Henry McNeal Turner biography

Date of birth : 1834-02-01

Date of death : 1915-05-08

Birthplace : Abbeville, South Carolina, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2010-06-04

Credited as : African-American leader, African Methodist Episcopal Church,

1 votes so far

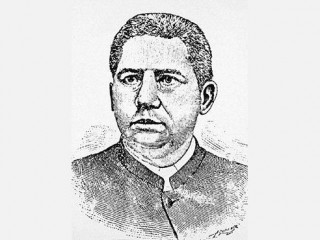

Henry McNeal Turner (1834-1915), African American leader and a bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, argued for African American emigration to Africa.

Turner was born free in Newberry Court House, South Carolina, on February 1, 1834, to Hardy and Sarah Turner (d. 1888). His father was the son of Julia Turner, a white plantation owner, and her black superintendent. His maternal grandmother, Hannah Greer, told her grandson that her husband, David Greer (d. 1819), was the son of an African king, enslaved but then set free because of his royal birth. Hardy Turner died while his son was a child. Henry McNeal had a sister who died young and two more half-siblings from his mother's marriage to Jabez Story.

Under state law Turner was apprenticed out several times as a boy. He worked in the cotton fields alongside slaves but vigorously resisted whippings, a punishment to which free blacks were not legally subject. He disliked his apprenticeships to a blacksmith and a carriage maker and ran away at least once. When Sarah Turner married Jabez Story around 1848, she and her son moved to join him in Abbeville. Turner was hired to do janitorial work in a lawyers' office when he was 15 and by his 20s was a beginning carpenter.

Although Turner's mother made efforts for him to be taught to read earlier, his education dates from his job at the law office in Abbeville about 1819. In direct violation of state law, they instructed him in elementary subjects except for English grammar. Converted to Christianity on June 12, 1844, and joining the Baptist church, Turner's mother influenced him spiritually. He was also stirred by Methodist preachers at summer camp meetings near Abbeville between 1848 and 1851 and admitted to the Methodist Church in 1848. As documented by Angell, Turner described his conversion experience, "I fell upon the ground, rolled in the dirt, foamed at the mouth and agonized under conviction until Christ relieved me by his atoning blood."

In 1851 Turner was licensed as an exhorter and in 1853 as a preacher. In December of 1854 he acquired a guardianship certificate after naming a white man to vouch for his good behavior and he could travel as an evangelist. The splits between Northern and Southern Baptists and Methodists had the effect of easing Southern fears of separate black churches after the 1840s, and supervision of the religious activities of blacks became more relaxed, except in South Carolina due to the experience of the Denmark Vesey conspiracy of 1822. Turner thus found semi-independent black urban churches in the South, especially in Georgia, which he soon came to prefer. From 1853 to 1858 Turner preached throughout the South, visiting South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. A spell-binding speaker, he attracted both blacks and whites to his sermons.

On August 31, 1856, he married Eliza Ann Peacher, aged 19 and the daughter of a leading house builder in Columbia, South Carolina. The marriage between Turner and his first wife produced 14 children before her death in 1889. Only four lived to adulthood, and only two survived their father: John Payne (b. March 1, 1859) and David Milchon, sometimes called McNeal by his father (b. October 31, 1860). His daughter Victoria died in childbirth in 1892, and daughter Josephine died after an operation for an internal tumor in 1897.

In 1893 Turner married Martha DeWitt of Bristol, Pennsylvania. She died in early 1897. In 1900 he married Harriet Wayman, the widow of a fellow AME bishop. She died by 1907. On December 3, 1907, Turner married Laura Pearl Lemon, a divorced woman, in the face of considerable opposition from the Council of Bishops and his own grand-daughter Charlotte Lankford. Born about 1880 Laura Pearl Lemon had been hired as Turner's assistant secretary in June of 1897 and became chief secretary in 1900. She also became an assistant editor of The Voice of the People, Turner's newspaper, head of the missionary department of Morris Brown College, and president of the Women's Home and Foreign Missionary Society of Northern Georgia. Turner's fourth wife died at the age of 35, about five months after his death in 1915. He had no children from his final three marriages.

Turner had an extremely patriarchal view of marriage. Ponton explained, "as a husband he made provision for every enjoyment and comfort for the woman he selected as the partner in life, so that no complaint could come to him from her to retard him in his God-given work. ... His will was the supreme law and the controlling influence of his home."

Joins AME

In New Orleans in 1857 Turner met Willis H. Revels, pastor of St. James Church, who told him of Richard Allen and the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Turner made no immediate attempt to join, and it has been suggested that during this time he was still working out the freedom of his wife, who was probably a slave. He spent the next year continuing to work for the Southern Methodists. In particular he did outstanding work alongside three white Methodist ministers in a revival in Athens, Georgia, in April and May of 1858, where Turner claimed 100 converts. At the revival, marked by a quiet intensity of prayer unlike the emotionalism of Turner's own conversion, he preached by invitation to the white students and professors of the University of Georgia.

