Ishi biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : 1916-03-25

Birthplace : Sacramento River Valley

Nationality : Native American

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2011-07-05

Credited as : Yana people, member of Yahi, Indian

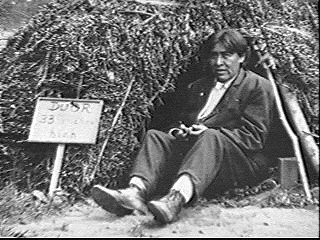

The last surviving member of the Yahi tribe of the Yana Indians, Ishi was regarded as the last aboriginal Indian to survive in North America when he wandered into Oroville, California, on August 29, 1911. The middle-aged Ishi was regarded as both a public curiosity from the Stone Age as well as the source of vital anthropological data on Native American life prior to European settlement. By all accounts an outgoing yet dignified man, Ishi lived in a museum at the University of California at San Francisco for five years, where he was avidly studied by linguist Thomas T. Waterman and anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber.

In 1916 Ishi died of tuberculosis. Against his own wish to be cremated immediately upon his death, an autopsy was performed on Ishi and his brain was sent to the Smithsonian Institute for storage. Although officials at the Smithsonian later denied having Ishi's brain, Native American activists began a campaign in the 1990s for the return of the final Yahi's remains so that they could be given a traditional Yahi burial. Citing the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which stipulated that any Native American remains in federally funded collections must be returned to their descendants, the activists were finally successful in forcing the Smithsonian to turn over Ishi's brain to the Redding Rancheria and Pit River Tribes, the closest surviving descendants of Ishi's Yahi tribe. Together with the rest of Ishi's remains, which had been cremated and buried in Colma, California, the two Indian groups finally buried Ishi in his ancestral home land around Deer Creek Canyon in north-central California in August of 2000.

Ishi's sudden appearance in Oroville in 1911 stunned the area's residents, who had assumed that members of the Yahi tribe had long since died off. As the southernmost branch of four main tribes of the Yana Indians, who resided around the Sacramento River Valley in north-central California, the Yahi inhabited the area around Mill Creek and Deer Creek just south of Mount Lassen, about 100 miles north of the present-day state capital of Sacramento. In the early 1800s, possibly as many as 3,000 Yana Indians lived in the Sacramento River Valley; however, their lives were upturned with the California Gold Rush of 1849, when thousands of prospectors streamed into northern California in search of fortune. The Yahi had already clashed with previous settlers to the Valley and had a reputation as fierce and stealthy fighters when challenged. Thus, the rough-and-ready '49ers, as the prospectors and their families were called, were determined to exterminate the tribe as they settled the area. In addition to epidemics of previously unknown diseases such as measles, smallpox, and tuberculosis, the brutal warfare waged between the two troops reduced the Yana population by about 95 percent by the 1890s.

Ishi was probably born around 1860, at a time when the Yahi faced the last of their battles with settlers around the Sacramento River Valley. His father was killed in one of the last attacks around 1865; after another confrontation in 1870, an estimated 20 surviving Yahi withdrew into the wilderness. By 1880 the Yana's home land was largely settled by white landowners, although stretches of forbidding territory in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains remained largely unexplored. Instead of driving off the settlers with violence, the Yahi instead inhabited the rocky territory, which effectively hid them from view. Surviving by hunting and fishing in their traditional manner, they added to their stock of food and clothing by occasionally raiding a settler's cabin for supplies. One such occurrence happened when Ishi and the other Yahi made a raiding party on a cabin on Dry Creek in April of 1885. The owner of the cabin encountered a group of four Indians leaving with some of his family's old clothes and let them leave with the items without interfering. Later that year, the settler found two Yana baskets left in his cabin, perhaps a sign of thanks for his generosity.

By 1894 only about five Yahi tribe members were left, including Ishi, his mother, a female relative that Ishi identified as his sister, and an elderly man. These survivors established a small encampment with two dwellings at the confluence of Deer Creek and Sulfur Creek in a clearing well hidden from any intrusions. Indeed, it was well over a decade before any outsiders came across the camp, although the Yahi themselves were spotted at times over the years. In 1908 engineers for the Oro Light & Power Company undertook a land survey of the area in preparation for building a dam there. On November 8, 1908, two surveyors returning to their camp after a day of work unexpectedly encountered Ishi as he was fishing in Deer Creek. Ishi immediately scampered off, and most of the other surveyors refused to believe that an Indian would still be living in the area. The next day the company's guide decided to investigate; as he proceeded up Deer Creek, he was almost hit by an arrowhead launched by an unknown shooter. Returning with the rest of the engineering company, the men soon found the Yahi encampment, which had just been abandoned except for one old woman who could not walk. Some of the men took a few items they found in the camp as souvenirs, and they left the old woman alone. Troubled by his conscience, the guide returned to the camp again the next day to see if the old woman could be helped; when he reached the camp, she had disappeared.

