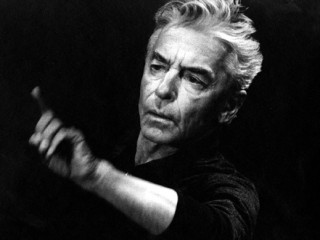

Herbert Von Karajan biography

Date of birth : 1908-04-05

Date of death : 1989-07-16

Birthplace : Salzburg, Austria

Nationality : Austrian

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2012-03-06

Credited as : Conductor, Berlin's Philharmonic conductor for 35 years, Herbert von Karajan Music Prize

0 votes so far

Herbert von Karajan is hailed by many as the greatest living conductor of orchestral music. He is revered for eliciting overpowering beauty and precision from the Berlin Philharmonic, the orchestra with which he had been most closely associated from the mid-1950s until poor health forced his retirement in 1989. Many critics have noted his emphasis is on the sound of perfection--of note-perfect expressions of sheer, pure beauty. His conducting method is one of total authority and power. Many associates have noted his seemingly unequaled obsession with music, one that renders him a dynamic dictator when it comes to realizing his ambitions with orchestras. Gustav Kuhn, who studied conducting under von Karajan, told biographer Robert Vaughan that the vaunted maestro is "the greatest, the last great one, the last of the period that started with [Hans] von Beulow in 1850." Kuhn added: "He is the exception. No one can do it like he can. He is so egocentric, so clever; he uses all of his immense power to do the things he wants."

He was born April 5, 1908, in Salzburg, Austria. He began studying piano in early childhood and first performed before the Salzburg public at age five. But teacher Bernhard Paumgartner found von Karajan too energetic and animated for the instrument and encouraged him to study conducting instead. In his mid-teens von Karajan saw the great maestro Arturo Toscanini and at that time vowed to conduct. But he also continued his piano studies, working under celebrated musician Josef Hofmann. von Karajan later studied under another acclaimed artist, conductor Clemens Krauss, while attending Vienna's Academy for Music and the Performing Arts. Aside from his musical pursuits, von Karajan also studied philosophy at the University of Vienna.

In late 1928, von Karajan made his first conducting appearance by leading the student orchestra at the Academy. Soon afterwards, he arranged his own professional audition by hiring an orchestra. Attending that performance was the director of the Ulm Opera House, whose conductor, von Karajan had learned, was ill. In early 1929, von Karajan was hired as a late replacement conductor for a performance of Mozart's opera The Marriage of Figaro. von Karajan then obtained the Ulm post and began developing the performances there. Aside from his strictly musical duties, he supervised technical aspects, such as lighting and staging as well. When the company was between seasons, von Karajan often returned to Salzburg to assist conductors such as Toscanini and composer Richard Strauss. Eventually, he led courses for other conductors at the Salzburg Festivals.

By the early 1930s, von Karajan's career was prospering, and he was enjoying increasing recognition as an impressive, multi-talented musician. The decade, however, was not entirely one that von Karajan recalls fondly. In 1935 he was named general music director of the Aachen Opera House. He has since claimed that for professional reasons he joined the Nazi Party at the time of the Aachen appointment. Nazi records, though, disclose that von Karajan had actually joined the party two years earlier, in 1933, within three months of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler's assumption of power in Germany. von Karajan's actual association with the Nazis remains unclear, and many observers consider it likely that he made a professional, as opposed to a political, move to join the party.

The 1930s also marked the beginning of von Karajan's supposed feud with conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler, whose stature in Germany was such that he remained prominent despite his refusal to join the Nazi Party. As a result of his disdain for the Nazis, though, Furtwangler left his position as director of the Berlin State Opera. By that time, von Karajan had already sparked great public interest in Berlin as a result of his stunning interpretation of Richard Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde. When he returned there in 1938, he gained further enthusiasm with his rendition of Mozart's The Magic Flute. The acclaim, however, did not impress Furtwangler, who was apparently disgusted by von Karajan's seeming compliance with the Nazis. Furtwangler used his influence with Nazi culture minister Josef Goebbels to prevent von Karajan from conducting the Berlin Philharmonic.

von Karajan nonetheless enjoyed great prominence in Berlin through his work with the Berlin State Opera, where he had replaced Furtwangler in 1938. But the acclaim and hectic pace were hardly conducive to von Karajan's art. "It was a dangerous time in my life," he later told biographer Vaughan. "Things were going so fast, I was having so much success that I was always apprehensive. Because wherever I went it was a sensation, people said it has never been like this. First, this put other conductors in opposition to me. Second, the expectations were at a level that one could not hope to fulfill.... And people began to say that I was a fast-burning candle, that I would soon burn out."

von Karajan turned to yoga, and later to Zen, to stabilize himself. But his personal and professional activities, remained cause for anxiety. In 1942 von Karajan violated Nazi dictum by marrying a woman of Jewish ancestry. As a result he was dismissed from the party. He nonetheless continued to conduct in Berlin during World War II, constantly rescheduling concerts as bombings began to destroy the city. von Karajan's activities during this period are obscured by his own privacy and lack of records. He apparently fled to Italy with his wife in 1944 and remained there until the war ended.

