Jaromir Jagr biography

Date of birth : 1972-02-15

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Kladno, Czechoslovakia

Nationality : Czech

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-07-29

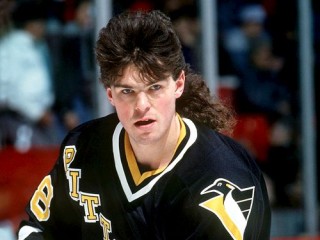

Credited as : NHL Ice hockey player, played for the Penguins,

2 votes so far

GROWING UP

Jaromir Jagr was born on February 15, 1972, in Kladno, Czechoslovakia, an ancient town of 80,000 in central Bohemia. He has one sister, Jitka. Jaromir’s father—also named Jaromir— was a mine administrator. It was a hard job with much responsibility. The pay was better than most workers, but the family could not afford any luxuries, and there weren’t many luxuries available anyway. Jaromir remembers waiting in long lines for many of the things that Americans take for granted, like fresh fruit, bread, meat, and toilet paper.

Most Czechs simply accepted this way of life, but the Jagrs harbored deep resentment against the Communist government. Jaromir’s grandparents had been wealthy landowners prior to World War II. When the Russians took over in 1945 and the country went Communist three years later, they were stripped of their property and allowed to stay in their farmhouse, but without their farm. When his grandfather (yes, also named Jaromir) refused to work his former land for free, he was jailed for two years. The elder Jagr passed away during the 1968 Prague Spring uprising, which was later crushed by Russian tanks. Jaromir is proud that his grandfather died a free Czech.

As a youngster, Jaromir hated living under the yoke of Communism. His heroes were Martina Navratilova, who had defected from Czechoslovakia to the U.S., and Ronald Reagan who vowed to bring the USSR to its knees. He carried a picture of the president around in his wallet. Jaromir frequently scratched the number 68 into his hockey helmet to commemorate the 1968 Czech revolution, and later adopted it as his uniform number.

Jaromir started skating around the age of three. He learned to shoot in his backyard, playing street hockey with his dad. He often took 500 shots a day. At age six, he was on three different teams, which meant he got triple the ice team of other kids. His stickhandling and shooting skills were superb, but he was just an average skater. When he heard that the country’s top players improved their speed by doing squats, he started doing 1,000 a day. Within a year he was the fastest player on his team.

By the age of 12, Jaromir was one of the best young players in the country. He began his junior hockey career playing against boys five and six years older. In his first year for Kladno’s junior squad, Jaromir scored 24 goals in 34 games. In 1985, he attended the World Championships in Prague as a fan. Mesmerized by a young Canadian star named Mario Lemieux, he thus began his dream of making it to the NHL one day.

Jaromir played three more seasons of junior hockey, and by the time he 16 it was getting ridiculous. He had grown to six feet tall and outweighed the other boys by 20 or 30 pounds. He was a smooth, natural skater who was too fast to shadow and impossible to knock off the puck. He skated around defensemen like they were fire hydrants.

Jaromir scored 57 times in 35 games in 1987-88, earning a promotion to the Czech national team as its youngest player. Within a season, he was the country’s top star, outperforming the likes of future NHLers Bobby Holik and Robert Reichel. He was also making more money than his dad, which was kind of cool.

Early in 1990, Jaromir and his countrymen squared off against Canada in the World Championships, facing the likes of Paul Coffey and Steve Yzerman—and beat them. That is when he knew he was good enough to be an NHL star.

Jaromir’s ascent happened to coincide with the fall of Communism in Czechoslovakia, removing the barrier that kept Czech players out of the NHL. Prior to this time, Eastern Bloc stars wishing to play in America had to defect, leaving their friends, families and countries forever.

With the permission of the new government, the top Czech players made themselves available in the draft. The Pittsburgh Penguins selected Jaromir with the fifth pick in the 1990 draft, and threw him right into the fire.

