Jan Vermeer biography

Date of birth : 1632-10-31

Date of death : 1675-12-16

Birthplace : Delft, Netherlands

Nationality : Dutch

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-10-31

Credited as : Artist painter, ,

2 votes so far

Early life

Delft, where Vermeer was born and spent his artistic career, was an active and prosperous place in the mid-17th century, its wealth based on its thriving Delftware factories, tapestry-weaving ateliers, and breweries. Within Delft's city walls were picturesque canals and a large market square, which was flanked by the imposing town hall and the soaring steeple of the Nieuwe Kerk (“New Church”). It was also a venerable city with a long and distinguished past. Delft's strong fortifications, city walls, and medieval gates had furnished defense for more than three centuries and, during the Dutch revolt against Spanish control, had provided refuge for William I, Prince of Orange, from 1572 until his death in 1584.

Vermeer was baptized in the Nieuwe Kerk. His father, Reynier Jansz, was a weaver who produced a fine satin fabric called caffa; he was also active as an art dealer. By 1641 the family was sufficiently prosperous to purchase a large house containing an inn, called the Mechelen, on the market square. Vermeer inherited both the inn and the art-dealing business upon his father's death in October 1652. By this time, however, Vermeer must have decided that he wanted to pursue a career as a painter.

In April 1653 Vermeer married Catherina Bolnes, a young Catholic woman from the so-called Papenhoek, or Papist's Corner, of Delft. This union led him to convert from the Protestant faith, in which he was raised, to Catholicism. Later in that decade, Vermeer and his wife moved into the house of the bride's mother, Maria Thins, who was a distant relative of the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert.

Artistic training and early influences

Surprisingly little is known about Vermeer's decision to become a painter. He registered as a master painter in the Delft Guild of Saint Luke on December 29, 1653, but the identity of his master(s), the nature of his training, and the period of his apprenticeship remain a mystery.

Since Vermeer's name is not mentioned in Delft archival records during the late 1640s or early 1650s, it is possible that, as with many aspiring Dutch artists, he traveled to Italy, France, or Flanders. He also may have trained in some other artistic centre in the Netherlands, perhaps Utrecht or Amsterdam. In Utrecht Vermeer would have met artists who were immersed in the boldly expressive traditions of Caravaggio, among them Gerrit van Honthorst. In Amsterdam he would have encountered the impact of Rembrandt van Rijn, whose powerful chiaroscuro effects enhanced the psychological intensity of his paintings.

Stylistic characteristics of both pictorial traditions—the Utrecht school and that of Rembrandt—are found in Vermeer's early large-scale biblical and mythological paintings, such as Diana and Her Companions (1655–56) and Christ in the House of Mary and Martha ( 1655). The most striking assimilation of the two traditions is apparent in Vermeer's The Procuress (1656). The subject of this scene of mercenary love is derived from a painting by the Utrecht-school artist Dirck van Baburen in the collection of Vermeer's mother-in-law, while the deep reds and yellows and the strong chiaroscuro effects are reminiscent of Rembrandt's style of painting. The dimly lit figure at the left of the composition is probably a self-portrait in which Vermeer assumes the guise of the Prodigal Son, a role that Rembrandt had also played in one of his own “merry company” scenes.

In the early 1650s Vermeer might also have found much inspiration back within his native Delft, where art was undergoing a rapid transformation. The most important artist in Delft at the time was Leonard Bramer, who produced not only small-scale history paintings—that is, morally edifying depictions of biblical or mythological subjects—but also large murals for the court of the Prince of Orange. Documents indicate that Bramer, who was Catholic, served as a witness for Vermeer at his marriage. Although it would appear that Bramer was, at the very least, an early advocate for the young artist, nowhere is it stated that he was Vermeer's teacher.

Another important painter who Vermeer must have known in Delft during this period was Carel Fabritius, a former Rembrandt pupil. Fabritius's evocatively pensive images and innovative use of perspective seem to have profoundly influenced Vermeer. This connection was noted by the poet Arnold Bon, who, in writing about Fabritius's tragic death in 1654 in the Delft powder-house explosion, noted that “Vermeer masterfully trod in [Fabritius's] path.” However, while Vermeer was aware of Fabritius's work, there is also no evidence to suggest that he studied with Fabritius.