Ishi himself eventually described the arrival of the surveying party that led to the final dissolution of the Yahi tribe. With their camp about to be discovered by the engineers, Ishi ran in one direction while his sister accompanied the elderly man in the other direction, leaving Ishi's elderly mother behind. After the engineers left, Ishi returned to take his mother away; she died a short time later, although Ishi was vague about the details. He never saw his sister and the old man again; because they never appeared at any of the group's common meeting areas, he assumed that they had fallen into Deer Creek and drowned or met some other fatal encounter. With the loss of his tribe, Ishi entered a period of mourning and burned off his hair. He remained alone in the wilderness for the better part of three years.

Close to starvation and exhaustion, Ishi finally decided to surrender himself to the settlers that had largely destroyed his people's existence. On August 29, 1911, he walked to a slaughterhouse near Oroville, California, and gave himself up to the men who worked there. The Butte County sheriff was quickly summoned; not knowing what to do with the Indian, he took Ishi to the county jail for his own safety. News of the appearance of an aboriginal Yahi Indian, years after the tribe was assumed to have been decimated, immediately made headlines around the state. One person who took particular notice of the stories was University of California linguistics professor Thomas T. Waterman, who traveled to Oroville as soon as he heard the reports.

Waterman's arrival in Oroville was fortuitous, as he was one of the foremost authorities on the Yana Indians. Taking a list of Yana words with him, Waterman attempted to communicate with Ishi without success, until he pointed to the wooden frame of Ishi's bed and said the Yahi word for wood. Gradually, the two discovered a few words that were mutually intelligible, and the arrival of a northern Yana Indian, who knew a few more words of Yahi, helped Ishi become more outgoing. Although the language barrier made it difficult to reveal much of his life history at first, Waterman recognized that Ishi was indeed the last surviving member of the Yahi tribe. Even his actual name was surrounded in mystery; in accordance with Yahi custom, Ishi never spoke his own name or revealed it to any outsider; instead, he took the name "Ishi," meaning "man" in the Yahi language, and he was known by the epithet for the rest of his life.

From September 1911 until his death in 1916, Ishi made his home on the grounds of the University of California at San Francisco. He lived in a room in the university's anthropological museum and performed a few janitorial tasks in exchange for a modest stipend. Under the guidance of Professor Alfred L. Kroeber, Ishi learned a few hundred words of English and adapted many habits from his new surroundings. Ishi immediately started to wear long pants and dress shirts, although he took to wearing shoes only after living at the museum for several months. He patronized the school's cafeteria and enjoyed eating most of the new foods he encountered to the extent that he became somewhat overweight. Although he avoided the company of women in accordance with the social mores he had learned as a Yahi, Ishi was regarded as an outgoing and even-tempered person who quickly charmed anyone he met.

Although a genuine friendship likely evolved between Ishi and his academic mentors, professors Waterman and Kroeber also viewed Ishi as an invaluable source of information on Native American ways that had been obliterated by white settlement. As such, the men exhaustively studied Ishi's language, beliefs, and material culture. Ishi was also put on display at the museum and attracted thousands of people who watched him make bow-and-arrow sets, arrowheads, and traditional Yahi dwellings. More recent academics have criticize Ishi's objectification as a museum attraction, although most agreed that such intrusions into Ishi's life were not out of line with practices of the period. Indeed, during his time at the museum, Ishi gladly shared information about the Yahi, even though he was hesitant to discuss the painful loss of his family. In the spring of 1914, Ishi returned to his ancestral home land one last time on an expedition arranged by the university. There he showed his companions a range of hunting and fishing skills, and his academic colleagues were glad to take advantage of the opportunity to record Ishi's activities for posterity.

Like many Native Americans entering a foreign society, Ishi was plagued by recurring illnesses, particularly colds. In the winter of 1915, his illness deepened into tuberculosis. By the time the correct diagnosis was made, Ishi had weakened considerably and he died at the university on March 25, 1916. It was estimated that he was in his mid-fifties.

Prior to his death, Ishi expressed an adamant opposition to being autopsied; he had witnessed surgeries at the university's medical school and remained skeptical of Western medicine. With Kroeber absent at the time of his death, however, Ishi's brain was removed and preserved. Although upset with this action, Kroeber sent the brain to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C., where it sat, undisturbed, for several decades. With the passage of the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, however, several Native American groups began to press for a full inventory of Indian artifacts and remains in federally funded collections, and requested that, per the act, any such objects be returned to their rightful tribes. In 1997 the case of Ishi became a cause celebre when several California tribes publicized the Smithsonian's refusal to admit that they possessed Ishi's remains.

The following year, the institute acknowledged that it still had Ishi's brain and entered discussions to decide which tribes were the closest legitimate descendants to the extinct Yahis. In August 2000, the Smithsonian turned over Ishi's brain to two groups of northern California Indians, the Redding Rancheria and Pit River tribes. The two groups collected the rest of Ishi's cremated remains, which had been buried in the city of Colma, California, and made a final burial in Deer Creek Canyon. Eighty-five years after his death, Ishi was finally laid to rest in accordance with his own wishes. Although Ishi's final burial was a fitting conclusion to his own story, the repatriation of other Native American remains and artifacts continued to be a contentious topic. A decade after its passage, most museums subject to the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act had yet to comply with its mandate.