Around summer's end Turner traveled with his wife to St. Louis to join the AME church at its annual conference in August of 1858. Although his desire to join an all-black church was genuine, it may not have been the only motive for the move. The Turners were part of a wider emigration of free blacks from the South just before the Civil War.

Turner's rise within the denomination was rapid. From 1858 to 1860, he pastored two small churches in the Baltimore conference and endeavored to supplement his education. Then he led Union Bethel in Baltimore from 1860 to 1862 and Israel Church in Washington, D.C., from 1862 to 1863. He was ordained deacon in April of 1860 and elder in 1862. He continued to build an outstanding reputation in the church through his work in the AME Book Concern, his selling and writing for the Christian Recorder, and his participation on the conference's Committee of Missions. In Washington he joined the Prince Hall masons and cultivated white politicians like Charles Sumner as he carried out extensive renovations on the church building. He displayed a rigidity and refusal to back down even in the face of majority opposition in his conduct of quarterly meetings of local AME ministers. His diaries show that a real anxiety about the possibility of damnation underlay his outer show of confidence, and he retained his belief in the literal existence of Hell until the end of his life.

Turner came to the conclusion that black troops should fight for the Union by the end of 1862. When the Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863, Turner joined other blacks to recruit soldiers. The First Regiment of the United States Colored Troops came into being by summer, and Turner applied to become its chaplain. William Hunter, an AME minister from Baltimore, also had turned in an application for a position as chaplain. Hunter entered the army on October 10, 1863, and Turner received his commission on November 6.

Turner suffered a series of illnesses during the first few months he was in the army, culminating in a severe attack of smallpox in February of 1864. After fighting in Virginia, his regiment was part of the forces which captured Fort Fisher, North Carolina, in January of 1865.

Turner was thus positioned to join in the competition between the AME and the AME Zion churches for the allegiance of blacks in North Carolina. (AME Zion mostly prevailed in North Carolina.) In Georgia in December of 1865 Turner took on organizing his church, continuing efforts which had begun a year earlier but which were faltering because of the death of one prominent missionary and the departure of the other. Turner decided to resign his commission and soon afterwards left the Freedmen's Bureau. Until 1871 Turner devoted tremendous energy to the organization and development of the AME Church in Georgia. He became church superintendent of the state from 1866 to 1871. Akin to the position of bishop, his job involved almost constant travel and preaching. For a while, there was limited cooperation with the ME Church South: both denominations were eager to forestall the activities of the ME Church North in the state. The ME Church South agreed that its black congregations could leave to join the AME Church but retained control of church properties. The adherence of established congregations to the AME and a vigorous revival movement among all denominations black and white in 1866 brought in many new members. Soon this growth revealed the problem of the low supply of experienced and literate black ministers. Turner met this need by waiving the requirements for literacy and even for a thorough knowledge of the Bible. He appointed many temporary preachers, presenting the successful among them to the Annual Conference for Ordination.

Enters Politics

In addition to carrying out his heavy work load as a minister, Turner became heavily involved in Reconstruction politics from 1867 to 1871. His disappointments in the political sphere intensified his distrust of whites and convinced him later that separation of the races and black emigration could be the only hope for black empowerment. He threw the resources of his church into organizing the Republican Party in Georgia. Thirty-six blacks, including six AME ministers, were elected to the state constitutional convention, which met from December of 1867 to March of 1868.

Striving to improve relations with whites, Turner pursued a conciliatory conservative policy during the convention. He even favored a full pardon for Jefferson Davis and voted against inserting in the constitution a provision that blacks could hold office. However, his politics did little to attract white allies and stimulated hostility from all sides. Nevertheless, Turner won election to the subsequent legislature, and the failure of conciliation became increasingly evident. The legislature voted to expel black members by an 83 to 23 vote with black members forbidden to vote on the issue. Turner rose to denounce the decision in a three-hour speech on September 3, 1868.

It was now clear that any political power for blacks in Georgia rested on support at the national level, and that state support disappeared with the end of Reconstruction in Georgia in 1871. Klu Klux Klan terror tactics and Democratic Party efforts to deny the ballot to blacks combined with the factional infighting in the Republican Party contributed to the demise of political power for blacks.

In the legislative elections of 1870, Turner appeared to have won election to the legislature by 17 votes, but his margin of victory disappeared in a fraudulent recount. He would subsequently serve a while longer in a legislative session held under military guard to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment.