Jaromir joined a team that had all the ingredients needed to compete for the Stanley Cup, except the health of their top player, Lemieux. Super Mario had missed 21 games in 1989-90—just enough to keep Pittsburgh out of the playoffs. Now it was announced that his aching back would likely keep him out until the spring. The Penguins had assembled an excellent but expensive group to support Lemieux—Paul Coffey, Bryan Trottier, Jiri Hrdina, Joe Mullen, Tom Barrasso, Ron Francis, Larry Murphy, and talented youngsters like Jaromir , Kevin Stevens and Mark Recchi. Now they had to decide whether to sell off their high-priced stars, or let them play together in anticipation of Lemieux’s return.

To their credit, coach Bob Johnson and team execs Scotty Bowman and Craig Patrick decided to let the healthy players learn to win on their own, and kept their fingers crossed that Mario would turn a good team into a great one when he returned. He ended up appearing in 26 games at season’s end—just enough to get his timing back.

ON THE RISE

During this time, Jaromir watched everything Lemieux did. He watched how he used his body and his mind, and how he could dictate the flow of a game just by being on the ice. When Jaromir encountered a new or confusing situation, he asked himself WWMD—what would Mario do? If he wasn’t sure, he would ask his teammate, who was more than willing to pass along any wisdom he could. The result of this relationship was that Jaromir started to sense when the team needed him to step up and take charge, and when it was smarter to hang back and simply be a contributor.

The moment Pittsburgh fans saw Jaromir and Mario on the ice at the same time, they knew there was a chance something special would happen. Both players moved their hulking bodies around the ice with speed and grace, and both had superb vision. Jaromir’s first instinct was always to pass—not uncommon for European players coming to the NHL—but he also demonstrated a scoring touch, particularly with his wrist shot from the slot. He showed nice ability to shoot on the fly, too.

Jaromir knew how to handle the media as well. His English was poor, so he was spared the impromptu post-game press conferences to which Lemieux was subjected, but he charmed reporters with his boyish enthusiasm, and practical jokes. He enjoyed nothing more than joining the throngs in front of Mario’s locker, asking a question in broken English, and shoving a banana in his teammate’s face as he awaited an answer. Jaromir also volunteered to read the weather on a local morning radio show, and was hilarious. Basically, he was completely unintimidated by the pressures of being the next big thing.

Jaromir was not intimidated by NHL defensemen, either. He was strong enough to get to the net with a blueliner draped over his back, and relished digging for pucks along the boards. Though Jaromir had a lot to learn on defense, the Penguins were not overly concerned—he had both the ability and intelligence to improve this part of his game. His final numbers for 1990-91 barely hinted at his overall abilities, but they were excellent nonetheless—27 goals, 30 assists and a scoring percentage of 19.9—especially considering he was the youngest player in the league.

The Penguins finished 41-33-6, good for first place in the Patrick Division. They opened the playoffs with a loss at home to the New Jersey Devils, but rebounded to win the series four games to three. Jaromir, who tallied 37 of his 57 points in the season’s final 40 games, scored the series-winner in overtime. Pittsburgh disposed of the Washington Capitals easily in the division finals, but dropped the first two games of the conference finals to the Bruins in Boston. The Penguins regrouped and ran the table on Boston to reach the Stanley Cup Finals for the first time in team history.

The finals pitted the Pens against the surprising Minnesota North Stars, who fashioned a two-games-to-one lead before Lemieux almost singlehandedly won the next three games and the championship. Jaromir had five assists in the finals to set a rookie record.

Jaromir and his teammates had little time for rejoicing. Coach Johnson was diagnosed with brain cancer after the playoffs and died that summer. Repeating in the NHL is hard enough, doing so after the death of your leader seemed impossible. The decision was made to stay within the Penguin family, with Bowman returning to the bench to take over the club. He was a stern taskmaster, and the players bristled under his iron hand.

Jaromir did not enjoy the frequent tongue-lashings he received, but produced a good season for the Pens, who pulled together down the stretch and secured a playoff spot with a third-place finish. The second-year winger notched 32 goals and 37 assists in 70 games. A moderately healthy Lemieux and the late-season additions of sniper Rick Tocchet and enforcer Kjell Samulesson made Pittsburgh a formidable post-season team once again.

The Penguins faced elimination in the first round, defeating Washington in seven games after dropping the first two contests. Another tough series awaited them in the second round, as the Rangers pushed them to six games, and cracked Lemieux’s wrist in the process. Once again, Jaromir stepped up, scoring the series-winner against New York.

