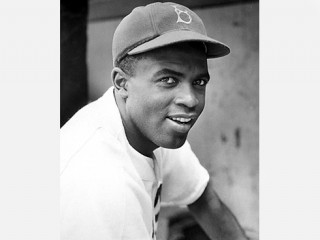

Jackie Robinson (Brooklyn Dodgers) biography

Date of birth : 1919-01-19

Date of death : 1972-11-24

Birthplace : Cairo, Georgia, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2022-02-17

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, Jackie Robinson Brooklyn dodgers,

60 votes so far

Baseball's Great Integrator.

Jackie Robinson may have had more influence on the integration of sports than any other athlete in history. When he began playing with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, he broke the color line in professional baseball and paved the way for the entry of black players into all professional sports. Monte Irvin, a black baseball player who came into the major leagues soon after Robinson, was quoted in The New York Times Book of Sports Legends as saying, "Jackie Robinson opened the door of baseball to all men. He was the first to get the opportunity, but if he had not done such a great job, the path would have been so much more difficult."

Excels in Athletics.

The grandson of a slave, Jack Roosevelt Robinson was the youngest of five children and spent his early years in Georgia. After his father deserted the family when Jackie was six months old, his mother, Mallie Robinson, moved the family to California in search of work. California also subjected blacks to segregation at that time, but to a lesser degree than in the deep South. The young Jackie defused his anger over this prejudice by immersing himself in sports. He displayed extraordinary athletic skills in high school, excelling at football, basketball, baseball, and track. After helping Pasadena Junior College win the Junior College Football Championship, Robinson took his athletic prowess to the University of California at Los Angeles and became a top collegiate running back in 1939.

Drafted into Army.

Robinson left college before graduating, having used up his athletic eligibility. Then he held a job with the National Youth Administration work camp until the camp was closed due to the onset of World War II. In the fall of 1941 he joined the Honolulu Bears professional football team, then was drafted onto a new "team" in 1942--the U.S. Army. While stationed at Fort Riley in Kansas with heavyweight champion Joe Louis, Robinson worked with Louis to eradicate unfair treatment of blacks in the military, but inequities would persist in the armed forces for decades to come. Robinson was discharged from the army in 1945 because his ankles had been weakened playing football.

Joins Negro League.

Robinson joined the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro League in 1945 for a reported $400 a month. Although he soon became one of the league's top players, he was not fond of the low pay and relentless traveling and apparently had no intention of making baseball a career. That attitude was changed due to the efforts of Brooklyn Dodger president Branch Rickey. Starting in 1943, Rickey had been searching for a black player to bring into the major leagues, which were closed to blacks at the time. Dodger owner Walter O'Malley stated in Harvey Frommer's book Rickey and Robinson: "Branch wanted Jackie because he knew Jackie had absolutely fierce pride and determination."

Signs with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

On 23 October 1945, Robinson signed a contract with Rickey to play for one of the Dodgers' farm teams, the Montreal Royals in the International League. Many owners and sportswriters were against this integration, claiming that it would destroy major league baseball, but both Rickey and Robinson were confident of the move. According to Frommer, Robinson said, "I think I am the right man to pick for this test. There is no possible chance that I will flunk it or quit before the end for any other reason than that I am not a good enough ballplayer."

The Promise.

Spring training in Florida was rough for Robinson due to segregation laws. He was forced to ride in the back of buses, and some games in which he was scheduled to play were canceled due to his presence. Nevertheless, he proved his worth that season by leading the Royals to the championship in the Little World Series. His performance made it clear that he was ready for the major leagues, but not all of the Dodgers were supportive of moving Robinson up to the big time. Some players on the team circulated a petition saying that they wouldn't play with Robinson, but hardly anyone signed it. When Rickey brought Robinson up to the Dodgers, he made the player promise to rein in his temper when he was subjected to racial taunts on the playing field, at least for the first year. Robinson reluctantly agreed, but once a star he allowed his pride to resurface during disputes that were racially tinged.

Skills Flourish Despite Racial Abuse.

Robinson's arrival on the major-league scene in 1947 prompted a slew of racially motivated actions. The St. Louis Cardinals threatened to go on strike, then backed down when National League president Ford Frick threatened to ban all strikers from professional baseball. Pitchers often threw the ball directly at Robinson, base runners tried to spike him, and he was subjected to a steady stream of racial insults. He received hate mail, death threats, and even warnings that his baby boy would be kidnapped. Through it all, though, Robinson held his tongue in deference to Rickey's wishes. As the much-maligned player stated in his autobiography I Never Had It Made, "I never cared about acceptance as much as I cared about respect."

Wins Rookie of the Year Honors.

Robinson let his playing do the talking, and before long he was known as one of the most exciting players in baseball. Soon fans both black and white were filling ballparks to see him in action, and the Dodgers set new attendance records. Most of his fellow teammates fully supported him as they became convinced of Robinson's value to the club. Despite the adversity he faced, Robinson led the league in stolen bases and was named Rookie of the Year.

Heroics Open Baseball's Door.