In Macon, Georgia, his position was undermined by a virulent quarrel with Republican J. C. Swayze, editor of the Macon American Union. Swayze and Turner had been reluctant allies, but they eventually broke when Turner was appointed postmaster in Macon in May of 1869, and the entire staff of the post office walked off the job. As the controversy swirled, Turner was seen in Macon in July, in the company of Marian Harris, a prostitute whom he had known since 1867 and with whom he had been seen in Atlanta, Philadelphia, and Washington. She was carrying $1,800 in phoney Bank of New Jersey notes and was arrested. Turner was then accused of conspiring with her to pass counterfeit money. After a three-day hearing the charges against him were dismissed. Swayze published more allegations about financial improbity of Turner and privately circulated some of Turner's correspondence containing obscenities. Turner was forced to resign from his government position. The white community soon forgot about him and the scandal, but the allegations of infidelities with Harris and other women undermined his position among some blacks.

Turner's political involvement brought trouble to the church. The ME Church South--predominantly white-controlled--no longer cooperated with the AME and supported the formation of the Colored [now Christian] Methodist Episcopal Church in January of 1869. The ME Church South used its control of titles to church property as a lever. The rate of growth in the AME Church dropped from 5,000 to 500 new members a year. On the positive side the AME Church became completely independent and viewed much more favorably by black Baptists.

In 1872 Turner became pastor of St. Philip's in Savannah, a post he held for the four years. He was responsible for the completion of a new church building. He was also involved in local life, delivering and publishing several lectures, and active as a Mason. He completed a new hymnal, published in 1876, and a church standard through the 1890s. He continued to be active in the conference without completely abandoning politics. While his position of inspector in the U.S. Custom House excited little animosity, he was unsuccessful in an attempt to be elected coroner.

Becomes an Emigrationist

As conditions for blacks in the South worsened, Turner was also beginning to take a pro-emigration position. At first he did not focus exclusively on Africa, but the desire to Christianize the continent finally led him to select it as a destination for American blacks. By 1873 his pronouncements in favor of emigration were emphatic enough to be challenged by Northern blacks like Frederick Douglass, and Turner began to move closer to the American Colonization Society. In 1876 he became a lifetime honorary vice-president of that organization, whose formation in 1816 had sparked the first national black protest movement.

In that year, too, Turner won election to head the AME publishing concern, based in Philadelphia, which was in difficult financial straits. Turner gave the concern high visibility, but his hectoring of ministers who did not subscribe to the Christian Recorder and his extensive absences traveling did not relieve the financial pressures. After a sheriff's seizure of the concern's property in February of 1878, Theodore Gould was brought in as deputy, and together he and Turner did much to stabilize the operation. In his travels Turner became increasingly attuned to the problems of black farmers, especially the practice of debt peonage. He supported emigration to Liberia on the ship Azor in 1878. The efforts of mass black migration to Kansas, culminating in the spring of 1878, also received Turner's blessing.

Turner was one of the candidates of Southern members of the AME for election as bishop in the General Conference of 1880. Since Daniel A. Payne, the best known and most respected bishop, believed the allegations about Turner's sexual and financial irregularities, he was firmly against Turner's election. AME Southerners prevented the charges against Turner from being heard on the convention floor and elected their candidates. Having carried the election of their candidates and securing regional representation in the national leadership, the Southern blacks could now split among contending factions. In order to avoid an open quarrel that might have damaged the church, Payne consecrated Turner bishop, and the two buried their public differences. Turner was the proposer of the celebration of Payne's thirtieth anniversary as a bishop in August of 1882. Although there would be disagreements among the men over the following years, Payne presided at Turner's 1893 marriage to Martha DeWitt just a few months before his death in November.

As a bishop Turner presided over various districts for terms of four years. He established his home in Atlanta. While his rough comments on ideological opponents might suggest that he would run into difficulties, Turner was a successful bishop, skilled at managing his ministers and even called in to resolve disputes in other episcopal districts. To offer guidance in ecclesiastical disciplinary matters, he published The Genius and Theory of Methodist Polity in 1885.

Concerned with what he perceived as a decline of piety, Turner favored the return of revival meetings. While he did not approve of shouting in regular church services, he did wish to continue the emotionalism of the camp meetings of his youth. In 1895 he became senior bishop of the denomination as a result of the death of older bishops and, in 1896, returned as bishop of Georgia. Turner became chair of the Morris Brown Board of Trustees from 1896 to 1908, but his efforts for industrial education were unsuccessful. As a respected, but controversial elder, he was perceived as conservative by the rising generation of ministers. One of Turner's forward-looking initiatives, however, was overturned by the church in 1887: his 1885 ordination of a woman, Sarah Ann Hughes of North Carolina.

