the character of the likes of Father Charles Coughlin because he, too, opposed involvement. As the world slid into war, she concluded that lobbying efforts were ineffective, so she returned to Montana and ran for Congress in 1940.

Despite having been absent from Montana's political scene for 15 years, she won as a Republican pledged to keep America out of the war. In Congress, she fought a losing battle against military appropriations, the draft, and the war itself. This time, she stood alone, casting the only vote against the declaration of war against Japan after Pearl Harbor. She was the only person to have voted against war in 1917 and 1941, and the second time she experienced almost universal condemnation. Her political career was finished. She came to believe that Roosevelt deliberately provoked the Japanese attack.

From 1942 to 1968 she disappeared from the public's view. She travelled and tended to family affairs, but she was so forgotten that most people did not know that she was still alive. A reprise came during the Vietnam War when the leaders of the Women's Strike for Peace asked her to head the procession in the Jeannette Rankin Brigade in their march on Washington. Nearly 88 years old, she marched at the head and presented the women's petitions to the House and Senate leadership. In the following years she took part in many peace demonstrations, and, having regained the public's attention, she advanced her ideas about peace, preferential presidential elections, a unicameral Congress, and representation-at-large. She died in her sleep on May 18, 1973, almost 93 years old.