Following World War II, von Karajan underwent de-Nazification. For more than a year he was refused classification as a conductor by the Occupation government. In early 1946, however, he led the Vienna Philharmonic in concert. Record executive Walter Legge was awed by von Karajan's performance. In soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf's book On and Off the Record, Legge wrote: "I was absolutely astonished at what the fellow could do. The enormous energy and vitality he had were hair-raising."

Through Legge, von Karajan was able to record for a Viennese concert society, the Gessellscaft der Musikfreunde, of which he was eventually named artistic director for life. In 1947, von Karajan finally obtained de-Nazification status and resumed conducting in public, whereupon the Vienna Musikfreunde hired him for a series that evolved into an annual event. The following year, he obtained an important post: music director and conductor at La Scala, the renouned opera house in Milan, Italy. At La Scala, where von Karajan remained until 1955, he enjoyed great success with such artists as soprano Maria Callas. He received further acclaim with his productions of Wagner's Tristan un Isolde, Die Meistersinger von Nurmberg, and the entire Ring of the Nibulungen cycle at Byreuth, West Germany, where festivals are devoted exclusively to Wagner's operas.

von Karajan continued his return to prominence in the early 1950s through tours with the Philharmonia Orchestra and the Vienna Philharmonic. Perhaps the turning point in his career came in 1955 when Furtwangler died prior to a tour of America with his orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic. von Karajan agreed to tour with the orchestra on the condition that he be named conductor for life. Upon obtaining such an agreement, von Karajan led the Berlin Philharmonic on the tour, which proved enormously successful. The following year he was named artistic director of the Salzburg Festival, from which Furtwangler had long succeeded in keeping him. Then he also became artistic director of the Vienna State Opera, where he had led a much praised production of Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor featuring Maria Callas.

By the end of the 1950s, von Karajan was known as much for his whirlwind schedule as for his musical prowess. And as if the pace of his concertizing were not exhaustive enough, he began recording extensively, producing highly prized interpretations of works by Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Brahms, and Richard Strauss. Throughout the 1960s he continued to record constantly, repeating and even re-repeating portions of his burgeoning catalog. The records contributed greatly to his status as an unrivaled conductor--and to the Berlin Philharmonic's claim to the title of the world's greatest orchestra. Of course, von Karajan and the Philharmonic continued to triumph with their live performances. Particularly impressive were their four successive productions of Wagner's Ring cycle at the Salzburg Easter Festival, which von Karajan commenced in 1967.

In recent years, von Karajan sustained his reputation as one of the world's greatest--if not the greatest--of conductors. Artists such as soprano Leontyne Price and fellow conductor Seiji Ozawa are quick to offer their reverential praise, and many newcoming musicians cite him as a generous influence. von Karajan recorded extensively--his canon now exceeds three hundred recordings, including five complete cycles of Beethoven's nine symphonies. In addition, he appeared on numerous radio and television broadcasts and was filmed many times. Among his many triumphs in the 1980s was a Salzburg Festival production of Mozart's Don Giovanni featuring soprano Kathleen Battle and baritone Samuel Ramey.

Health was the only obstacle to von Karajan's continued domination in classical music. He suffered a stroke in 1978 and was left partially paralyzed following emergency surgery in 1983. His health continued to worsen, and in April 1989 von Karajan announced his retirement from the Berlin Philharmonic after nearly 35 years as its conductor.

Karajan officially retired from conducting the Berlin Philharmonic, but at his death was conducting a series of rehearsals for the annual Salzburg Music Festival. He died of a heart attack in his home on July 16, 1989 at the age of 81.

Karajan was the recipient of multiple honours and awards. In 1977 he was awarded the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize. On 21 June 1978 he received the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Music from Oxford University. He was honored by the "Médaille de Vermeil" in Paris, the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society in London, the Olympia Award of the Onassis Foundation in Athens and the UNESCO International Music Prize. He received two Gramophone Awards for recordings of Mahler's Ninth Symphony and the complete Parsifal recordings in 1981.

He received the Eduard Rhein Ring of Honor from the German Eduard Rhein Foundation in 1984. In 2002, the Herbert von Karajan Music Prize was founded in his honour; in 2003 Anne-Sophie Mutter, who had made her debut with Karajan in 1977, became the first recipient of this award.