Jason Williams biography

Date of birth : 1975-11-18

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Belle, West Virginia, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-06

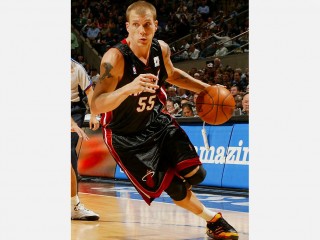

Credited as : Basketball player NBA, currently plays for the Miami Heat,

0 votes so far

It is not often that a guy like Jason Williams gets the last laugh. A combustible mix of high-maintenance personality and hi-test talent, he went through schools, teams and coaches faster than halfcourt traps—until he found love and success in Miami. For most of his hoops career, Jason embodied one of basketball’s most perplexing questions: Why make the easy play when you can spin 360 degrees and throw a behind-the-back no-look pass? Why indeed. Known to some as the Hip-Hop Pete Maravich but to most as White Chocolate, Jason has been called a lot of other things over the years, but few that can printed here. Now he can finally answer to "champion."

GROWING UP

Jason Chandler Williams was born on November 18, 1975 in Belle, West Virginia. The family lived in a trailer on the grounds of DuPont High School. Jason's father, Terry, was a state trooper, and had the keys to the gym. Jason took advantage of this fortunate circumstance whenever possible.

The youngster showed an early flair for basketball. At age four, Jason was already an accomplished ballhandler, and by age seven he had determined that he would become an NBA player some day. Jason was gifted in every sport he tried. He pitched in sandlot baseball games, and played quarterback on the same fields come the fall. Eventually, Jason became a first-rate football player.

A natural athlete with confidence and cockiness to match his considerable skills, he excelled in pushing adults’ buttons. (In fact, he has admitted taking a special delight in testing the patience of authority figures.) Jason’s brother, Sean—a straight arrow by comparison—recalls him constantly coming home 15 minutes past curfew, just to see his parents’ reaction. Jason was also a habitual hooky-player. These personality traits would catch up with him later in life.

Jason became the star of the DuPont basketball team in 1990-91, his freshman year. As a junior and senior, he teamed up with classmate Randy Moss for some memorable alley-oops. Moss had his own issues with authority, but he and Jason became good friends, and they drew hundreds of fans on game nights, forcing the school to install temporary bleachers to accommodate the overflow crowds.On the gridiron, it was the same story—Jason passed and Moss caught, and DuPont proved a formidable opponent during the 1992 and 1993 seasons.

At the end of the 1993-94 season, Jason was named USA Today West Virginia Player of the Year, capping off a stellar senior campaign with an 18-point, 10-assist average. He and Moss took DuPont to the state championship game, where they lost. Still, Jason became the only player in school history to net more than 1,000 career points. He also handed out more than 500 assists in four varsity seasons.

College recruiters were flocking to tiny Belle by this time, but Jason had some academic hurdles to negotiate before he could play college ball. He had also developed a liking for marijuana, which would come back to haunt him in college and the NBA.

Jason originally committed to play ball for Providence, feeling he had connected with coach Rick Barnes. But when Barnes left for Clemson, Jason wriggled out of his deal. That fall, he enrolled in Fork Union Military Academy in Virginia, a basketball breeding ground known for preparing young athletes for the rigors of college academics. That idea lasted all of three days. When Jason was handed a pop vocabulary quiz with 300 words on it, he had seen enough.

Jason’s dad suggested he explore the possibilities at Division-II Marshall in West Virginia. He had met Billy Donovan there and was impressed by the young coach, who offered Jason a chance to play after red-shirting the 1994-95 season. During 1995-96, the freshman—now 20—averaged 13.4 points and 6.4 assists for the Thundering Herd.

ON THE RISE

After Donovan accepted a job at the University of Florida, Jason decided to follow him there. He sat out the 1996-97 season as a transfer, practicing with the team and ostensibly concentrating on his studies. But the book work bored Jason and he retreated back to West Virginia. His father stepped in again and convinced him to stick it out.

In 1997-98. Jaosn won the starting point guard job for the Gators and played brilliantly, averaging 17.1 points and 6.7 assists against top-flight college competition. His darting, spinning drives, reckless penetration and impossible behind-the-back passes, majestic three-pointers, and uncanny showmanship brought fans out of their seats again and again—even in enemy arenas. Many compared him to another SEC legend, Pete Maravich. Jason was the hottest thing in college ball. Then he was caught using marijuana and kicked off the team after 20 games.

College just wasn’t for Jason. He was a basketball player, and he was tired of pretending that he was in school to get an education. That spring, at age 22, he declared himself eligible for the NBA Draft.

Most pro teams refused to consider Jason. The Sacramento Kings, lacking pizzazz and in search of a point guard, overlooked his faults and snagged him with the seventh overall pick.

Jason went through a difficult rookie year under disciplinarian Rick Adelman. He was homesick for West Virginia, and also uncomfortable being Sacramento’s most recognized athlete. Sometimes he felt that his life was not his own. Welcome to pro sports.

Despite his difficult adjustment to life in the NBA, Jason led the team with 299 assists in the truncated 1999 season, and the Kings finished with a decent 27-23 record. Sacramento's year ended in the playoffs with a 99-92 overtime loss to Utah Jazz in the deciding game of the first round.

The NBA marketing machine embraced Jason, and he reciprocated with nightly highlight-reel material. His nickname, “White Chocolate,” became one of the league’s most widely known. His jerseys sold like crazy, and the behind-the-back pass enjoyed a revival throughout the NBA.

