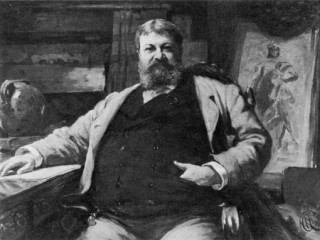

Henry Hobson Richardson biography

Date of birth : 1838-09-29

Date of death : 1886-04-27

Birthplace : St. James Parish Louisiana, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Arhitecture and Engineering

Last modified : 2012-01-23

Credited as : architect, Richardsonian Romanesque style, one of the recognized trinity of American architecture

1 votes so far

Richardson went on to study at Harvard College and Tulane University. Initially, he was interested in civil engineering, but shifted to architecture, which led him to go to Paris in 1860 to attend the famed École des Beaux Arts in the atelier of Louis-Jules André. He was only the second U.S. citizen to attend the École's architectural division, — Richard Morris Hunt was the first - and the school was to play an increasingly important role in training Americans in the following decades.

He didn't finish his training there, as family backing failed due to the U.S. Civil War.

Richardson returned to the U.S. in 1865. The style that Richardson developed over time, however, was not the more classical style of the École, but a more medieval-inspired style, influenced by William Morris, John Ruskin and others. Richardson developed a unique and highly personal idiom, adapting in particular the Romanesque of southern France. His early works, however, were not very remarkable. "There are few hints in the mediocre work of Richardson's early years of what was to come in his maturity, when, beginning with his competition-winning design... for the Brattle Square Church in Boston, he adopted the Romanesque."

In 1869, he designed the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane (now known as the H. H. Richardson Complex) in Buffalo, the largest commission of his career and the first appearance of his eponymous Richardsonian Romanesque style. A massive Medina sandstone complex, it is a National Historic Landmark and, as of 2009, was being restored.

The 1872 Trinity Church in Boston solidified Richardson's national reputation and led to major commissions for the rest of his life. Although incorporating historical elements from a variety of sources, including early Syrian Christian, Byzantine, and both French and Spanish Romanesque, it was more "Richardsonian" than Romanesque. Trinity was also a collaboration with the construction and engineering firm of the Norcross Brothers, with whom the architect would work on some 30 projects.

He was well-recognized by his peers; of ten buildings named by American architects as the best in 1885, fully half were his: besides Trinity Church, there were Albany City Hall, Sever Hall at Harvard University, the New York State Capitol in Albany (as a collaboration), and Town Hall in North Easton, Massachusetts.

Despite the success of Trinity, Richardson built only two more churches, focusing instead on the monumental buildings he preferred, plus libraries, railroad stations, commercial buildings, and houses. Of his buildings, the two he liked best, the Allegheny County Courthouse (Pittsburgh, 1884-1888) and the Marshall Field Wholesale Store (Chicago, 1885-1887, demolished 1930), were completed posthumously by his assistants.

Richardson died in 1886 at age 47 of Bright's disease, a historical term for the kidney disorder chronic nephritis. On his last day, he signed an informal will directing the three assistants still remaining to carry on the business, which was soon formalized as Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge.

Despite an enormous income for an architect of his day, his "reckless disregard for financial order" meant that he died deeply in debt, leaving little to his widow and six children. He was buried in Walnut Hills Cemetery, Brookline, Massachusetts.

Richardson spent much of his later years in his house in Brookline, Massachusetts, which had a studio attached to ease the strain on his health. The house fell into disrepair and was listed in 2007 as an endangered historic site. However, the house was purchased in January 2008 for roughly $2 million with an amended deed requiring that the building be historically restored. The house is on a hill, where Richardson could supposedly watch construction of the Trinity Church in Copley Square, from his second story window.

Richardson's most acclaimed early work is Trinity Church.The interior of the church is one of the leading examples of the arts and crafts aesthetic in the United States. It was at Trinity that Richardson first worked with Augustus Saint Gaudens, with whom he would work many times in the ensuing years. Across the square is the Boston Public Library, built later (1895) by Richardson's former draftsman, Charles Follen McKim. Together these and the surrounding buildings comprise one of the outstanding American urban complexes, built as the centerpiece of the newly developed Back Bay.

The Thomas Crane Public Library (Quincy, Massachusetts) is seen as Richardson's best library. Note the Japanese inspired eyelid dormers in the roof to each side of the entrance.

Richardson pointedly claimed ability to create any type of structure a client wanted, insisting he could design anything "from a cathedral to a chicken coop." "The things I want most to design are a grain elevator and the interior of a great river-steamboat." However, architectural historian James F. O'Gorman sees Richardson's achievement particularly in four building types: public libraries, commuter train station buildings, commercial buildings, and single-family houses.

The noted Marshall Field Wholesale Store (Chicago, 1885-1887, demolished 1930) is Richardson's "culminating statement of urban commmercial form", and its remarkable design influenced Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, and many other architects. According to Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, who has compiled all of Richardson's architectural works, despite its demolition in 1930, the Marshall Field Wholesale Store "is probably the most famous of Richardson's buildings, one that Richardson himself saw as among his most significant." Architectural critic Henry-Russell Hitchcock states that in the Field Store, Richardson "was, perhaps, never more creative architecturally."

Drawing from his own earlier work and both Romanesque and Renaissance precedents, Richardson designed this "massive but integrated" seven-story stone warehouse. Minimizing ornamentation in an era that employed lots of it, he stressed what he termed "the beauty of material and symmetry rather than mere superficial ornamentation" with "the effects depending on the relations of 'voids and solids'... on the proportion of the parts."Not requiring the new steel frame technology because of its comparatively low height, Richardson used multi-storied windows topped by arches to tie the stories together, and the regular patterns of the windows to tie the entire building into "a simple and unified solid occupying an entire block."

Richardson is one of few architects to be immortalized by having a style named after him. "Richardsonian Romanesque", unlike Victorian revival styles like Neo-Gothic, was a highly personal synthesis of the Beaux-Arts predilection for clear and legible plans, with the heavy massing that was favored by the pro-medievalists.

Significant to Richardson's style was his picturesque massing and roofline profiles, along with his mastery of rustication and polychromy, semi-circular arches supported on clusters of squat columns, and round arches over clusters of windows on massive walls.

Following his death, the Richardsonian style was perpetuated by a variety of proteges and other architects, many for civic buildings like city halls, county buildings, court houses, train stations and libraries, as well as churches and residences.