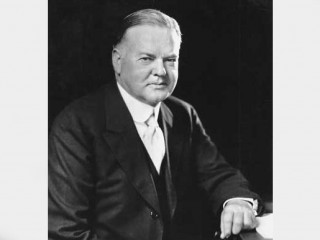

Herbert Hoover biography

Date of birth : 1874-08-10

Date of death : 1964-10-20

Birthplace : West Branch, Iowa, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-10-06

Credited as : Politician, former U.S President,

2 votes so far

President of the U.S., who, though castigated by contemporaries for having caused and exacerbated the Great Depression, was the first president to use the power of the federal government to attempt to assuage its effects.

* 1895 Graduated Stanford University

* 1897 Joined Bewick, Moreing as mining engineer

* 1897--1914 Worked in Asia, Africa, and Europe

* 1914--15 Served as chairman of the American Relief Committee

* 1915--1917 Named chairman of the Commission for Relief in Belgium

* 1917--19 Appointed U.S. Food Commissioner

* 1919 Served as chairman of the Supreme Economic Conference

* 1919--20 Appointed chairman of the American Relief Administration

* 1921--28 Named secretary of commerce

* 1929--33 Elected president of the United States

* 1929 Onset of the Great Depression

* 1932 Defeated for re-election by Franklin D. Roosevelt

* 1947--55 Appointed chairman of Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch

* 1964 Died in New York

Born on August 10, 1874, in West Branch, Iowa; son of Jesse Clark (a blacksmith) and Hulda Randall Hoover (a teacher); died on October 20, 1964, in New York, N.Y.; married: Lou Henry, February 10, 1899; children: Herbert Clark Hoover, Allan Henry Hoover.

Herbert Hoover was born in a farming community inhabited by Quakers. His father died when the boy was six years old; his mother died three years later. After living a year with an uncle, he was dispatched to another uncle in Newberg, Oregon, where he attended local Quaker schools. In 1891, he enrolled in the first class at what was then known as Leland Stanford Junior University and graduated four years later with a degree in mining engineering.

After working for a while for the U.S. Geological Survey and marrying fellow student Lou Henry, Hoover was hired by the prestigious British firm of Bewick, Moreing to take charge of a mining project in the Australian gold fields. During the next few years, he would travel to Indochina, Russia, Africa, Europe, and Asia, usually in command of teams hired to open, operate, or renovate mines.

By 1914, the 40-year-old Hoover was a retired multimillionaire with homes in London, New York, and Stanford, who concerned himself with charitable activities. In London at the outbreak of World War I, Hoover helped repatriate American tourists and others who wanted to return home. As a result of this experience, he was asked to take charge of a new body organized to provide relief to the Belgians. He accepted, with the understanding from both sides that he might travel freely on the Continent. He achieved international recognition for his humanitarian efforts.

Hoover Coordinates Food Supplies in World War I

When the United States entered the war in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Hoover to become Food Administrator, coordinating the procurement and supply of foodstuffs to the Allies and conservation efforts at home. After the war, Hoover attended the Versailles Conference that drew up the peace treaty with Germany and its allies, impressing all with his knowledge and abilities. John Maynard Keynes, the famous economist who served an the British delegation, later wrote: "Mr. Hoover was the only man who emerged from the ordeal of Paris with an enhanced reputation."

Delegations from both American political parties visited Hoover and requested that he place his name in consideration for the 1920 presidential nomination. Several of Wilson's Democratic advisors hoped for a ticket headed by Hoover with Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt in the second slot. As it happened, Hoover was a Republican, and in any case not interested in campaigning for either party's nomination. The Republicans selected Warren Harding, with Calvin Coolidge chosen for the vice presidency. When Harding won the election, he invited Hoover to enter his cabinet as secretary of commerce and Hoover accepted. He remained in that position after Coolidge became president in 1923 on Harding's death.

