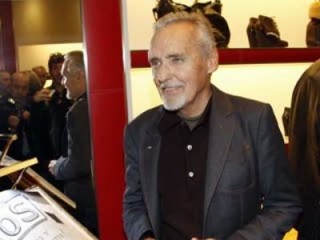

Hopper Dennis biography

Date of birth : 1936-05-17

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Dodge City, Kansas, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-06-04

Credited as : Actor screenwriter and director, ,

0 votes so far

Dennis Hopper is one of the film medium's most successful and influential independent artists. He grew up on a farm in Kansas, far away from the frenetic movie industry. "Wheat fields all around, as far as you could see," he told Mark Goodman in a 1978 New Times profile. "No neighbors, no other kids. Just a train that came through once a day. I used to spend hours wondering where it came from and where it went to." Around age five, after accompanying his grandmother into town to sell eggs, Hopper was treated to his first visit to the cinema. The experience was exhilarating. "Right away it hit me--the places I was seeing on the screen were the places the train came from and went to!," he recounted. "The world on the screen was the real world, and I felt as if my heart would explode I wanted so much to be a part of it."

By age thirteen, when his family moved to San Diego, Hopper was already considering a career in the arts. "I wanted to be an artist, poet, something that would last," he recalled in New Times. "Guys like Van Gogh, Gaugin, Rimbaud, they gave me faith because their lives were tragic ruins, but they would still be remembered centuries later."

In San Diego Hopper studied acting and performed in Shakespearean productions at the city's Old Globe Theater. At age eighteen he signed a film contract with Warner Brothers. His first roles were in "Rebel Without a Cause" and "Giant," two works featuring James Dean, whose acting ability astounded Hopper. "He was the most talented person I've ever seen," Hopper contended. "I finally grabbed him one day and said, `Hey, man, you're so much better than me I don't know what's happening.' " The two actors became intimate friends before Dean's fatal automobile crash in 1955.

Early in his career Hopper developed a reputation as a surly and often uncooperative performer. "I wouldn't take direction from anyone," he told People in 1983. "I got away with it for a while." He sabotaged his fourth film, "From Hell to Texas," by forcing director Henry Hathaway to waste three days filming one of Hopper's scenes eighty-seven times. After completing the scene a frustrated Hathaway informed his young actor, "You'll never work in this town again."

Hopper worked only infrequently for the next several years, appearing most notably in "Night Tide," a strange and often eerie film in which he played a sailor involved with a woman who believed she was mermaid. Instead of working regularly, Hopper pursued his interest in European cinema. "I liked the idea of hand-held cameras and open spaces," he remembered. "We were locked into four walls in those days. Truffaut and Godard taught us to bolt the studio doors and go out and shoot."

In 1961 Hopper married Brooke Hayward, daughter of showbusiness agent Leland Hayward and actress Margaret Sullavan. Hopper's marriage, oddly enough, led to the rejuvenation of his career, for former nemesis Hathaway was an admirer of Sullavan and so offered her new son-in-law a role in the western "The Sons of Katie Elder." But though Hopper's career then prospered, his marriage failed, perhaps hitting its nadir when he delivered a crushing karate chop to his wife's face. "I'm not sure I really broke her nose," he later said.

After his marriage ended Hopper met with fellow actor Peter Fonda, with whom he had worked in "The Trip," and conceived a project which they would act in and make without help from the major studios. They collaborated with Terry Southern to write "Easy Rider," a script about two young men who use their profits from a heroin deal to finance a crosscountry trip on motorcycles.

Filming "Easy Rider" proved rather trying for novice director Hopper. He frequently clashed with Fonda (who eventually armed himself and traveled with a bodyguard) and also fought with a cameraman, striking him with a karate blow after the worker threw a television at him. Furthermore, Hopper loathed motorcycles. "I can't stand the... things," he confessed years later. "Like... everyone thought I was a heavy biker, right? I was terrified of that bike."

When "Easy Rider" was released in 1969 it showed little evidence of the behind-the-scenes turmoil that plagued its production. Instead, Hopper's freewheeling direction--alternating sweeping panoramas with jerky, hand-held camerawork--worked with jarring editing, a rock music score, and Laszlo Kovacs's impressionistic cinematography to create a disturbing view of life in America, one that Richard Corliss described in the New York Times as "an ode to the beauty and impossibility of being free in these United States."