Pittsburgh got a reprieve in the conference finals, sweeping Boston in four straight to earn a berth in the Stanley Cup Finals, this time against the Chicago Blackhawks. The Penguins were rolling at this point, and they swept Chicago in four very tight games.

Jaromir proved his mettle in his second post-season, scoring 11 goals and garnering 13 assists is 21 games. Four of those goals were game-winners—including three in a row after Lemieux broke his wrist. He was the dominant player in the Ranger and Bruin series, and scored the prettiest goal of the post-season in Game 1 of the Finals against Chicago. With five minutes left and the Pens trailing 4-3, he collected the puck in the corner, deked his way past three Blackhawk defensemen and tucked a backhand past a shocked Eddie Belfour. Lemieux then scored the game-winner with 13 seconds left.

Over the next six years, the Penguins won their division four times and finished second twice. They failed to return to the Stanley Cup Finals, however, and reached the conference finals only once, in 1996. Although an NHL title eluded Pittsburgh during these seasons, they will always be remembered as the “Jagr Years,” when Jaromir blossomed into hockey’s greatest scoring threat.

The ascent began in 1992-93, when he reached the 30-goal plateau once again, but increased his assists to 60 to finish with 94 points. This despite the fact that his shooting was erratic, he was often double-teamed, and the league’s goons were having their way with him. In a devastating playoff loss to the Islanders, Jaromir let himself get intimated by the New York players, which may have cost the Pens a shot at a third straight Stanley Cup.

Jaromir was forced to become more of a leader in 1993-94, when Lemieux missed all but 22 games. He was frequently double-shifted, and did not mind the extra responsibility. He led the team with 67 assists and once again scored over 30 goals. At age 22, he was generally considered the best one-on-one player in the league.

The strike-shortened season of 1994-95 served as an abbreviated coming-out party for Jaromir. With Lemieux battling a bad back and Hodgkin Disease, it fell to Jaromir to shoulder the burden of superstardom a year or two before the team would have liked. He responded magnificently, winning the Art Ross Trophy with a league-best 70 points in 48 games. His 32 goals ranked second in the NHL, and he was a finalist for the Hart Trophy as MVP.The Penguins finished with 29 victories, third most in the NHL. Jaromir netted 10 goals in 12 playoff games, but Pittsburgh bowed out in the second round.

The difference in Jaromir’s game was obvious, even to the casual observer. His skating was flawless, and he had finally learned how to use his massive 6-2, 210-pound body to his advantage. He stayed low and centered over his skates, making it almost impossible to knock him off the puck. His footwork was magical, and his stickhandling unrivaled. With defensive wiz Ron Francis centering for him in place of Lemieux, Jaromir was free to make more rushes and take more chances from the right wing.

Pittsburgh fans could hardly wait to see what their young Czech hero would do over a full schedule—particularly when it was announced that Lemieux had returned to full health.

The 1995-96 season was a magical one for the two Pittsburgh stars. Mario scored 69 goals and had 92 assists to win the Art Ross Trophy for the fifth time. Jaromir scored 62 goals and dished out 87 assists to finish second to his teammate in the scoring race with 149 points. Their offensive dominance was total—the third-place finisher, Joe Sakic, had 120 points—41 behind Lemieux and 29 behind Jaromir. But it was Sakic who got the last laugh, as his Colorado Avalanche captured the Cup that spring.

MAKING HIS MARK

With his great year, Jaromir established himself as one of the great right wings of all-time. No one at the position had scored more goals in a season or tallied more points. He was no longer bashful about shooting, leading the league with 403 shots on goal. He was also the only Penguin to skate in all 82 games. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this season is that Jaromir played on a different line than Lemieux, meaning Pittsburgh opponents had to deal with a scoring machine on the ice for the majority of time during a game. Coach Eddie Johnston decided to keep Jaromir on the line with Francis and newcomer Petr Nedved, a creative player who owned the NHL’s deadliest wrist shot.