Whatever the circumstances of his early artistic education, by the second half of the 1650s Vermeer began to depict scenes of daily life. These “genre” paintings are those with which he is most often associated. Gerard Terborch, an artist from Deventer who masterfully rendered texture in his depictions of domestic activities, may well have encouraged Vermeer to pursue scenes of everyday life. Certainly Terborch's influence is apparent in one of Vermeer's earliest genre paintings, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window ( 1657), in which he created a quiet space for the young woman to read her letter. Unlike the characteristically dark interiors of Terborch, however, Vermeer bathed this remarkably private scene in a radiant light that streams in from an open window. The painting also reveals Vermeer's developing interest in illusionism, not only in the inclusion of a yellowish green curtain hanging from a rod stretching across the top of the painting, but also in the subtle reflections of the woman's face in the open window.

Hooch was a master of using perspective to create a light-filled interior or courtyard scene in which figures are comfortably situated. Although no documents link Vermeer and de Hooch, it is highly probable that the two artists were in close contact during this period, since the subject matter and style of their paintings during those years were quite similar. Vermeer's The Little Street ( 1657–58) is one such work: as with de Hooch's courtyard scenes, Vermeer has here portrayed a world of domestic tranquillity, where women and children go about their daily lives within the reassuring setting of their homes.

Maturity

Beginning in the late 1650s and lasting over the course of about one decade—a remarkably brief period of productivity, given the enormity of his reputation—Vermeer would create many of his greatest paintings, most of them interior scenes. No other contemporary Dutch artist created scenes with such luminosity or purity of colour, and no other painter's work was infused with a comparable sense of timelessness and human dignity.

As he reached the height of his abilities, Vermeer became renowned within his native city of Delft and was named the head of the painters' guild in 1662. Although no commissions for Vermeer's paintings are known, it does appear that during this and other periods he sold his work primarily to a small group of patrons in Delft. For example, over two decades after Vermeer's death, no fewer than 21 of his paintings were sold from the estate of Jacob Dissius, a Delft collector.

Themes

During the height of his career, in paintings depicting women reading or writing letters, playing musical instruments, or adorning themselves with jewelry, Vermeer sought ways to express a sense of inner harmony within everyday life, primarily in the confines of a private chamber. In paintings such as Young Woman with a Water Pitcher ( 1664–65), Woman with a Pearl Necklace ( 1664), and Woman in Blue Reading a Letter ( 1663–64), he utilized the laws of perspective and the placement of individual objects—chairs, tables, walls, maps, window frames—to create a sense of nature's underlying order. Vermeer's carefully chosen objects are never placed randomly; their positions, proportions, colours, and textures work in concert with his figures. Radiant light plays across these images, further binding the elements together.

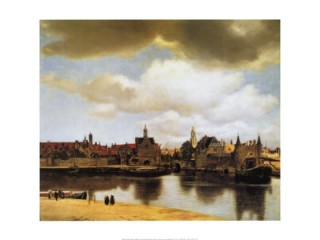

The emotional power of Vermeer's magnificent View of Delft ( 1660–61) similarly results from his ability to transform an image of the physical world into a harmonious, timeless visual expression. In this masterpiece Vermeer depicted Delft from across its harbour, where transport boats would unload after navigating inland waterways. Beyond the shadowed frieze of Delft's venerable protective walls and massive gates, bright sunshine illuminates the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk, burial place of the princes of Orange and the city's symbolic core. Aside from the use of light, the painting's forcefulness also stems from its large scale and tangible illusion of reality. The buildings take on a physical presence because of Vermeer's suggestive manner of juxtaposing small dots of unmodulated colours with touches of the brush; he used a similar technique to suggest the reflection of water on the sides of the boats.

Although he drew his inspiration from his observations of everyday life in such mature work, Vermeer remained at his core a history painter, seeking to evoke abstract moral and philosophical ideas. This quality is particularly evident in Woman Holding a Balance ( 1664). In this remarkable image, a woman stands serenely before a table that bears a jewelry box draped with strands of gold and pearls while she waits for her small handheld balance to come to rest. Although the subdued light entering the room and the refined textures of the jewelry and fur-trimmed jacket are realistically rendered, the painting of the Last Judgment hanging on the rear wall signifies that the artist conceived the scene allegorically. As the woman stands by the jewelry box and Judgment scene, her calm expression indicates a realization: she must maintain balance in her own life by not allowing transient worldly treasures to outweigh lasting spiritual concerns.