Turner maintained that doctrinal differences strengthened a church and he gradually came to a liberal position on the Bible, holding that not all parts are equally inspired. In 1895 he stated that a new translation of the Bible by and for blacks was needed. Thus he initiated some of the themes of black theology. Aroused by the implicit racism in the religious language of whites, Turner declared, as cited by Angell, "The devil is white and never was black." In 1895 he told a black Baptist convention in Atlanta, "God is a Negro." Angell quoted his defense of this statement in the Voice of Missions:

We have as much right biblically and otherwise to believe that God is a negro, as you buckra or white people have to believe that God is a fine looking, symmetrical, and ornamented white man. ... Yet we are not stickler as to God's color, any way, but if He has any we would prefer to believe that it is nearer symbolized in the blue sky above us and the blue water of the seas...but we certainly protest against God being a white man or against God being white at all.

Turner's attempts to build racial pride rested on his conviction that the first humans were black. An unfortunate counterpart of his high estimation of blacks was the fierceness of his denunciations of those who did not live up to his ideals. This intransigence made him many enemies.

Fosters African Missions

Turner also pushed for increased missionary activity in Africa as opportunities opened up there. Turner gave concrete expression to his evangelization hopes when he made his first trip to Liberia, where he received an enthusiastic reception, in late 1891. To support the mission work, he organized a new women's auxiliary, the Woman's Home and Foreign Missionary Society, to abet the efforts of an older, mostly Northern Women's Parent Mite Missionary Society. Between 1892 and 1900 Turner organized missionary societies in 11 annual conferences. Two of his wives, Martha DeWitt Turner and Laura Lemmon Turner, were very active in the organizations. He continued to speak in favor of emigration to Africa at a convention he organized in Indianapolis in 1893. However, he faced opposition from the majority of those in attendance.

In Liberia Turner's missionary efforts were weakened by the personality defects of Alfred L. Ridgel in Liberia (Ridgel probably committed suicide in September of 1896 by leaping off a river boat). Turner also quarreled with the Sierra Leone missionary John R. Frederick, who in 1897 left the AME church in disgust, taking his congregation with him. Although the AME church survived in these countries, Turner personally became very unpopular.

New possibilities opened in South Africa, where the independent Ethiopian Church, founded by Africans, sought to unite with the AME in 1896. By the time Turner visited Africa in 1898, many Africans were almost ready to consider him a Messiah. He took vigorous steps to organize the AME Church there. As he had earlier in Georgia, he ordained ministers with little regard to their education. He also took the controversial step of naming African James D. Dwane as vicar bishop, a sort of missionary bishop, subject to later approval by the church. The action and Dwane's character were attacked although Turner's action was sustained. However, Dwane broke with the AME and sought admission to the Anglican Church taking along several ministers just as the Boer War broke out in late 1899. The AME finally agreed to appoint missionary bishops to work in South Africa in 1900, naming Levi Jenkins Coppin and Marcellus Moore.

Turner's position on emigration was becoming increasingly unpopular, especially when the white-owned International Migration Society took two shiploads totaling more than 500 blacks to Liberia in 1895 and 1896. The airing of the complaints of emigrants and returnees contributed to the unfavorableness of emigration. Turner ceased coupling emigration and missionary work in the later part of the decade.

Other events further injured Turner's career. In 1900 Robert Charles of New Orleans, who was an agent for the paper Turner edited for the AME, the Voice of Missions, killed several policemen before being captured and lynched. Turner was forced to give up the paper as a result, but promptly launched his Voice of the People as a replacement. When he tried to raise money to buy ships to carry emigrants to Africa in 1903, the attempt was a dismal failure with no more than $1,000 raised.

As the tide of antiblack violence and lynching rose, in 1897 Turner caused a stir when he advocated that every black man in the United States keep several guns in the house. In 1906 his disgust with America led to his famous statement about the flag, which was reprinted by Angell, "to the Negro in the country, the American flag is a dirty and contemptible rag. Not a star in it can the colored man claim, for it is no longer the symbol of our manhood rights and liberty."

In 1899 Turner suffered a mild stroke from which he seemed to have completely recovered. Still he became increasingly fragile after the turn of the century although he continued to work diligently. Despite the controversy caused by his fourth marriage in 1907, his new wife's care and protection aided in prolonging his life. He was not given a district to supervise in 1908, but was appointed church historiographer. However, he did little in this position. In 1912 he was named to supervise Michigan and Canada. On his way to a church conference in Ontario, he collapsed from a massive stroke on the ferry to Windsor, Ontario, on the early morning of May 8, 1915, and died a few hours later. It is estimated that 25,000 persons viewed his remains in Atlanta before the funeral ceremony on May 19. He was buried in South View Cemetery.

Turner inspired controversy for his support of emigration to Africa but also gained much respect for his vigorous and effective leadership in his church. He focused on the problems of poor Southern blacks in a way than many of his contemporaries did not, and themes that he first articulated have present-day relevance in black theology.