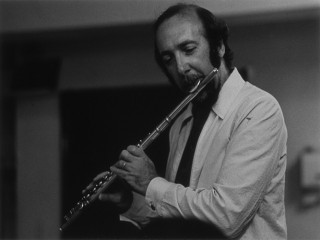

Herbie Mann biography

Date of birth : 1930-04-16

Date of death : 2003-07-01

Birthplace : Brooklyn, New York, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-12-12

Credited as : jazz flutist, played tenor saxophone, "Hijack" single

0 votes so far

Not many musicians can claim to have single-handedly created the style of music for which they are famous. Among the select group who legitimately can is Herbie Mann, a seminal figure in the American jazz scene of the 1960s and '70s. Largely on the strength of his talent for improvisation and willingness to experiment, Mann formulated a jazz style for the flute, raising to the rank of lead an instrument which prior to his arrival had been limited to a minor role in the jazz pantheon. In the process, he was to garner a reputation as one of the most eclectic figures in the music world, readily mixing a wide range of styles from African to Brazilian, from Charlie Parker to disco, to create music that crossed boundaries in every sense of the word. Although his experiments did not always endear him to jazz critics, the result was a musical style that was indisputably his own.

Mann was born Herbert Solomon on April 16, 1930 in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Harry and Ruth Solomon. Musically inclined from an early age, his first concerts took the form of raucous banging on the kitchen pots and pans. His parents, driven to distraction, decided that young Herbert's energies would be channeled in a more fruitful direction by exposure to popular music; in 1939, his mother took him to see the then-reigning master of swing jazz, clarinetist Benny Goodman. The concert had the desired effect, as Mann, fascinated by the atmosphere and excitement of live performing, left off his drumming and took up the clarinet with enthusiasm.

Mann's talent for performing was immediately evident to his teachers and he progressed rapidly. As a teenager, he branched out into playing the tenor saxophone, an instrument that would come to dominate the post-World War II American music scene. For good professional measure, he also learned how to play the flute, a instrument used largely in studios as a backing double. Since flute playing was found almost solely on Latin jazz records, Mann gravitated toward listening to the luminaries of the Latin music scene like Tito Puente, Machito, Charlie Palmieri, or American stars who recorded with Latin musicians such as Charlie Parker.

But the tenor saxophone was Mann's first love, and his guide and inspiration was the dominant figure in the New York jazz scene of the late Forties, Lester Young. As was the case for many other young musicians of his generation, Mann was enthralled by Young's cool, almost low-key, highly melodic approach to rhythm and harmony. Mann carried his passion with him into the U.S. Army, serving overseas from 1948 to 1952, certain that upon returning to civilian life he would make an immediate name for himself as a tenor sax player. But when Mann arrived back in New York, he found that many others had had the same idea and the field was overcrowded with hungry young saxophonists roaming from gig to gig.

It was at this point that Mann's career took the left turn that would change his and many others' ideas about jazz permanently. In early 1953, a friend of his approached him with the news that a Dutch accordionist, Mat Matthews, was forming a group to record with a then-unknown singer named Carmen McRae, and needed a jazz flute player. Mann convinced the friend to put his name forward, even though Mann knew next to nothing about jazz flute playing--a style which had virtually no precedents in the American music scene up until then. In a neat bit of chicanery, in person Mann convinced Matthews to take him on, explaining that his flute was being repaired and he would learn the arrangements on the saxophone. By drawing on Latin music he had absorbed earlier, as well as imitating on the flute the mannerisms of such up-and-coming trumpet players such as Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie, Mann quickly improvised a playing style that would give him a distinct stage presence.

Following a two-year stint with Matthews, Mann's career slowly took off. Over the course of the 1950s, he passed through a succession of groups, recording extensively as a sideman while enlarging and embellishing his creative mastery of the flute. Just as his style had originally developed out of Latin jazz, he found himself more and more drawn to that idiom's percussive rhythms and raw emotive power, tendencies running counter to the prevailing trend in jazz of the time toward intellectualized, distant compositions. As he explained in a 1973 New York Times interview, "The audience I developed wasn't listening intellectually; they were listening emotionally." Eager to tap into this current, Mann formed an Afro-Cuban sextet in 1958 that featured, among other developments, four drummers backing him. For the next several years, a steady parade of some of the best drummers of the era, such as Candido, Willie Bobo, Carlos "Patato" Valdes, and the Nigerian phenomenon Michael Olatunji, would pass through Mann's group.