Surprisingly little is known of Vermeer's attitude toward his role as an artist. The philosophical framework for his approach to his craft can perhaps be surmised, however, from another work of this period, The Art of Painting ( 1665–66). With a large curtain, drawn back as though revealing a tableau vivant, Vermeer announced his allegorical intent for this large and imposing work. The scene depicts an elegantly dressed artist in the midst of portraying the allegorical figure of Clio, the muse of history, who is recognizable through her attributes: a laurel wreath symbolizing honour and glory, the trumpet of fame, and a large book signifying history. Vermeer juxtaposed Clio and a large wall map of the Netherlands to indicate that the artist, through his awareness of history and his ability to paint elevated subjects, brings fame to his native city and country. This painting was so important to Vermeer that his widow tried to keep it from creditors even when the family was destitute.

Working methods

Perhaps the most recognizable feature of Vermeer's greatest paintings is their luminosity. Technical examinations have demonstrated that Vermeer generally applied a gray or ochre ground layer over his canvas or panel support to establish the colour harmonies of his composition. He was keenly aware of the optical effects of colour, and he created translucent effects by applying thin glazes over these ground layers or over the opaque paint layers defining his forms. His works further seem to be permeated with a sense of light as a result of his use of small dots of unmodulated colour—as in the aforementioned buildings and water of View of Delft, and in foreground objects in other works, such as the crusty bread in The Milkmaid (1658–60) and the finials of the chair in Girl with the Red Hat (1665–66).

The diffuse highlights Vermeer achieved are comparable to those seen in a camera obscura, a fascinating optical device that operates much like a box camera. The 17th-century camera obscura created an image by allowing light rays to enter a box through a small opening that was sometimes fitted with a focusing tube and lens. Owing to the device's limited depth of field, the image it projected would have many unfocused areas surrounded by hazy highlights. Vermeer was apparently fascinated by these optical effects, and he exploited them to give his paintings a greater sense of immediacy.

Some have argued that Vermeer used the device to plan his compositions and even that he traced the images projected onto the ground glass at the back of the camera obscura. However, such a working process is most unlikely. Vermeer instead relied primarily on traditional perspective constructions to create his sense of space. It has been discovered, for example, that small pinholes exist in many of his interior genre scenes at the vanishing point of his perspective system. Strings attached to the pin would have guided him in constructing the orthogonal lines that would have defined the recession of floors, windows, and walls. Vermeer carefully placed this vanishing point to emphasize the main compositional element in the painting. In Woman Holding a Balance, for example, it occurs at the fingertip of the hand holding the balance, thus enhancing his overall philosophical message. Such attention to detail helps explain the small size of Vermeer's creative output, even during his most fertile period. He must have worked slowly, carefully thinking through the character of his composition and the manner in which he wanted to execute it.

Later life and work

In 1670 Vermeer was again elected head of the Delft painting guild. Vermeer's late style is crisper in character, with greater atmospheric clarity than that found in his paintings of the 1660s. The carefully modulated tones and colours he used in those earlier works gave way to a more direct, even bolder technique about 1670. For example, he used sharply defined planes of colour and angular rhythms to convey a sense of emotional energy in such paintings as Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid (1670) and The Guitar Player (1670).

The artist's fortunes deteriorated drastically toward the end of his life, mainly owing to the disastrous economic climate in Holland following its invasion by French troops in 1672. When Vermeer died in 1675, he left behind a wife, 11 children, and enormous debts.

Assessment

Vermeer's fame was not widespread during his lifetime, largely because his paintings were collected by local patrons and because his creative output was small. After his death the paintings continued to be admired by a small group of connoisseurs, primarily in Delft and Amsterdam.

By the 19th century a number of Vermeer's paintings had been attributed to other, more prolific Dutch artists, among them de Hooch. However, when the French painter-critic Théophile Thoré (who wrote under the pseudonym W. Bürger) published his enthusiastic descriptions of Vermeer's paintings in 1866, passion for the artist's work reached a broader public. As private collectors and public museums actively sought to acquire his rare paintings during the early years of the 20th century, prices for his work skyrocketed. This situation encouraged the production of forgeries, the most notorious of which were those painted by Han van Meegeren in the 1930s. At the end of the 20th century Vermeer's fame continued to rise, fueled in part by an exhibition of his work held in 1995–96 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and at the Mauritshuis in The Hague.

The remarkably small oeuvre of the artist has thus only increased in popularity across generations. Vermeer found beneath the accidents of nature a realm infused with harmony and order, and, in giving visual form to that realm, he revealed the poetry existing within transient moments of human existence. He rarely explained the exact meanings of his paintings, preferring instead to allow each viewer to contemplate their significance. As a result, his masterpieces continue to engage fully each contemporary observer, much as they must have engaged their viewers in 17th-century Delft.