Iva Toguri biography

Date of birth : 1916-07-04

Date of death : 2006-09-26

Birthplace : Los Angeles, California, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-09-13

Credited as : citizen, Pearl Harbor,

0 votes so far

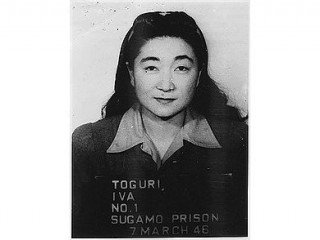

Toguri was visiting Japan when that country bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, launching the United States into the war. Trapped in Japan, she was forced by the Japanese government to announce on English-speaking radio programs. Toguri spent her later years in Chicago and in January of 2006, eight months before her death, she received a citizenship award from a World War II veterans committee.

Toguri was born on July 4, 1916 Independence Day in the United States. Her Japanese immigrant parents raised her in what was then the mostly white city of Compton, south of Los Angeles. Toguri spoke little Japanese. She joined the Girl Scouts, attended a Methodist church, enjoyed big bands "and hated sushi," the Los Angeles Times ' Nelson wrote. She graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles, with a degree in zoology in June of 1941. Toguri tabled her medical ambitions to help care for her dying aunt in Japan. Her six-month stay was nearly over when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7.

Toguri's relatives, under pressure from neighbors, made her leave their home. Branded an enemy alien, she asked Japanese officials to imprison her with other U.S. nationals. Instead, with the Japanese government looking for a woman with an American accent to broadcast propaganda, she was forced to work for Radio Tokyo's "Zero Hour" show. Toguri was actually one of a dozen or so female announcers that U.S. soldiers nicknamed "Tokyo Rose." The persona was used to demoralize U.S. soldiers through false battle reports and taunting.

Toguri, however, never used that handle, instead calling herself "Orphan Ann" (the "Ann" was short for announcer). "While the Japanese were trying to use the broadcasts as propaganda, an Australian prisoner of war who wrote the shows Toguri did said the programs were intended as 'straight-out' entertainment," Trevor Jensen wrote in the Chicago Tribune . Comedy skits and newscast introductions were standard fare for Toguri, which Adam Bernstein of the Washington Post described as "a raven-haired woman with a tender moon face."

After a former Radio Toyko employee identified Toguri as Tokyo Rose, U.S. occupying forces held her for about a year after the war ended, then released her. By then she had married Felipe D'Aquino, a Portuguese national who also worked in the radio industry. But Toguri was rearrested because of public outcry led by gossip broadcaster Walter Winchell. "Back home, a myth of war had gone Hollywood," Nelson wrote in the Los Angeles Times . The 1946 movie, Tokyo Rose , presented the main character as a "sultry, malevolent traitor," Nelson wrote. "Pressure steadily built on the administration of President [Harry S] Truman to 'make an example of somebody' in 1948," Nelson added. Following her secret arrest in Japan, she was tried on eight counts of treason and convicted in 1949. During the trial, witnesses testified that she said over the air: "Orphans of the Pacific, you really are orphans now. How will you get home now that all your ships are lost?," according to the New York Times ' Richard Goldstein. She served six years of her ten-year sentence in West Virginia and received a $10,000 fine upon her release in 1956. Years later, Toguri said she felt like a scapegoat amid racial hysteria. "It was eenie, meenie, minie and I was moe," she said in 1976, according to the Los Angeles Times ' Nelson.

After her release, Toguri settled in Chicago, running the J. Toguri Mercantile Company with her father and other relatives. There, she was a very private person. "She had a hard outer shell, and you could understand why," Thomas Tunney, a Chicago Alderman and owner of a restaurant which Toguri frequented, told the Chicago Tribune 's Jensen.

The Kurtis documentary aired on a Chicago CBS-TV affiliate in 1969 Toguri's first public airing of her plight and a groundswell of support for her snowballed a few years later. Ronald Yates of Chicago Tribune reported in a special series in 1976 that two key witnesses perjured themselves under intense pressure. Morley Safer followed with a 60 Minutes segment early in 1977. President Gerald R. Ford, in one of his final acts in January of 1977, pardoned Toguri and restored her citizenship. "I have always maintained my innocence this pardon is a measure of vindication," Toguri said, according to the New York Times ' Goldstein.

Toguri and her husband divorced in 1980. While living in Chicago, Toguri helped Japanese students and young entrepreneurs with funding. Tunney, who had real estate dealings with Toguri during the 1980s, respected her as a "hard-nosed businessperson," he told the Chicago Tribune 's Jensen. She lived in Chicago's Uptown neighborhood, on the North Side, and communicated little with neighbors.

In January of 2006, the World War II Veterans Committee presented to Toguri the Edward J. Herlihy citizenship award, named in honor of the wartime newsreels announcer. She accepted her medal during a private ceremony at Yoshi's Cafe in Chicago. "She was tearful and overcome with emotion," Veterans Committee president James Roberts said in the Chicago Tribune . "As I understood it, it was part of a long process of vindication."

Toguri died on September 26, 2006, of complications from old age in Chicago, Illinois. She was 90. Toguri had requested no memorial or funeral.