One of his predecessors told Hoover his would be an easy job. All it required was making certain the fish went to bed and the lighthouses were turned on at night. This was an exaggeration, of course, but in the past there had been few active commerce secretaries. Hoover changed this. He was a whirlwind of activity, prompting one reporter to remark that he was secretary of commerce and undersecretary of just about everything else.

Hoover had developed a philosophy of government-business-labor relations he labeled "associationalism." He asked for an end of business-labor strife and a reconsideration of the government's attitude toward both. In place of intense competition and conflict, he called for cooperation. Government would encourage industry associations to prod companies to cooperate, while labor would be rewarded for working with management to increase efficiencies and make innovations.

"The total interdependence of all industries compels trade associations in the long run to go parallel to the general economic good," he said. "I believe that through these forces we are slowly moving toward some sort of industrial democracy. . . . With these private collective agencies used as the machinery for the elimination of abuses and the cultivation of high standards, I am convinced that we shall have entered a great new era of self-governing industry."

Hoover was a strong believer in individualism, as expressed in his book American Individualism. He feared the might of the state and hoped the American people would not ask too much of government, for together with the power to bestow benefits was the power to withhold them. Hoover, who considered himself a Jeffersonian, felt that citizens should be self-reliant and independent.

Among Hoover's accomplishments at the Commerce Department was the creation of the Federal Radio Commission, which eventually became the Federal Communications Commission. More than anyone else, he designed the broadcasting industry. Hoover was also responsible for the introduction of the Air Commerce Act of 1926 which instituted the Bureau of Air Commerce. This body helped establish air routes, set up safety regulations, encouraged the construction of airports, and assisted in the development of airlines.

In 1921, Hoover served as chairman of the President's Conference on Unemployment, leading a group of experts in planning for governmental policy in case of an economic downturn. This was a controversial notion since no administration had ever assumed such responsibilities. In 1928, Hoover was named chairman of the Committee on Economic Changes. The report of the committee called for government spending on public works to alleviate hard times, a concept he endorsed.

He Is Elected President

That year, 1928, the Republicans nominated Hoover for the presidency and Senator Charles Curtis of Kansas for the vice presidency, while the Democrats selected a ticket of Governor Al Smith of New York and Senator Joseph Robinson of Arkansas. Hoover won with an electoral vote of 444 to 87, with 21.5 million popular votes against Smith's 15 million. Then and afterward it would be asserted that Smith lost because of his Catholic religion. While some may have voted against Smith for this reason, there is strong evidence that still more voted for him because of his religion. Hoover won, at least in part, because the nation was prosperous and at peace, and the man who was known as "The Great Engineer" was the most popular political figure in the land.

Hoover took the oath of office an March 4, 1929. "I have no fears for the future of our country," he said in his Inaugural Address. "It is bright with hope." Calling Congress immediately into session to consider farm relief, tariff reform, and to weigh the creation of a National Commission on Law and Enforcement to investigate Prohibition, Hoover indicated his intention to be an activist chief executive. He asked Congress to provide federal assistance in the marketing of agricultural products and to raise the tariff to protect farmers. The Agricultural Marketing Act of 1929 created the Federal Farm Board, which had a revolving fund of $500 million to be loaned to farm cooperatives to assist in marketing. Though Hoover did not get his tariff changes, he vowed to return to the problem the following year.

The economy had performed admirably during the 1920s. After a sharp postwar recession in 1921, during which the Gross National Product (GNP) fell from $91.5 billion to $69.6 billion, business improved. Except for a brief recession in 1927, most parts of the nation and most industries experienced good times. In 1929, the GNP came in at $103.1 billion.

Prices at the nation's securities markets soared, even more sharply than the GNP, with the Dow-Jones Industrial Average, the most popular measure of stock prices, rising from a low of 64 in 1921 to 381 in September 1929. According to one estimate, there were 2.4 million shareholders in 1924; this figure rose to between 4 and 7 million by 1929. Fewer than 4% of Americans owned stock, high by earlier standards but hardly a sign that the entire nation was in the midst of wild speculation. The Federal Reserve Board, which had some responsibility for the stock markets, cautioned against speculation in early 1929, as had both Presidents Coolidge and Hoover. Ultimately a number of factors including speculation, worldwide overproduction, and debt led to economic vulnerability in both Europe and America. Finally, on October 24, 1929---known as Black Thursday---the Crash began. Five days later on October 29, a worse plunge in the market began the downward slide that did not level off until 1932.