Infused with confidence, Jaromir no longer let teams distract him with big hits. He did not invite contact, but was not afraid to absorb a hard check. Besides, as the league’s most talented skater, he made a difficult target in the open ice. Shadowing him made no sense, either. When a defender got close to him, he would take two long strides and be gone—usually creating an odd-man situation and another scoring opportunity for the Pens.

The 1996-97 season was shaping up as a repeat until a groin injury sidelined Jaromir for 19 games. The condition started with a poorly fitted skate on his right foot, and worsened as he tried to play through it. Jaromir still finished among the league leaders in goals, assists and points, finding the net 47 times and totaling 95 points. After the season, Lemieux—who won the scoring title yet again—announced that he would be retiring.

All eyes were on Jaromir in 1997-98, as he was now officially the MAN in Pittsburgh. With opponents now stacking their defenses against the Jagr-Francis-Nedved line—and with Jaromir still smarting from a sore groin—he delivered a super season with 35 goals and a league-high 67 assists.

That winter, Jaromir led the Czech Republic to the gold medal at the Olympics in Nagano, scoring one goal and four assists. The final victory was especially sweet for Jaromir, as it came over the hated Russians. When the team returned to Prague, 100,000 fans jammed into Wenceslas Square to cheer them. It was the highlight of Jaromir’s life.

Upon his return, the Penguins won the Northeast Division, and Jaromir claimed his second Art Ross Trophy. He topped the NHL with 38 power-play points and paced the Pens in goals, game-winners, and plus-minus. Once again, he was a finalist for the Hart Trophy, this time losing to Dominik Hasek.

Despite a career-defining performance, Jaromir was not a happy camper. The team’s coach, Kevin Constantine, was a taskmaster who advocated shooting the puck into into the offensive end and chasing after it—an approach Jaromir never appreciated and railed against both publicly and privately. Despite signing a lucrative six-year extension, he was now thinking he wanted out of Pittsburgh. When Francis signed a free agent deal with the Carolina Hurricanes during the summer, Jaromir could think of little reason to stay with the Penguins.

But stay he did, and despite a shoddy supporting cast, he turned in one of the best seasons in recent memory. He played his heart out, tweaked his game to suit his new linemates, and skated off with the Hart Trophy as league MVP. Jaromir won the scoring title by 20 points, with 44 goals and 83 assists. He also captured the 1998-99 Lester Patrick Award, the MVP as chosen by his fellow players.

Jaromir unveiled a new slap shot in 1999-00 and repeated as NHL scoring champ, despite missing a quarter of the season to various pulls and strains in his legs and back. He tallied 42 goals and 54 assists for 96 points in a league that was featuring more and more neutral zone traps and other alignments meant to choke off scoring. Had the Penguins provided him with a couple of top-flight linemates, and had he remained healthy, Jaromir could have legitimately outscored every other NHL player by 30 or 40 points. He was now that good.

It came as little surprise when Jaromir won his fourth straight scoring title in 2000-01, with 52 goals and a league-best 69 assists for 121 points. He started strong and finished even stronger, earning NHL Player of the Month honors in both November and March. He scored his 400th goal and 1,000th point during the campaign, and also played in his 800th NHL game. Although the Penguins finished third in the division, they reached the conference finals for the first time since 1996, falling to the Devils in their quest for a berth in the Stanley Cup Finals.

On July 11th, the Penguins traded Jaromir to Washington. He was due to sign a new contract, and Pittsburgh knew it would not be able to afford him, so they got what they could when they could. The Caps had an impressive conglomeration of NHL talent, but lacked that one great star who could dominate games and dictate play. If one person in hockey fit that description, it was Jaromir. Washington signed him to a $77 million contract, which helped nail down the team’s first ever full-season TV deal.

The Capitals needed a veteran superstar and Jaromir certainly filled the bill. Physically, he was everything you could ask of a player. He could put the puck in the net 50 different ways, he was still the league’s top skater, and he had added 20 pounds of hardened muscles since his early days in Pittsburgh. Jaromir had legs like tree trunks, and a rear end that he actually used as a weapon, inviting contact and then spinning defenders off him, a la Charles Barkley.