With this innovative new sound, Mann began to make a name for himself in the jazz world. His percussion-heavy ensembles, apart from the audience excitement they generated, also proved to be an excellent counterpoint to his flute, the drums creating a wall of background noise against which his solos stood out in sharp relief. It didn't hurt that he was performing in a style that was totally new to most of his listeners; as Mann put it in a Down Beat interview, "... there wasn't really anybody for the people to compare me to... anytime I'd run out of ideas, the drums got it." After recording several albums for Verve Records, Mann signed with a major label, Atlantic, releasing his first album, Common Ground, with them in 1960. In 1962, his live album Herbie Mann at the Village Gate was his first major hit, selling over half a million copies; a song from that release, "Comin' Home Baby," would place in the Top 30 on the pop charts.

In spite of success that most musicians would envy, Mann was still not completely satisfied. Latin music with its dominant two-chord harmonies proved monotonous and ultimately constricting; he wanted a style that would allow him to explore a wider range of melodic possibilities. In 1961, he became interested bossa nova--a musical phenomenon then little known outside of its native Brazil--after seeing the movie Black Orpheus. His curiosity aroused, Mann persuaded his manager to include him in an all-star tour heading down to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil's cultural center, and began jamming with local musicians almost from the moment he stepped off the plane. In this and subsequent tours, he would come in contact with some of the giants of Brazilian music, including Sergio Mendes, Baden Powell, and Antonio Carlos Jobim.

Brazilian music, with its combination of pulsing rhythms and beautiful, varied melodies and harmonies, was a revelation for Mann. Here was the style he was looking for that would allow his solos to soar through elaborate ranges of melody backed by multiple rhythm parts. On his return to the United States, his band became one of the first groups to play bossa nova and went on to record a number of albums with Brazilian musicians. One of these included an English version of the famed hit "One Note Samba," featuring the singing debut of the tune's composer, Jobim. Brazilian music, although not as commercially successful as some of the other musical idioms Mann would work in, remained an undercurrent to which he returned throughout the rest of his career; one of his most recent albums Opalescence, recorded in 1988, is a lyrical and evocative revisiting of contemporary Brazilian music.

Perhaps as important in terms of Mann's artistic horizons, his plunge into bossa nova seemed to have liberated him from the necessity of being associated with one specific "sound." From the early Sixties on, he would explore a wide variety of musical styles, grafting elements of Middle Eastern, pop, rock, R&B, reggae, soul, and disco music onto jazz to reach a wide audience. Although this approach did not please jazz critics, who often dismissed his work as lacking substance, Mann would string together a spectacular run of commercial successes. In the period 1962-1979, 25 of his recordings placed on the Top 200 pop charts; in 1970 alone, five of the 20 top-selling jazz albums bore the name Herbie Mann on the cover, an unprecedented convergence of hits for a jazz artist.

After bossa nova, the next style Mann gravitated toward was rhythm and blues. Fascinated by its improvisational possibilities, he went south to record in Memphis, Tennessee and Muscle Shoals, Alabama, exchanging ideas with and drawing inspiration from some of the greatest R&B studio musicians of the time. The result was Memphis Underground, a 1969 album that was to prove his second great hit of the decade. In 1971, Mann recorded another hit, Push Push, with guitarist Duane Allman, who, as was often the case for Mann, he had met during an impromptu jam in New York's Central Park. Mann's approach to recording and performing in this period was highly eclectic; he would throw together as many musicians with different backgrounds as possible in the hope that something interesting would emerge. At times the result, as one critic writing in Down Beat noted, was a jumble of sound that "looked like fun to do, but wasn't very pleasant to listen to."

In 1972, Mann stabilized his musical entourage by forming the group the Family of Mann, based around David Newman on tenor sax and flute, Pat Rebillot on keyboards, and a floating lineup of New York session players. Although in the first half of the decade he continued to explore jazz/rock fusion and dabbled in reggae, the burgeoning dance craze inevitably began to impact Mann's career. In 1974, his disco single "Hi-Jack," recorded with Cissy Houston and released 24 hours later, was a massive hit. Pressured by profit-minded executives at Atlantic to keep up the winning formula, Mann was deprived of his cherished freedom to experiment and found himself compelled to release records in a style he found more and more distasteful. As the decade progressed, he grew so disenchanted with the direction his career was taking that he began to preface concert appearances with the announcement that he would not be playing any of his disco hits. Finally in 1980, Atlantic and Mann went their separate ways, ending an almost twenty-year association.

