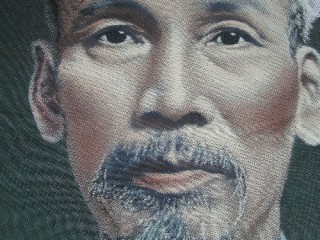

Ho Chi Minh biography

Date of birth : 1890-05-19

Date of death : 1969-09-03

Birthplace : Kim Lien, Vietnam

Nationality : Vietnamese

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-06-20

Credited as : Politician, Marxist revolutionary leader,

The Democratic Republic of Vietnam, or North Vietnam, the little Asian country that held two leading Western powers—France and the United States—at bay after the end of World War II, was founded and proclaimed by Ho Chi Minh in 1945. In spite of his shrewdness, the frail, little

Ho was born Nguyen That Thanh on May 19, 1890, in the village of Kim Lien, province of Nghe An, central Vietnam, into a family of scholar-revolutionaries, who had been successively dismissed from government service for anti-French activities. At the age of 9 Ho and his mother, who had been charged with stealing French weapons for the rebels, fled to Hue, the imperial city. His father, constantly persecuted by the French police, had left for Saigon. After a year in Hue, his mother died. Young Ho returned to Kim Lien to finish his schooling. At 17, upon receiving a minor degree, Ho journeyed to the South, where he spent a brief spell as an elementary school teacher.

At the news of the first Chinese revolution, which broke out in Wuchang, the fiercely patriotic Ho left for Saigon to discuss the situation with his father. It was then decided that Ho should go to Europe to study Western science and survey the conditions in France before embarking upon a revolutionary career. Unable to finance such a trip, Ho nevertheless managed to obtain a job as a messboy on a French liner.

By the end of 1911 Ho began his seaman's life, which took him to the major ports of Africa, Europe, and America. As World War I broke out, Ho bade farewell to the sea and landed in London, where he lived until 1917, taking on odd jobs to support himself. It was here that Ho cultivated contact with the Overseas Workers' Association, an anticolonialist and anti-imperialist organization of Chinese and Indian seamen.

In 1917 Ho departed for France. He settled in Paris, working successively as a cook, a gardener, and a photo retoucher. Ho spent half his time reading, writing, trying to gain French sympathy for Vietnam, and organizing the thousands of Vietnamese, who were either serving in the French army or working in factories. He also joined the French Socialist party and attended various political clubs.

Distressed by the Western powers' indifference toward the colonies both during and after the Versailles Conference in spite of the Fourteen Points of U.S. president Woodrow Wilson, Ho, whose only interest up to that time had been Vietnam's independence, began to drift toward Soviet Russia, the champion of the oppressed peoples. At its Tours Congress in 1920, the French Socialist party split on the colonial issue: one wing remaining indifferent to the problems of the colonies and another advocating their immediate emancipation in accordance with Lenin's program. Ho sided with the latter faction, which seceded from the parent organization and formed the French Communist party.

In 1921 Ho organized the Intercolonial Union, a group of exiles from the French colonies which was dedicated to the propagation of communism, and published two papers, one in French, Le Paria, and one in Vietnamese, the Soul of Vietnam, which carried emotional articles denouncing the abuses of colonialism. His most important work, French Colonialization on Trial, was also written during this period.

In November-December 1922 Ho attended the Fourth Comintern Congress in Moscow. In October 1923 he was elected to the 10-man Executive Committee of the Peasants' International Congress. Late in 1923 Ho went to Moscow, where he absorbed the teachings of Marx and Lenin. Two years later he arrived in Canton as adviser to Soviet agent Mikhail Borodin, who was then adviser to the Chinese Nationalists.

Passing for a nationalist, Ho brought the Vietnamese emigres in Canton into a revolutionary society called Youth and organized Marxist training courses for his young fellow countrymen. The Youth members were the nucleus of what was to be the Indochinese Communist party. Those who refused to obey Ho's orders were severely punished; Ho would forward their names to the French police force, which was always eager to put them behind bars. Ho also set up the League of Oppressed Peoples of Asia, which was to become the South Seas Communist party.