Shortly after the Crash, Hoover said, "The fundamental business of the country---that is, the production and distribution of goods and services---is on a sound and prosperous basis." He did act to alleviate misery, the first time any American president had done so in a depression. Hoover urged the Federal Reserve to make it easier for businesses to borrow, while the Farm Board helped stabilize food prices. Hoover also convened conferences of business and labor leaders, who pledged to maintain employment and wages.

Domestic Programs Fail To Help Economy

In an attempt to help protect American industries, Hoover recommended tariff changes, and the conservative Republicans in Congress responded with the Hawley-Smoot Tariff, which raised rates substantially. With some reluctance Hoover signed the measure, which, as it turned out, sparked a trade war. American exports declined, and most economic historians believe the tariff helped deepen the depression.

By the winter of 1930, it seemed evident that these policies either were wrong or insufficient. In October, Hoover appointed an Emergency Committee for Employment, which recommended a federal public works program. Still a believer in individualism and fearful of such direct intervention in the economy, he rejected the notion. In December, however, at Hoover's suggestion, Congress appropriated $125 million to expand operations of the Federal Land Banks and established a system of home-loan banks capitalized at $125 million. The following year, when most of Europe experienced financial panics and economic decline, Hoover made a futile call for international cooperation to stimulate national economies.

The capstone of the Hoover program was the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, capitalized at $500 million with the authority to borrow another $1.5 billion. This money was to be loaned to and invested in banks and insurance companies to keep them solvent. But this too, like so much of the Hoover program, proved inadequate.

By 1931, some advisors suggested Hoover ask Congress to provide direct aid for the unemployed and those who had lost their homes. Fearing the American people would lose their love of freedom if government provided such services, he refused to do so, calling instead for additional assistance from philanthropic organizations and churches.

In the area of foreign policy, Hoover proved more of an internationalist than the American public. When Japanese militarists invaded the Chinese province of Manchuria in 1932, Hoover responded with the Stimson Doctrine (named after Secretary of State Henry Stimson), in which he declared the United States would not recognize any change that would impair China's sovereignty. While the U.S. was not a member of the League of Nations, a League commission condemned the aggression.

In the summer of 1932, with the unemployment rate standing at 23%, the Republicans renominated Hoover and Curtis, while the Democrats nominated Franklin D. Roosevelt and Speaker of the House John Nance Garner of Texas. Roosevelt won in a landslide, with 471 electoral votes to Hoover's 59, and 22.8 million popular votes to 15.7 million.

Bitter over this repudiation, Hoover left office and for a while all but disappeared. While there was recovery under Roosevelt's New Deal, by 1936 the unemployment rate was still 17%, prompting Hoover to seek support for a run against Roosevelt. Finding none, he abandoned all hope of a return to politics. He wrote his memoirs, contributed occasional articles to magazines and newspapers, and spoke before Republican audiences, all the while criticizing Roosevelt for being a socialist who was out to destroy free enterprise and individualism. Later, alluding to the 17% unemployment rate in 1939, Hoover would remark that while it was true he could not bring the nation out of depression for the three years he had remaining in office, Roosevelt had failed to do so in more than seven years. Economic activity attendant with the outbreak of World War II, not the New Deal, finally brought an end to the Depression.

When war erupted in Europe in 1939, there was some thought of using Hoover's talents in relief efforts, but Roosevelt refused to consider him. In fact, Hoover did not set foot in the White House from the time he left until 1947, when President Truman asked him to lead the Commission on the Organization of the Executive Branch. This work extended into the Eisenhower Administration.

Gradually Hoover returned to the public eye, and at Party conventions he supported conservative candidates and policies. Active almost to the end of his life, Hoover died in 1964, at the age of 90.