In the 1980s, Mann entered something of a lean period. While he still toured and played clubs such as the Blue Note in New York City, his recording output, enormous in the prior two decades, withered away to virtually nothing and he disappeared from the position of public prominence he had enjoyed since the late Fifties. His fortunes rebounded in 1991, however, when he founded Kokopelli Records, a small independent jazz label of the sort with which he had always wanted to record. The company is based in Mann's hometown of Santa Fe, New Mexico. As of the mid-1990s, he was continuing to perform and record, while working full-time overseeing the production of jazz albums by such artists as David "Fathead" Newman and Jimmy Rowles. The release by Rhino Records in 1994 of an anthology of his recorded work, The Evolution of Mann, has brought the flutist some measure of the attention his work merits.

Herbie Mann's career does not lend itself to easy characterization. His most popular recordings, as critics were quick point out, were often imbued with a heavy commercial sound bordering on the formulaic. At the same time, though, his recorded work speaks volumes about his ability to merge widely-varying forms into a coherent and appealing style that was accessible to the average listener. Mann could also be described as one of the first "world" musicians; his sensitivity for non-Western musical forms, evidenced by his ability to integrate them into work that could be easily appreciated by a largely Western audience while still retaining the essential characteristics of its origin, has few parallels among the other musicians of his generation. In the final assessment, however, Mann's impact on jazz music does not need to be evoked in words; it can be heard issuing from clubs across North America and the world in musical form, the form that Herbie Mann created, a soaring flute solo floating above the low grind of the drums and the hum of the bass.

His last appearance was on May 3, 2003 at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival at age 73. He died at age 73 on July 1, 2003 after a long battle with prostate cancer.

Selective Works:

-Herbie Mann Plays, Bethlehem, 1955.

-Mann in the Morning, Prestige, 1956.

-The Magic Flute of Herbie Mann, Verve, 1957.

-Herbie Mann With the Wessel Ilcken Trio, Epic, 1958.

-Flautista: Herbie Mann Plays Afro-Cuban Jazz, Verve, 1959.

-The Common Ground, Atlantic, 1960.

-The Family of Mann, Atlantic, 1961.

-Sound of Mann, Verve, 1962.

-Herbie Mann at the Village Gate, Atlantic, 1962.

-Do the Bossa Nova With Herbie Mann, Atlantic, 1963.

-Herbie Mann Live at Newport, Atlantic, 1963.

-Nirvana, Atlantic, 1964.

-Latin Mann: Afro to Bossa to Blues, Columbia, 1965.

-My Kinda Groove, Atlantic, 1965.

-Standing Ovation at Newport, Atlantic, 1965.

-Herbie Mann and Joao Gilberto, Atlantic, 1966.

-Big Band Mann, Verve, 1966.

-Today, Atlantic, 1966.

-Our Mann Flute, Atlantic, 1966.

-The Herbie Mann String Album, Atlantic, 1967.

-The Beat Goes On, Atlantic, 1967.

-St. Thomas, Solid State, 1968.

-Memphis Underground, Atlantic, 1969.

-Muscle Shoals Nitty Gritty, Embryo, 1970.

-Push Push, Embryo, 1971.

-Turtle Bay, Atlantic, 1973.

-Et Tu Flute, MGM, 1973.

-London Underground, Atlantic, 1974.

-Discotheque, Atlantic, 1975.

-Bird in a Silver Cage, Atlantic, 1976.

-Gagaku & Beyond, Finnadar, 1976 Surprises, Atlantic, 1976.

-Super Mann, Atlantic, 1978.

-Mississippi Gambler, Atlantic, 1978.

-Brazil Once Again, Atlantic, 1978.

-Mellow, Atlantic, 1981.

-Astral Island, Atlantic, 1983.

-See Through Spirits, Atlantic, 1985.

-Glory of Love, A&M, 1986.

-Herbie Mann & Jasil Brazz, RBI, 1987.

-Opalescence, Gaia, 1989.

-Caminho de Casa, Chesky, 1990.

-Deep Pocket, Kokopelli, 1992 The Evolution of Mann: The Herbie Mann Anthology, Rhino, 1994.