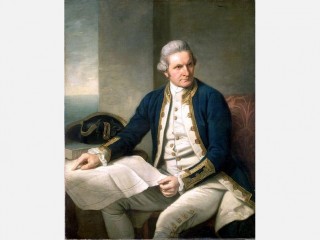

James Cook biography

Date of birth : 1728-11-07

Date of death : 1779-02-14

Birthplace : Marton, Yorkshire, Great Britain

Nationality : British

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-04-29

Credited as : Explorer and navigator, Royal Navy, HM Bark Endeavour

15 votes so far

Cook joined the British merchant navy as a teenager and joined the Royal Navy in 1755. He saw action in the Seven Years' War, and subsequently surveyed and mapped much of the entrance to the Saint Lawrence River during the siege of Quebec. This allowed General Wolfe to make his famous stealth attack on the Plains of Abraham, and helped to bring Cook to the attention of the Admiralty and Royal Society. This notice came at a crucial moment both in his personal career and in the direction of British overseas exploration, and led to his commission in 1766 as commander of HM Bark Endeavour for the first of three Pacific voyages.

First voyage (1768–71)

In 1766, the Royal Society hired Cook to travel to the Pacific Ocean to observe and record the transit of Venus across the Sun. Cook was promoted to Lieutenant and named as commander of the expedition. The expedition sailed from England in 1768, rounded Cape Horn and continued westward across the Pacific to arrive at Tahiti on 13 April 1769, where the observations were to be made. However, the result of the observations was not as conclusive or accurate as had been hoped. Cook later mapped the complete New Zealand coastline, making only some minor errors. He then sailed west, reaching the south-eastern coast of the Australian continent on 19 April 1770, and in doing so his expedition became the first recorded Europeans to have encountered its eastern coastline.

On 23 April he made his first recorded direct observation of indigenous Australians at Brush Island near Bawley Point, noting in his journal: "...and were so near the Shore as to distinguish several people upon the Sea beach they appear'd to be of a very dark or black Colour but whether this was the real colour of their skins or the C[l]othes they might have on I know not". On 29 April Cook and crew made their first landfall on the mainland of the continent at a place now known as the Kurnell Peninsula, which he named Botany Bay after the unique specimens retrieved by the botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander. It is here that James Cook made first contact with an Aboriginal tribe known as the Gweagal.

After his departure from Botany Bay he continued northwards, and a mishap occurred when Endeavour ran aground on a shoal of the Great Barrier Reef, on 11 June, and "nursed into a river mouth on 18 June 1770". The ship was badly damaged and his voyage was delayed almost seven weeks while repairs were carried out on the beach (near the docks of modern Cooktown, at the mouth of the Endeavour River). Once repairs were complete the voyage continued, sailing through Torres Strait and on 22 August he landed on Possession Island, where he claimed the entire coastline he had just explored as British territory. He returned to England via Batavia (modern Jakarta, Indonesia), the Cape of Good Hope and the island of Saint Helena, arriving on 12 July 1771.

Cook's journals were published upon his return, and he became something of a hero among the scientific community. Among the general public, however, the aristocratic botanist Joseph Banks was a bigger hero. Banks even attempted to take command of Cook's second voyage, but removed himself from the voyage before it began, and Johann Reinhold Forster and his son Georg Forster were taken on as scientists for the voyage. Cook's son George was born five days before he left for his second voyage.

Second voyage (1772–75)

Shortly after his return, Cook was promoted to the rank of Commander. Then once again he was commissioned by the Royal Society to search for the mythical Terra Australis. On his first voyage, Cook had demonstrated by circumnavigating New Zealand that it was not attached to a larger landmass to the south; and although by charting almost the entire eastern coastline of Australia he had shown it to be continental in size, the Terra Australis being sought was supposed to lie further to the south. Despite this evidence to the contrary, Dalrymple and others of the Royal Society still believed that this massive southern continent should exist.

Cook commanded HMS Resolution on this voyage, while Tobias Furneaux commanded its companion ship, HMS Adventure. Cook's expedition circumnavigated the globe at a very high southern latitude, becoming one of the first to cross the Antarctic Circle on 17 January 1773. He also surveyed, mapped and took possession for Britain of South Georgia explored by Anthony de la Roché in 1675, discovered and named Clerke Rocks and the South Sandwich Islands ("Sandwich Land"). In the Antarctic fog, Resolution and Adventure became separated. Furneaux made his way to New Zealand, where he lost some of his men following an encounter with Māori, and eventually sailed back to Britain, while Cook continued to explore the Antarctic, reaching 71°10'S on 31 January 1774.

