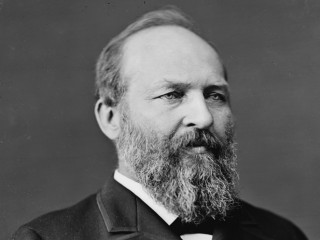

James A. Garfield biography

Date of birth : 1831-11-19

Date of death : 1881-09-19

Birthplace : Cleveland, Ohio, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-07-15

Credited as : Politician, former President of United States,

James A. Garfield was born in the log cabin of American myth on Nov. 19, 1831, near Cleveland, Ohio. Although his family dated back to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, his immediate ancestors had not prospered, and Garfield's upbringing was plagued by dire poverty. His father died when James was 2 years old, and he was early put out to labor to help keep the family intact.

Garfield matriculated at the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute, later called Hiram College. He graduated from Williams College and, before he was 30, became a lay preacher for the Disciples of Christ. He taught school briefly and returned to Hiram as a professor and head of the college, but he did not enjoy the life. "You and I know," he wrote a friend, "that teaching is not the work in which a man can live and grow." Still, Garfield remained bookish throughout his life, and while by no means brilliant or original, he emerges as truly distinctive in his occasional writings, letters, and diary. These reveal a perspicacious mind, shrewd insight into his contemporaries' personalities, and a rare comprehension among politicos of the day of the vast changes through which the United States was going.

In 1859 Garfield was elected to the Ohio Senate and became a leading Union supporter in the Civil War. He accepted a commission as colonel and, typically, set about studying military strategy and organization. His readings must have been well selected because his rise in rank was rapid even for the Civil War era. An active role in the Battle of Middle Creek on Jan. 10, 1862, made him a brigadier general, and, in April, he fought during the bloody second day at Shiloh. After that he left the lines to become chief of staff through the Chickamauga campaign, organizing a division of military information and being promoted to major general.

Garfield's military career reflected the dexterity with which he would later escape political crises unscathed, for although he was closely associated with several disasters that ruined associates, he himself escaped blame. Indeed, in December 1863 Garfield was elected to the House of Representatives in recognition of his military service and, until his death, was never again out of Federal office. His Ohio district was safe for Republicans, so Garfield could concentrate on the affairs of office, and he was the leader of his party in the House during the presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes.

Garfield was capable of neatly straddling a volatile issue. He was never so strong on the high-tariff issue as were most of his Republican colleagues and, as late as his presidential campaign of 1880, he remained publicly equivocal on the issue of Federal patronage. The Federal jobs at the disposal of the party in power were the life-blood of politics during the "gilded age." One wing of the Republican party—the "stalwarts"—called for no dalliance on the question, claiming the jobs as the just due of those who worked to put the party in power. Another wing of reformers, the "doctrinaires," felt that the quality of government would be improved if Federal jobs were assigned on the basis of merit. Garfield attempted to placate both sides.

On the money question Garfield was firm, standing unalterably for "hard" currency when many of his former constituents called for inflation. But he was less steadfast on the Southern question, alternating between "waving the bloody shirt"—exploiting Northern bitterness toward the South over the war—and supporting a more compromising attitude.

Scandal nearly wrecked Garfield's career when he was accused of accepting money in return for supporting a congressional subsidy of the transcontinental railroad's construction company. But he managed to sidestep and survive the accusation, and he also weathered the revelation that he had accepted a legal fee from a company involved in government-contracted improvement of Washington streets. These lapses in ethics were more the result of carelessness than personal corruption, and Garfield in his last years was extremely careful to avoid any possible conflicts of interest. On the whole, he had a good record in the graft-sullied political world of the day, and reformers who could not support James G. Blaine were willing to accept Garfield.

In 1880 Garfield was elected to the U.S. Senate from Ohio, but before he took his seat, he agreed to manage John Sherman's campaign to win the Republican presidential nomination. The chief Republican candidates that year were former U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant and Senator James G. Blaine. Sherman's hopes were based on an anticipated deadlock between the two front-runners, which would force the convention to turn to him as a compromise candidate. The convention did, indeed, deadlock and settle on a third person, but that person was Garfield rather than Sherman. Toward the end of his life Sherman became convinced that his manager had actively betrayed him, but close examination of the records by several historians indicates that this was not so. Garfield knew before the convention that certain parties were working for him as a compromise candidate, but he neither encouraged nor effectively discouraged the talk. He certainly had presidential ambitions, but like a good party regular, he recognized Sherman's seniority among Ohio politicians and was willing to wait his turn. When the opportunity beckoned in 1880, he was more than ready.

The immediate problem was the party's "stalwarts." Garfield had selected one of their number, Chester A. Arthur, as his vice-presidential candidate, but the leader of the "stalwarts," New York politician Roscoe Conkling, refused to work to get the important New York vote without specific promises from Garfield on patronage. Conkling believed that he received such promises and did help elect Garfield, but soon after the election, the two fell out. Garfield named Conkling's archenemy, James G. Blaine, to be his secretary of state and increasingly relied on Blaine's counsel. In a battle over the appointment of the collector of customs for the Port of New York (one of the richest plums in the Federal patronage), Conkling resigned his Senate seat and asked the New York Legislature, in effect, to rebuke the President by reelecting him. What might have happened under normal circumstances is impossible to tell, for on July 2, 1881, Garfield was shot in the back in a Washington railroad station by a deranged man named Charles Guiteau, who claimed he had killed the President in order to put Chester A. Arthur into office.

Garfield did not die immediately. But doctors could not locate one of the bullets, and infection eventually sapped his strength. Conkling was not reelected in the shocked aftermath of the shooting, and a civil service reform bill aimed at Conkling-style politics eventually passed Congress. But Garfield never left his bed; he died at Alberon, N.J., on Sept. 19, 1881.