Some critics protested the depiction of drug dealers as heroes in "Easy Rider," but many nonetheless conceded that the finale, in which the dealers-turned-bikers (played by Fonda and Hopper) are gunned down by Southern roughnecks, was powerful and unsettling. Vincent Canby wrote in the New York Times that the two figures "run smack into the kind of nightmare America that murdered [civil rights worker] Viola Liuzzo." He found the murders particularly disturbing because they were motivated by a "fear of innocence and a dread of freedom that cannot even be tied to socio-political action."

"Easy Rider" also proved that a low-budget, independent film could be both an artistic and commercial success, an accomplishment that some critics deemed more impressive than its value as commentary. Canby wrote that "the most exciting thing about `Easy Rider' is neither content nor style nor statement, but the fact that it was made for less than $500,000... by young men working outside the moviemaking establishment, and that it is aparently reaching a large audience." Corliss hailed "Easy Rider" as an example of the new, "revolutionary" films--independent works with political content that threatened to rival mainstream Hollywood productions. He wrote of "Easy Rider" and other, thematically similar works, "They are angry, engaged, bold--and financially successful, a crucial factor that almost ensures the continuation of what may become a new movie genre: The Revolutionary Film."

The success of "Easy Rider" brought Hopper both immediate wealth and acclaim as an artist, earning him an award for best first film at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival (though the New York Times reported that only one other film competed for the prize). Encouraged by Hopper's success, Universal provided him with a budget of nearly one million dollars--almost twice the amount spent on "Easy Rider"--to finance "The Last Movie," his second venture as actor-writer-director.

"The Last Movie" is the story of an American film crew and its effect on a Peruvian village while making a western. In the film Hopper contrasts the two cultures, emphasizing the corrupting and frequently destructive nature of American life. He also explores levels of reality with the film, shifting the narrative back and forth between events in "The Last Movie" and those in the film-within-the-film. In some scenes Hopper even disrupts the actual narrative, revealing his moviemaking process by mugging before the cameras or introducing flash frames that announce "scene missing."

Hopper also acts in "The Last Movie" as Kansas, a stunt man who chooses to remain in Peru and search for gold after the crew departs for home. Here Hopper broadly contrasts Kansas's frantic and frequently overbearing behavior with the more modest manner of the villagers. Eventually Kansas is drawn into a series of bizarre games that culminate in a religious ritual in which the natives, unaware that Kansas was only acting when he "died" during a shoot-out scene for the filmmakers, attempt to re-enact his "resurrection" by actually crucifying him as part of an orgiastic Passion Play.

While filming "The Last Movie" Hopper was relatively free of the difficulties he had endured directing "Easy Rider." He had written the original script years earlier, in 1965, while working in Hathaway's "The Sons of Katie Elder." He then re-worked the final script with Stewart Stern, who received sole credit for the screenplay--Hopper and Stern are listed as collaborators on the screen story. Once in Peru Hopper worked efficiently, if unpredictably. "You know, I don't think anyone realizes what I'm doing down here," he said to Alix Jeffry in the New York Times. "In fact, I'm not sure I do either."

Despite Hopper's uncertainty, filming "The Last Movie" took only eight weeks. The editing process, however, occupied him for more than a year. When he finally submitted his approved version to Universal, the studio heads were aghast at its disjointed narrative. They demanded that Hopper re-edit it, but he refused, having had rights for final editing stipulated in his contract.

After "The Last Movie" premiered to acclaim at the Venice Film Festival, where it won an award for best film, Hopper's steadfastness seemed justified. But when the film was released in the United States, critics decried it as self-indulgent, inexplicable folly. Canby called it "an extravagant mess" and declared that Hopper's "thoughts have all of the impact of revelations written down during an acid trip." Time's Stefan Kanfer was equally vehement in his criticism, deeming the film "puerile" and lampooning Hopper's apparent self-indulgence. "Ignoring the plot," wrote Kanfer, "the director presents a gallery of his favorite art works: Waterfall With a Distant View of Dennis; Effect of Dennis Through Peruvian Haze; Ruins of Dennis by Twilight; and his favorite: Dennis as the Universal Infant."

