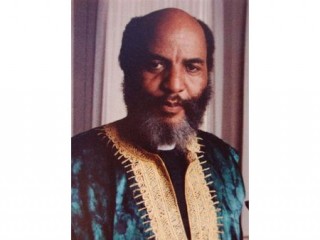

James L. Bevel biography

Date of birth : 1936-10-19

Date of death : 2008-12-19

Birthplace : Ittabena, Mississippi, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2011-07-19

Credited as : Minister, leader of Civil Rights Movement , Martin Luther King

James Luther Bevel was born in the farming community of Ittabena, Mississippi, on October 19, 1936. This civil rights activist, minister, lyricist, and human rights advocate gained a national reputation for both his impassioned activism and managerial efficiency as one of Martin Luther King's top lieutenants in the freedom struggles of the 1960s. Bevel served briefly in the United States Naval Reserve from 1954 to 1955. He received a B.A. degree from the American Baptist Theology Seminary in 1961. He married another civil rights activist, Diane Judith Nash, and had two children: Sherrillyn Jill and Douglas John Bevel. Ordained in the Baptist ministry in 1959, Bevel pastored a church in Dixon, Tennessee, from 1959 to 1961.

James Bevel was philosophically committed to the notion that religion was part of the larger human rights struggle and that the church should serve as an institution of social change. He was chairman of the Nashville Student Movement from 1960 to 1961. In that same year, he was one of the founding members of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and held the position of Mississippi field secretary. Interested not only in preaching "the good word," but also dedicated to its permanence, he helped to create the Mississippi Free Press in 1960 to publish various religious and social-action pamphlets. In addition, he headed the civil action programs of the Albany Movement in Georgia to fight racism and discrimination.

As one of several young activists working with Martin Luther King, Jr., Bevel was made head of direct action and became a youth training specialist in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which he joined in 1961. Within SCLC his organizational skills and "we-can-do-it" spirit allowed him to evolve into one of its most prominent young leaders. In 1963 he was asked to go to Birmingham, Alabama, as chief organizer of the Birmingham Movement of the SCLC, and in 1965 he became its project director.

Bevel, always involved in several groups at once, helped to sponsor the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) from 1962 to 1964. This group created a statewide coalition of civil rights groups, including SCLC, SNCC, and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). This cooperative effort was unique in its attempts to help the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in registering Blacks to vote and making them politically active and socially aware.

In 1965, when the world turned its attention to the violent response of Birmingham, Alabama, to peaceful Black protest, James L. Bevel was there directing the campaign which eventually led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which opened up the political process to Blacks throughout the South. Always distinctive in his informal denim clothing,

shaved head, and skull-cap, Bevel went to Chicago in 1966 as King's advance man for SCLC's ill-fated national opening of the housing campaign. In Chicago Bevel was program director of the Westside Christian Parish, where he had extensive dealings with gangs, recalcitrant political leaders, and a rapidly growing antagonism between older, more moderate Black leaders on one hand and young militants on the other. Bevel, who probably conducted as many nonviolence seminars as any single activist, used his skills in demanding that the Blackstone Rangers (a local gang) eschew violence as an avenue toward social change. He even went so far as to show a film on the 1965 Watts Riot in an attempt to forestall violent confrontations with Chicago's police during demonstrations. Though respected and somewhat revered, the young people of Chicago were not as receptive to Bevel's message as his southern audiences.

A man of many talents, James L. Bevel was also noted for his lyrical abilities. As a composer of freedom songs, Bevel's most popular works were: "Dod-Dog" (1959), "Why Was a Darky Born" (1961), and "I Know We'll Meet Again" (1969). This last song is a sentimental testament to Bevel's leader, friend, and mentor, the late Martin Luther King, Jr. With King when he was shot in 1968, Bevel saw his leader gunned down. James Earl Ray was the man arrested, indicted, and convicted of King's murder. Bevel believed that Ray was innocent. He even went to the jail-house and told him so, even though Ray rejected his help and refused to let him into his cell. Bevel told Ray that King was assassinated by capitalists threatened by King's mobilization of the poor or by the military-industrial complex which was aghast at King's denunciation of the Vietnam War and his perceived left wing shift.

Bevel's views on Ray and a possible conspiracy created consternation among his friends and many of King's followers. Yet it was Bevel who convinced King of the connection between the denial of civil rights in America and the war in Vietnam, as well as the plight of the poor world-wide. Bevel actually jarred King's thinking when he left his position as program director at SCLC to become executive director of the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam in early 1967. Spring sought to create a national anti-war crusade and, after King had denounced the war, was eventually successful in having him address an anti-war rally that Bevel organized in New York.

Bevel was certainly one of the most influential, though least known, civil rights activists. Martin Luther King, Jr., would not have achieved many of his successes had it not been for men and women like James and Diane Bevel. As one of King's most effective front-men and as a dedicated worker who believed in direct-action, Bevel was a dynamic symbol of the new generation of leaders which included Andrew Young, Jesse Jackson, C.T. Vivian, Hosea Williams, and many others of both local and national prominence. Although not as well-known as some of these, Bevel's civil rights record did not go unnoticed. In 1963 he received the Peace Award from the War Resisters League and in 1965 was awarded the prestigious Rosa Parks Award by the SCLC.

Following King's death, Bevel left the SCLC after unsuccessful efforts to refocus the organization's priorities on education, international arms reduction, and a retrial of King's accused assassin. He wrote and spoke extensively on nonviolent theology, continued to believe in Ray's innocence, and founded Students for Education and Economic Development (SEED).

By 1980 Bevel's political leanings had shifted to the right and he campaigned for Ronald Reagan. Four years later he ran unsuccessfully as a Republican for the House of Representatives from Chicago and, in 1992, was the vice-presidential candidate on the Lyndon LaRouche ticket. Bevel's association with Louis Farrahkan led in 1995 to his participation in the National Day of Atonement/Million Man March movement which encouraged African American males to rededicate themselves as husbands, sons, and fathers.