Third voyage (1776–79) and death

A statue of James Cook stands in Waimea, Kauai commemorating his first contact with the Hawaiian Islands at the town's harbour on January 1778

On his last voyage, Cook once again commanded HMS Resolution, while Captain Charles Clerke commanded HMS Discovery. Ostensibly the voyage was planned to return Omai to Tahiti; this is what the general public believed, as he had become a favourite curiosity in London. Principally the purpose of the voyage was an attempt to discover the famed Northwest Passage. After returning Omai, Cook travelled north and in 1778 became the first European to visit the Hawaiian Islands. In passing and after initial landfall in January 1778 at Waimea harbour, Kauai, Cook named the archipelago the "Sandwich Islands" after the fourth Earl of Sandwich, the acting First Lord of the Admiralty.

From the South Pacific, he went northeast to explore the west coast of North America north of the Spanish settlements in Alta California. He made landfall at approximately 44°30′ north latitude, near Cape Foulweather on the Oregon coast, which he named. Bad weather forced his ships south to about 43° north before they could begin their exploration of the coast northward. He unknowingly sailed past the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and soon after entered Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island. He anchored near the First Nations village of Yuquot. Cook's two ships spent about a month in Nootka Sound, from March 29 to April 26, 1778, in what Cook called Ship Cove, now Resolution Cove, at the south end of Bligh Island, about 5 miles (8.0 km) east across Nootka Sound from Yuquot, a Nuu-chah-nulth village whose chief who Cook did not identify but may have been Maquinna. Relations between Cook's crew of the people of Yuquot were cordial if sometimes strained. In trading, the people of Yuquot demanded much more valuable items than the usual trinkets that had worked for Cook's crew in Hawaii. Metal objects were much desired, but the lead, pewter, and tin traded at first soon fell into disrepute. The most valuable items the British received in trade were sea otter pelts. Over the month long stay the Yuquot "hosts" essentially controlled the trade with the British vessels, instead of vice versa. Generally the natives visited the British vessels at Resolution Cove instead of the British visiting the village of Yuquot at Friendly Cove.

After leaving Nootka Sound, Cook explored and mapped the coast all the way to the Bering Strait, on the way identifying what came to be known as Cook Inlet in Alaska. It has been said that, in a single visit, Cook charted the majority of the North American northwest coastline on world maps for the first time, determined the extent of Alaska and closed the gaps in Russian (from the West) and Spanish (from the South) exploratory probes of the Northern limits of the Pacific.

The Bering Strait proved to be impassable, although he made several attempts to sail through it. He became increasingly frustrated on this voyage, and perhaps began to suffer from a stomach ailment; it has been speculated that this led to irrational behaviour towards his crew, such as forcing them to eat walrus meat, which they found inedible.

Cook returned to Hawaiʻi in 1779. After sailing around the archipelago for some eight weeks, he made landfall at Kealakekua Bay, on 'Hawaiʻi Island', largest island in the Hawaiian Archipelago. Cook's arrival coincided with the Makahiki, a Hawaiian harvest festival of worship for the Polynesian god Lono. Indeed the form of Cook's ship, HMS Resolution, or more particularly the mast formation, sails and rigging, resembled certain significant artifacts that formed part of the season of worship. Similarly, Cook's clockwise route around the island of Hawai'i before making landfall resembled the processions that took place in a clockwise direction around the island during the Lono festivals. It has been argued (most extensively by Marshall Sahlins) that such coincidences were the reasons for Cook's (and to a limited extent, his crew's) initial deification by some Hawaiians who treated Cook as an incarnation of Lono. Though this view was first suggested by members of Cook's expedition, the idea that any Hawaiians understood Cook to be Lono, and the evidence presented in support of it was challenged in 1992.