Mentally, however, Jaromir was not all the Caps had anticipated. Knowing what was expected of him, Jaromir tried to do everything, all at once, on every shift. He ended up accomplishing nothing. Washington played a dump and follow style that was unlike anything he had experienced in Pittsburgh, where a premium was placed on slick skating and passing. Disappointed, Jaromir played indifferently on a line with hatchet-man Chris Simon and Dainius Zubrus, a converted right wing.

Jaromir picked up the pace after the Olympic break, finishing fifth in the NHL with 79 points. The Caps failed to secure a playoff berth, however, leaving Jaromir out of the post-season for the first time in his career.

The 2002-03 season saw Jaromir reunite with a couple of pals from Pittsburgh—Robert Lang and Kip Miller. Miller, a journeyman left wing, had his most productive seasons when he got to play on Jaromir’s line, and the two clicked again in Washington. Lang, meanwhile, roomed with Jaromir on the road. With this added comfort factor—and the departure of Adam Oates (top dog on the team when Jaromir arrived)—Jaromir was a little happier. But it still irked him that Russian winger Petr Bondra was the favorite of the fans.

All in all, it was another down year. Despite leading the team with 36 goals and 77 points, Jaromir nearly dropped out of the Top 20 in scoring for the first time. The highlight of the season came in a game against his former teammates, when scored three goals and tallied four assists versus the Penguins in December. The Caps had a decent year, finishing second in the Southeast Division, but they made an early playoff exit against the Tampa Bay Lightning. Jaromir, bothered by a sore wrist, scored just two goals in the series.

Two years after being hailed as one of history’s greatest players, Jaromir had become an indifferent and ordinary ex-superstar. This made him instantly appealing to the Rangers, a club that had waited 54 years for a Stanley Cup, then spent the next decade recycling glitzy fading stars for its corporate ticket holders, while alienating its hardcore fans. The price was right—Anson Carter—and Washington and New York made the swap halfway through the 2003-04 season. Jaromir registered his 12th consecutive 30-goal, 70-point campaign, but did little to prevent the Rangers from missing the playoffs for the seventh year in a row. The team won just nine of the 34 games in which he suited up, and GM Glen Sather housecleaned 10 veterans at the trading deadline.

The 2004-05 season was lost to a lockout. For veterans like Jaromir, the time off was either a blessing or a curse. Some felt that they were losing a year they would never get back. In Jaromir’s case, it enabled him to rediscover his passion for hockey. He played 17 games for Kladno in the Czech Republic and score 28 points. From there, he joined a Russian team in the Super League, and led all scorers with 13 points in 11 games. Jaromir finished his “year off” by leading the Czech national team to a gold medal at the World Championship.

Hockey was fun again. Jaromir concentrated on feeding his teammates and making them better, and they in turn stepped up their games. When the labor dispute was settled in the summer of '05, Jaromir could not wait to return to the NHL. The Rangers, knowing their star played better when he was happy, brought in countrymen and Olympic teammates Martin Straka, Marek Malik, Martin Rucinsky and Petr Sykora, as well as Czech rookie Petr Prucha. Jagr teamed with Straka and Michael Nylander, and quickly reestablished himself as one of the NHL’s most formidable offensive weapons.

New York, picked by most pre-season publications as the worst team in the division, was challenging for the division lead at the mid-season mark, and owned one of the 10 best records in the NHL. They were playing solid hockey at home, great on the road, and were doing it with a mix of young, hungry players and hard-working veterans. For his part, Jaromir was among the league leaders in just about every major offensive category, and was averaging a point and a half per game.

Jaromir’s job is to fill the shoes of Mark Messier, the legendary Ranger who announced his retirement during the lockout. That means more than contributing goals. It requires some leadership plus a certain flair for the dramatic.

Perhaps it was a sign of things to come when, on the night of Messier’s emotional retirement at Madison Square Garden, Jaromir drilled the overtime game-winner against Mess’s old team, the Edmonton Oilers.

With the blue shirts aching for a post-season berth, and some wiggle room under the cap ahead, the second coming of Jaromir Jagr may soon be the hottest ticket on Broadway.

JAROMIR THE PLAYER

Although he has lost a bit of the explosiveness he had in his 20s, Jaromir is still the best skater in the NHL. He is fast, powerful and tricky with his feet and stickwork. No one moves the puck from the backhand to the forehand faster, and no one is as hard to control in the open ice. His long reach enables him to put the puck on a yo-yo, tricking unwary defensemen into swiping at the biscuit before he skates past them.