Jason played two more season with the Kings, forming the team’s nucleus along with Chris Webber, Peja Stojakovic and Vlade Divac. Sacramento won 44 games in 1999-2000, but bowed to the Los Angeles Lakers in the first round of the playoffs. In 2000-01, the Kings won 55 times. Newcomer Doug Christie gave the team a defensive stopper, and reserves Scot Pollard and Bobby Jackson contributed to a sparkling bench. Jason was good for around 10 points and seven assists a night during his three years as a King, but for all his talent, he was viewed as erratic and unreliable from game to game.

Sacramento desperately wanted to win a championship, and eventually the brass just felt they could not do so with Jason at the helm. The tipping point came early in the '00-01 season, when Jason was suspended for five games after testing positive for marijuana. Making obscene gestures and comments to the fans, as well as insensitive remarks about Asians and gays, cost him $25,000 in fines from the league, and punched his ticket out of town. After the season, the Kings sent him to the Vancouver Grizzlies in a deal for Mike Bibby. Jason moved that fall with the rest of the club to Memphis, where they remained the Grizzlies.

There were more ups and downs in Memphis, but Jason played decent ball for Sidney Lowe, usually in a losing cause. In 2001-02, he averaged a career-high 14.8 points and added eight assists per game. His top performance came early in the year when scored a career-high 38 against the Houston Rockets.

Midway through Jason’s second season for Memphis, Hubie Brown took over as coach. As a TV analyst, Brown had frequently criticized Jason’s play. Although their relationship started off cordially, it eventually turned toxic. While Brown gave his point guard an extended leash, his son, Brendan—a Grizzlies assistant—clashed often with Jason. By 2003-04, the former lottery pick was seeing extended bench time. His frustration eventually boiled over in an ugly shouting match with the younger Brown during a televised game. GM Jerry West realized he had to find Jason a new home.

Brown, however, left before Jason, retiring early in the 2004-05 season because of health concerns. New coach Mike Fratello didn’t get along any better with Jason. The last straw was a pen-snatching confrontation in the lockerroom between Jason and a Memphis sports columnist that was caught on videotape.

MAKING HIS MARK

By this time Jason no longer coveted the attention of an NBA star. It had caused him nothing but frustration and trouble, much of it his own doing. When he heard rumors of a trade to the Celtics, he winced, realizing that he would be expected to entertain the crowd in the Boston Garden while the team rebuilt. Jason’s eyes lit up, however, when talks with the Miami Heat were mentioned. Playing a support role to Shaquille O’Neal and Dwyane Wade—and reasserting his basketball skills as an off-the-bench player on an up-and-coming squad—sounded like the perfect next chapter of his NBA career.

Ironically, Shaq had been trying to get Jason on his team for many years. The two had become friends and neighbors in Orlando, after their initial meeting at the 1998 draft. Jason talked his way into a pickup game that included O'Neal and Penny Hardaway. In one of those legendary streetball moments, Jason destroyed Hardaway one-on-one in front of a roaring crowd. (Shaq still compares the scene to something out of White Men Can't Jump.) When the hulking center played for the Lakers, he constantly pestered West, LA's GM at the the time, to snatch Jason off the Sacramento roster. Later, after joinging the Heat, he asked Pat Riley to acquire him.

Miami agreed to the deal on August 2, 2005 as part of a five-team, 11-player trade that also brought James Posey to the Heat. For Williams, it was a time to begin anew. He showed up in Miami the next day with a box of pens to hand out to reporters, spoofing the incident in Memphis the previous season. He promised to play his game and stay out of the limelight, and made good at that promise, staying out of trouble, alternating with Gary Payton at the point, and getting the ball to Wade and O’Neal. In his part-time role, he averaged 4.9 assists and 12.3 points.

Jason went into the playoffs fresh after being sidelined the final eight games of the regular season with tendonitis in his right knee. Riley used him judiciously during the postseason, and he contributed to the cause in every game, as Miami cruised through four series to win its first NBA crown. Jason averaged 9.3 points and 3.9 assists, and played with terrific consistency in series wins over the Chicago Bulls, New Jersey Nets, Detroit Pistons and dallas Mavericks. To go from the trash heap to the pinnacle of basketball in one season was something not even he could have imagined. The fact that a couple of other oft-maligned veterans—Payton and Antoine Walker—joined him on this journey just made it even sweeter.

Although Jason will never be crowned Mr. Consistency, those who have known him over the years will attest to his one unwavering goal—no matter where Jason was on the pro Richter Scale, no matter how erratic his game or demeanor, since the day he first set foot on NBA hardwood, he has wanted just one thing: a championship ring. Now, of course, he wants another.

JASON THE PLAYER

Though still an erratic player, Jason has settled down since his early years in the league. During that time, he has learned to keep it simple—especially when he has an open three-pointer or a clear passing lane to O’Neal or Wade. With Pat Riley's emphasis on the fundamentals, Jason seems to understand better that an assist counts just the same if it's a two-handed chest pass.

That's not to say Jason has changed completely. He remains a showman at heart, but can now pick his spots more judiciously in the Miami offense. As a veteran player, Jason is usually on the floor at crunch time. He makes his free throws and can hit clutch shots from long range. He is also a good penetrate-and-pass man.

On defense, Jason must make up for his relatively small size with quickness and anticipation. His commitment to defense is not exactly unwavering, even under Riley, who values this highly in his role players.