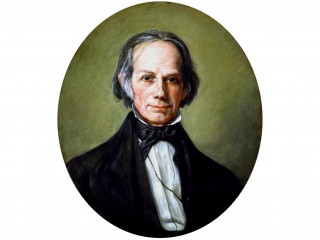

Henry Clay biography

Date of birth : 1777-04-12

Date of death : 1852-06-29

Birthplace : Hanover County, Virginia, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-06-09

Credited as : Politician and Lawyer, ,

5 votes so far

Henry Clay (1777-1852) was a paradox. An eloquent speaker known for charm and generosity, Clay served in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate, as well as U.S. Secretary of State. He also ran for the presidency five times and lost each time. Clay was a leader of the "War Hawks"--a group that pushed Congress to declare war against Britain in 1812--but he opposed the war against Mexico and did much to avoid civil war in the United States. Though Clay was a slave owner and often spoke in support of the slavery dominated South, he also helped craft the compromise that kept slavery out of new U.S. territories.

The son of Reverend John Clay, a Baptist minister, and Elizabeth Hudson Clay, Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, in Hanover County, Virginia. British and Loyalist soldiers raided the area during the American Revolution (1775-1783) and looted the Clay home in 1781. That year, the elder Clay also died. Henry Clay's mother remarried when he was fourteen. Clay's stepfather moved the family to Richmond. With only three years of formal schooling, Clay began working as a store clerk at his stepfather's recommendation.

From 1793 to 1797, Clay worked as secretary to George Wythe, chancellor of the High Court of Chancery. As secretary, Clay copied and transcribed records. Wythe encouraged Clay to continue his education, and in 1796 Clay took up the study of law under the Attorney General of Virginia, Robert Brooke. At age twenty, Clay graduated and immediately relocated to Kentucky, where his mother had moved. Frontier land disputes were fertile territory for a young lawyer, and Clay became well known as a defense attorney. He married into a leading family when he wed Lucretia Hart in 1799; they had 11 children. Clay prospered, and eventually owned a 600-acre estate, which he called "Ashland."

Henry Clay was tall and slim, with an expressive face, warm spirit, and personal charm. He had an excellent speaker's voice and became well known for his skill as an orator. Clay fought duels in 1809 and 1826. He lived the life of a frontiersman, and was prone to drinking and gambling. John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) noted that Clay was "half-educated," but that he possessed "all the virtues indispensable to a popular man."

Clay eventually became involved in politics. He participated in the constitutional convention for Kentucky in 1799, and in 1803 was elected to the Kentucky Legislature. He was appointed to two terms in the U.S. Senate, first from 1806 to 1807 and again from 1810 to 1811. Clay was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1811 and was immediately chosen to be Speaker of the House, a position he held six times during his tenure in the House, which lasted until 1821. In that year, Clay made his first bid for the presidency. From 1825 to 1826 he served as Secretary of State in the Cabinet of President John Quincy Adams (1825-1829). He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1831, where he served until 1842.

Clay was a lifetime advocate for business and protectionism. He pushed for federal support of infrastructure such as roads and canals. He developed the "American System," a program to improve home manufacturing and business. It was Clay's intention to unite the commercial and manufacturing interests of the East with the agricultural and entrepreneurial interests of the West. The American System was intended to establish protection for U.S. industries against foreign competition and also centralize financial control in the U.S. Bank. Clay backed the Tariff of 1816 and the annexation of West Florida by President James Madison (1809-1817). His protectionism reached its peak in the Tariff of Abominations in 1828.

As a nationalist and an expansionist, Clay advocated war with Britain in 1812 due to the British trampling of U.S. rights on the high seas. The "War Hawks" as they were known, supported the War in 1812 (1812-1814). Clay supported the Latin American rebellions against the Spanish, and the Greek rebellion against the Turks. He was not in favor of war with Mexico, but supported the government nonetheless, losing one of his sons in the Battle of Buena Vista (1847).

Clay worked hard but unsuccessfully in the Kentucky constitutional convention to abolish slavery in the new state. He never reconciled his attitudes over slavery, defending the southern states on the one hand and owning slaves himself, but working hard for slavery's abolition on the other hand. At his death, his 50 slaves were willed to his family, but with the provision that all children of these slaves after January 1, 1850, be liberated and transported to Liberia. Clay was a founder of the American Colonization Society in 1816--a society that advocated the repatriation of slaves to Africa.

As an expansionist Clay worked for the addition of states and territories to the Union. A lifelong proponent of the ideals of the American Revolution (1775-1783), he worked for the preservation of the Union. He supported the Missouri Compromise, which allowed Missouri to enter the Union as a slave state while preventing slavery above the 36th parallel. He personally acquired the assurance of the Missouri Legislature that it would not pass any laws that would affect the rights and privileges of U.S. citizens. During the Missouri debates, Clay argued the side of the southern States, continuing the dualism that would be present throughout his life--advocating the rights of slave states while working at the same time to abolish slavery.

In 1849, aligned with statesman Daniel Webster (1782-1852), Clay advocated the Compromise of 1850, which was credited as postponing the American Civil War (1861-1865) for a decade. The compromise was actually a series of proposals that admitted California to the Union as a free state, abolished slavery in the District of Columbia, set up the territories of New Mexico and Utah without slavery, and established a more rigorous fugitive slave law.

Clay ran unsuccessfully for the presidency five times. He was a fearless fighter for his ideas, even if his positions on issues were primarily based on his own self interests. He was devoted to the Union, even if his compromises only postponed an inevitable clash between the North and the South. He considered himself an advocate of Jeffersonian democracy and was involved in party politics, including the establishment of the Whig party. He owned slaves, advocated the removal of blacks from the United States, and worked continuously for the abolition of slavery. As such a self-contradictory individual, Clay had as many fervent supporters as he did enemies.

Henry Clay was well respected by ordinary citizens. In his old age Clay was considerably in debt and when it became known that he was thinking of selling his beloved estate Ashland, common people donated enough money to clear his debts. Few of Clay's children survived him; many did not live to maturity. His son Thomas was ambassador to Guatemala under President Abraham Lincoln (1861-1865). His son James was charge d'affairs at the U.S. embassy in Portugal under President Zachary Taylor (1849-1850). Clay left no surviving descendents, however, when he died in Washington, DC, on June 29, 1852.