Jaromir is the very definition of an NHL sharpshooter. When the puck is on his stick, he is aware of every twitch a goaltender makes, and every inch a defenseman is out of position. He can fire the puck through the slimmest openings, sometimes even anticipating holes that are a second or two away from developing.

Jaromir can squeeze off wrist shots, slap shots and one-timers as well as anyone in the league, and he brings a scorer’s mentality to the ice. After his year off, he rediscovered the pleasures of passing, and has reminded everyone how much better he can make teammates when playing unselfishly.

Jaromir’s defense has never been good, but he is an important man on the penalty kill because of his size, strength and ability to score shorthanded. He is murder on the power play, leading his team in power play goals almost every year.

Jaromir’s rock-star good looks and flashy European style grated on traditionalists when he first came into the NHL, and he certainly exhibits some diva-like qualities. Still, many fans appreciate his Original Six work ethic. He is never out of shape, rarely complains about injuries, and unlike his mentor Mario Lemieux, will not take a dive to draw a penalty.

EXTRAS

* The four players taken ahead of Jaromir in the 1990 draft were Owen Nolan, Petr Nedved, Keith Primeau and Mike Ricci.

* Jaromir scored his first hat trick in February of 1991 against the Bruins. He was the youngest Penguin in history to score three times in a game.

* In 1995, Jaromir became the first European-trained player to win the NHL scoring title. He was the first non-center since Guy Lafleur in 1977 to lead the league in points.

* Jaromir’s 149 points in 1995-96 broke the record for right wings, previously held by Mike Bossy.

* Jaromir scored 862 points during the 1990s. The only player to score more was Wayne Gretzky, with 878.

* In 2000, Jaromir became the first player ever to garner one million votes to the All-Star Game. He has been the leading vote-getter three times in all.

* In 1999-00, Jaromir became just the fifth player in history to win back-to-back Lester Pearson Awards.

* Jaromir lost the 2000 Hart Trophy balloting to Chris Pronger of St. Louis. It was the closest MVP race in history, 396 to 395.

* Jaromir’s league-leading 96 points in 1999-00 were the lowest total for an Art Ross winner in a full season since Stan Mikita led the NHL with 87 points in 1967-68.

* Jaromir had three assists in the 2003 All-Star Game.

* Jaromir credits John Leclair with showing him how to improve his one-timer.

* Jaromir’s sticks have been the subject of intense scrutiny since he came into the league. He orders them with an illegal curve, then planes them down to regulation. He has long been suspected of stocking un-planed sticks for special situations, but has yet to be caught. His curved sticks have contributed to one of his few flaws—an erratic backhand shot.

* Jaromir is less superstitious than most NHL players. He does, however, like to be the last person on his team to take the ice.

* Jaromir is a big tennis fan. His all-time favorite player is John McEnroe.

Jaromir’s favorite athlete is Pedro Martinez. He has been recording his starts since the 1990s.

* Jaromir’s father fashioned a set of weights for him from a tractor axle when he was a kid.

* Jaromir’s favorite pro sport to watch is NFL football.

* Jaromir’s 21st birthday in 1993 was carried live from a Pittsburgh nightclub on local radio.

* When Jaromir decided to cut his Euro-mullet in 1999, it made headlines all over the world.

* Jaromir had his own peanut butter brand when he played in Pittsburgh. The proceeds went to support local charities.

* When Jan Hrdina joined the Penguins, he and Jaromir were nicknamed the Czechmates.

* Jaromir’s favorite meal is chicken and mashed potatoes.

Jaromir was the only player to break the 100-point barrier in 1997-98.

* Jaromir opened the first sports bar in Prague.

* Jaromir insists that when he settles down, he will only consider marrying a Czech girl.

* Jaromir staked his father’s new business in the 1990s, and now he owns a chain of resort hotels.

* For many years while he played in Pittsburgh, Jaromir’s mother lived with him and kept house.

* When you rearrange the letters of Jaromir’s first name, you get Mario Jr.