In April 1927, as the Chinese Nationalists broke with their Soviet advisers, Ho had to flee to Moscow. Subsequently, he received a brief assignment to the Anti-Imperialist League in Berlin. In 1928, after attending the Congress against Imperialism in Brussels, Ho journeyed to Switzerland and Italy, then turned up in Siam to organize the Vietnamese settlers and direct the Communist activities in Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. Early in 1930 Ho went to Hong Kong, where on February 3 he founded the Indochinese Communist party.

A year later Ho was arrested by the Hong Kong authorities and found guilty of subversion. Thanks to a successful appeal financed by the Red Relief Association, Ho regained his freedom. He immediately left for Singapore, where he was again arrested and returned to Hong Kong. Ho obtained his release by agreeing to work for the British Intelligence Service. Back in Moscow in 1932, Ho underwent further indoctrination at the Lenin School, which trained high-ranking cadres for the Soviet Communist party. In 1936 Ho returned to China to take control of the Indochinese Communist party.

In February 1941 Ho finally crossed the border into Vietnam and settled down in a secure hideout in a remote frontier jungle. With a view to bringing all resistance elements under his control, winning power, then eliminating all competitors and creating a Communist state, Ho founded an independence league called the Viet Minh, whose alleged program was to coordinate all nationalist activities in the struggle for independence. (At this time Ho adopted the name Ho Chih Minh—"Enlightened One.") While the Viet Minh included many nationalists, most of its leaders were seasoned Communists.

In August 1942 Ho went back to China to ask for Chinese military assistance in return for intelligence about

the Japanese forces in Indochina. The Chinese Nationalists, who had broken with the Communists and been disturbed by the Viet Minh activities in both Vietnam and China, however, arrested and imprisoned Ho on the charge that he was a French spy. After 13 months in jail Ho offered to put his organization at the Chinese service in return for his freedom. The Chinese, who were in desperate need of intelligence reports on the Japanese, accepted the offer. Upon his release Ho was admitted to the Dong Minh Hoi, an organization of Vietnamese nationalists in China which the Chinese had set up with the hope of controlling the independence movement. Ho repeatedly offered to collaborate with the United States intelligence mission in China, hoping to be rewarded with American assistance.

As the war approached its end, Ho made preparations for a general armed uprising. Following Japan's surrender, the Viet Minh took over the country, ruthlessly eliminating their nationalist opponents. On Sept. 2, 1945, Ho proclaimed Vietnam's independence. In vain he sought Allied recognition. Faced with a French resolve to reoccupy Indochina and determined to stay in power at any cost, Ho acquiesced in France's demands in return for French recognition of his regime. The French, however, disregarded all their agreements with Ho. War broke out in December 1946.

Many nationalists, while aware of the Communist nature of Ho's government, nevertheless supported it against France. The war ended in July 1954 with a humiliating French defeat. An agreement, signed in Geneva in July 1954, partitioned Vietnam along the 17th parallel and provided for a general election to be held within 2 years to reunify the country. Because of mutual distrust, absence of neutral machinery to guarantee freedom of choice, and opposition of South Vietnam and the United States, the scheduled election never took place.

Ho, who had hoped that a larger population under his control, a Communist-supervised election in the North, and a more or less free election in the South would produce an outcome favorable to his regime, became greatly frustrated. He ordered guerrilla activities to be resumed in the South. Regular troops from the North infiltrated the South in increasing numbers. The United States, correspondingly, increased military assistance, sent combat troops into South Vietnam, and began a systematic bombing of North Vietnam.

Ho refused to negotiate a settlement, hoping that American public opinion, as French public opinion had done in 1954, would force the United States government to sue for peace. Apprehensive that his lifework might be destroyed and anxious to spare North Vietnam from further devastating air attacks, Ho finally agreed to send his representatives to peace talks in Paris. As the antiwar feeling mounted in the United States and other countries, Ho stalled, intent on obtaining from the conference table what he had failed to get on the battlefield. While the talks were dragging on, Ho died on Sept. 3, 1969, without realizing his dream of bringing all Vietnam under communism.