Universal refused to release "The Last Movie" outside the United States in the wake of its domestic demise. The studio purchased the unused footage, reportedly to make a film for television. Years later, Hopper remained bitter about the experience, though he attributed the film's demise to his own naivete. "If they don't explain the game to you, what a schmuck you can be," he said in New Times, adding that his sole regret "is that nobody taught me how to play."

Throughout the remainder of the 1970's Hopper was unable to obtain funding for his own projects. He worked instead as an actor, appearing in foreign productions such as Spain's "The Sky Is Falling" and Australia's "Mad Dog." His personal life was also in a state of constant upheaval. His marriage to pop singer and actress Michelle Phillips ended after only eight days when Hopper, in a telephone conversation, expressed his need for her and she responded, "Have you considered suicide?" Then a third marriage, to actress Daria Halprin, also failed. Hopper accelerated his habitual use of drugs and alcohol, daily consuming three grams of cocaine, a half gallon of rum, and more than a case of beer. Photography, which had once been a fruitful avocation for Hopper--his work was exhibited in several museums--had long since ceased to be a channel for his creativity.

By the late 1970's, though he was still unwanted as a writer-director, Hopper found renewed popularity as an actor. He gave a compelling performance as the amoral Tom Ripley in German filmmaker Wim Wenders's "The American Friend." Here Hopper portrays a pathetic, lonely American who brings chaos to a framemaker's life in retaliation for a refused handshake. Canby praised Hopper for playing Ripley "with effectively insidious self-assurance."

Hopper was also cited by critics for his performance as a hyperactive photographer in Francis Ford Coppola's Vietnam epic "Apocalypse Now." Hopper's character is a raving disciple of Colonel Kurtz, a cold-blooded American officer conducting his own war in Cambodia. Newsweek's Jack Kroll declared that Hopper acts the "freaked-out photo-journalist" with "perfect zonkitude."

In 1980 Hopper finally got another opportunity to direct when he replaced the first director in "Out of the Blue," a film in which he was originally scheduled only to act. Working from a screenplay by Leonard Yakir and Brenda Nielson, Hopper shaped "Out of the Blue" into a bizarre portrait of American life. The film centers on a father-daughter relationship: The father is just out of prison, where he served a sentence for killing several children (he accidently crashed his truck into a schoolbus while fondling his daughter); the daughter, who worships punk singer Johnny Rotten, avoids her mother (a drug addict) and passes time placing herself in dangerous situations and attempting to get out of them. Perhaps the film's most disturbing scene is one in which the drunken father awakens his daughter--"It's Daddy, man. I just want to say goodnight"--and watches a friend rape her.

When "Out of the Blue" received its belated American release in 1983, critics praised it as a powerful and disturbing work. Village Voice's J. Hoberman called it an "unrelenting, downbeat tale of family madness" and found it far superior to other contemporary films on abuse and delinquency. More impressed was Nation 's Robert Hatch, who described the film as "a remorseless study of child abuse, and a savage attack on the pollutions of modern society."

Since completing "Out of the Blue" Hopper has worked exclusively as an actor. He has also quit drinking, an act due, perhaps, to a strange incident in Cuernavaca, Mexico, where Hopper was working in "Jungle Warrior." "I thought I was being attacked by snakes," Hopper said in People. "I wanted to die naked. I ran out in the middle of the night and I became a solar system." After completing his nude jaunt Hopper was found twenty miles away by police. He blamed his action on LSD that he suspects was slipped into tequila someone mysteriously left in his hotel room. Since then Hopper has joined Alcoholics Anonymous and claims to be "enjoying reality for a change." Summing up his often turbulent past he adds: "What can I say? I was a fun guy."

WRITINGS:

* (With Peter Fonda and Terry Southern; and director) Easy Rider (screenplay; released by Columbia, 1969), New American Library, 1969.

* Out of the Sixties, Twelvetree Press (Pasadena, CA), 1986.

Also author of screen story (with Stewart Stern) of "The Last Movie," Universal, 1971, and cowriter of "The American Dreamer," EYR, 1971.