After a month's stay, Cook got under sail again to resume his exploration of the Northern Pacific. However, shortly after leaving Hawaiʻi Island, the foremast of the Resolution broke and the ships returned to Kealakekua Bay for repairs. It has been hypothesised that the return to the islands by Cook's expedition was not just unexpected by the Hawaiians, but also unwelcome because the season of Lono had recently ended (presuming that they associated Cook with Lono and Makahiki). In any case, tensions rose and a number of quarrels broke out between the Europeans and Hawaiians. On 14 February at Kealakekua Bay, some Hawaiians took one of Cook's small boats. Normally, as thefts were quite common in Tahiti and the other islands, Cook would have taken hostages until the stolen articles were returned. Indeed, he attempted to take hostage the King of Hawaiʻi, Kalaniʻōpuʻu. The Hawaiians prevented this, and Cook's men had to retreat to the beach. As Cook turned his back to help launch the boats, he was struck on the head by the villagers and then stabbed to death as he fell on his face in the surf.The Hawaiians dragged his body away. Four of the Marines with Cook were also killed and two wounded in the confrontation.

Some scholars suggest that Cook's return to Hawaiʻi outside the season of worship for Lono, which was synonymous with "peace", and thus in the season of "war" (being dedicated to Kū, god of war) may have upset the equilibrium and fostered an atmosphere of resentment and aggression from the local population. Coupled with a jaded grasp of native diplomacy and a burgeoning but limited understanding of local politics, Cook may have inadvertently contributed to the tensions that ultimately brought about his demise.

The esteem in which he was nevertheless held by the Hawaiians resulted in his body being retained by their chiefs and elders. Following the practice of the time, Cook's body underwent funerary rituals similar to those reserved for the chiefs and highest elders of the society. The body was disembowelled, baked to facilitate removal of the flesh, and the bones were carefully cleaned for preservation as religious icons in a fashion somewhat reminiscent of the treatment of European saints in the Middle Ages. Some of Cook's remains, disclosing some corroborating evidence to this effect, were eventually returned to the British for a formal burial at sea following an appeal by the crew.

Clerke took over the expedition and made a final attempt to pass through the Bering Strait. Following the death of Clerke, Resolution and Discovery returned home in October 1780 commanded by John Gore, a veteran of Cook's first voyage, and Captain James King. Cook's account of his third and final voyage was completed upon their return by King.

Cook almost encountered the mainland of Antarctica, but turned back north towards Tahiti to resupply his ship. He then resumed his southward course in a second fruitless attempt to find the supposed continent. On this leg of the voyage he brought with him a young Tahitian named Omai, who proved to be somewhat less knowledgeable about the Pacific than Tupaia had been on the first voyage. On his return voyage, in 1774 he landed at the Friendly Islands, Easter Island, Norfolk Island, New Caledonia, and Vanuatu. His reports upon his return home put to rest the popular myth of Terra Australis.

Another accomplishment of the second voyage was the successful employment of the Larcum Kendall K1 chronometer, which enabled Cook to calculate his longitudinal position with much greater accuracy. Cook's log was full of praise for the watch and the charts of the southern Pacific Ocean he made with its use were remarkably accurate – so much so that copies of them were still in use in the mid 20th century.

Upon his return, Cook was promoted to the rank of Captain and given an honorary retirement from the Royal Navy, as an officer in the Greenwich Hospital. His acceptance was reluctant, insisting that he be allowed to quit the post if the opportunity for active duty presented itself. His fame now extended beyond the Admiralty and he was also made a Fellow of the Royal Society and awarded the Copley Gold Medal, painted by Nathaniel Dance-Holland, dined with James Boswell and described in the House of Lords as "the first navigator in Europe". But he could not be kept away from the sea. A third voyage was planned to find the Northwest Passage. Cook travelled to the Pacific and hoped to travel east to the Atlantic, while a simultaneous voyage travelled the opposite way.

Cook charted many areas and recorded several islands and coastlines on European maps for the first time. His achievements can be attributed to a combination of seamanship, superior surveying and cartographic skills, courage in exploring dangerous locations to confirm the facts (for example dipping into the Antarctic circle repeatedly and exploring around the Great Barrier Reef), an ability to lead men in adverse conditions, and boldness both with regard to the extent of his explorations and his willingness to exceed the instructions given to him by the Admiralty.

Cook died in Hawaii in a fight with Hawaiians during his third exploratory voyage in the Pacific in 1779.