By the end of the following season, Robinson was no longer willing to hold his temper in check. He would often get into shouting matches with opponents, as well as umpires. His playing kept improving, reaching a peak in 1949 when his exploits earned him a batting title and the Most Valuable Player award. By this time Robinson was famous throughout the world. He had a string of six consecutive seasons batting over .300 and became renowned for his daring steals of home. His success had opened the door to a string of other great black players such as Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, and Junior Gilliam. In 1950 Robinson was paid an annual salary of $35,000, tops in Dodger history, and a movie about his life opened in theaters.

Active Supporter of Black Causes.

As his fame grew, Robinson became more fervent in his protests against racist attitudes, and he offered more support for civil rights causes. His status on the team, however, changed in the 1951 season due to Rickey being replaced as president of the Dodgers by Walter O'Malley. A tremendous admirer of Rickey, Robinson was greatly disappointed by the changing of the guard, especially since O'Malley was less tolerant than Rickey of his speaking out on racial issues. Nevertheless, Robinson continued offering support for black causes and advice to black players in particular, including those on opposing teams.

Retirement.

Robinson's glory years as a player were coming to an end by the mid-1950s. He had developed a bad relationship with manager Walter Alston, and his average fell to .256 in 1955 during an injury-plagued season. After being sold in December of 1956 to the New York Giants, Robinson announced his retirement in the January 1957 issue of Look magazine. In the article, Robinson claimed that his body had passed its prime and could no longer perform at the major league level. He finished with a .311 career average and 19 career steals of home--the most by any player in the post-World War II era. Soon after his playing days were over, Robinson's health declined dramatically. He had to begin receiving insulin shots for diabetes and at one point went into a diabetic coma. In his later years the diabetic condition would take away his sight in one eye and significantly reduce his sight in the other.

Stimulated Black Business Opportunities.

After his retirement Robinson became a successful businessman and active supporter of political causes, devoting many of his efforts to the pursuit of a better life for African Americans. He became a vice president in the Chock Full O'Nuts restaurant chain, whose restaurants employed many blacks. He also worked with the Harlem YMCA in New York City and was made chairman of the board of the Freedom National Bank, a project in black capitalism. He later became the head of a construction company that built housing for black families and was involved in other ventures that stimulated black participation in business. Refusing to compromise his values, Robinson rejected an offer of membership in a private golf club when he learned that some members had objected to accepting an African American member. Despite his fame, he pursued his golf game at public courses.

Politically Independent.

In the political arena, Robinson campaigned for Senator Hubert Humphrey's bid for nomination on the Democratic presidential ticket in 1960. Then, despite objections from fellow Democrats, he switched parties to work for Richard Nixon in the presidential campaign because he felt that Nixon had helped support civil rights causes. Continuing to plot his own course, Robinson resigned his position as special assistant for community affairs on Republican Governor Nelson Rockefeller's staff in 1968 to once against campaign for presidential-hopeful Hubert Humphrey.

Elected to Cooperstown.

Robinson was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, his first year of eligibility. Even then he was surrounded by controversy, as fellow electee Bob Feller said that he didn't want to enter the Hall at the same time as Robinson. At his induction, Robinson called up three people from the audience to stand with him as he accepted the honor: his mother, his wife, and Branch Rickey. Robinson's respect and admiration for Rickey had never waned. He knew how important Rickey had been at helping blacks enter mainstream sports in the United States. When Rickey died in 1965, Robinson complained about the low number of blacks who had come to the funeral. According to The New York Times Book of Sport Legends, Robinson said, "I considered Mr. Rickey the greatest human being I had ever known."

Son Killed in Auto Accident.

Perhaps the cruelest blow to Robinson occurred in 1971, when his son, Jackie Jr., died in a car accident. Three years earlier, the younger Robinson had been arrested for heroin possession due to an addiction he had developed--and later kicked--after being wounded in Vietnam. Jackie Sr. remained active in national campaigns against drug addiction right up to his own death.

Chronic Health Problems Take Their Toll.

By the early 1970s Robinson was still pressing for more integration in sports, and most of all wanted to see a black manager in professional baseball. In 1974, Frank Robinson became the first black major league manager, taking over the reins of the Cleveland Indians. Robinson received a special honor in 1972, when he was asked to throw out the ball to open the second game of the 75th World Series at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati. Although still in his early 50s, Robinson was in shaky physical health by this time. He had survived one heart attack, and his body had suffered from years of diabetes and high blood pressure. Less than two weeks after his ceremonial toss at the World Series, he collapsed at his home in Connecticut and died later that day. His funeral at Riverside Church in New York City attracted more than 2,500 people, including many celebrities and political dignitaries. Thousands lined the streets as Robinson's body was taken to Brooklyn for burial.

Civil Rights Trailblazer.

Jackie Robinson always went his own way, answering to his own instincts and refusing to be swayed by those who objected to his choices. He never took for granted his role as a trailblazer in the integration of sports and the opening of opportunities for blacks in the United States. As Frommer wrote, "Just as Robinson had placed his stamp on baseball, his historic role in baseball had stamped him." By being a man with incredible physical skills, mental fortitude, and competitive fire who arrived in the right place and at the right time in history, Robinson had a major impact on the black struggle for equality in the 20th century.