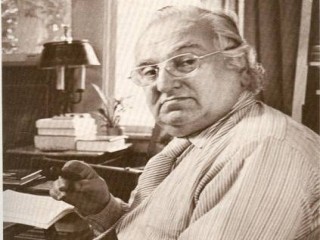

Harry Golden biography

Date of birth : 1902-05-06

Date of death : 1981-10-02

Birthplace : Mikulintsy, Ukraine

Nationality : Jewish-American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-06-06

Credited as : Humorist, writer and publisher, Only in America

The Jewish-American humorist Harry Golden was writer and publisher of the Carolina Israelite and author of many popular books including Only in America.

Harry Golden, born in 1902, was the son of Leib and Anna Klein Goldhirsch. Although many references identify Golden's birthplace as New York City, his autobiography says that his father and his oldest brother left their home in Milulintsy, a village in eastern Galicia, then part of the Austria-Hungary Empire, and migrated to Canada and, after brief stays in other places, saved money to bring Golden and his mother and sister to New York City in 1905. Immigration officials at Ellis Island changed the surname to Goldhurst. Golden grew up in the poor but culturally rich Jewish ghetto of New York City's Lower East Side, where his father earned a living as a teacher of Hebrew and as a freelance writer. His mother, born in Rumania, was pious and prayerful, but illiterate. The father, a rationalist in religion, nonetheless kept strict Sabbath observances and greatly influenced his son's intellectual development.

Golden attended Public School 20 and found especially exciting the lively evening classes for immigrant children. He was an eager learner and prolific reader and carried his enthusiasm through the completion of his formal education at the City College of New York. Thereafter, Golden engaged in several kinds of work, most significantly as a floor boy with the furrier company owned by Oscar Geiger, a devotee of the reformer Henry George. Golden worked for Geiger's senatorial campaign as candidate of the Single Tax party in 1924.

Golden soon found himself in the stock market business, employed in his sister Clara's firm. In 1926 Golden began his own business, Kable and Company, selling stocks and bonds on the partial payment plan. But Golden turned this operation into a lucrative "bucket shop" that speculated on the stock purchases of his clients and skimmed off profits on the rise and fall in the market value of the stocks.

The best-known client of the firm was Bishop James Cannon, Jr., of the Methodist Episcopal Church, who was morally compromised with Golden in these speculations. Golden was brought to trial and served a three-year prison sentence from 1929 to 1932.

Upon completion of his sentence Golden worked at his brother's Hotel Markwell on Manhattan's west side. Throughout the 1930s, as the menace of Nazism grew in Germany, Golden took a new and deep interest in Jewish history and culture, immersing himself in the literature of these subjects. Then in 1941 he left New York, moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, and changed his name to Golden. He joined the staff of the Charlotte Labor Journal and became familiar as a partisan of the union movement in a part of the country where that cause was often equated with communism. He then became a successful salesman of advertising space for the Charlotte Observer and decided on a bold adventure in publishing his own newspaper.

The Carolina Israelite, which first appeared in October 1942, became an exceptional and noteworthy publication. Golden produced the paper in two old homes in Charlotte, writing all of it, often in a fit of energy, and issued it when he was ready. It was a Jewish enterprise that grew to influence in a part of the country where Jews were not in great number, and in fact most of its circulation, soon reaching 16,000, was in the major cities—New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia. Also, the Carolina Israelite espoused liberal social and political views, most controversially on racial integration and labor, in an area where these issues were explosive. But Golden was developing at the same time the soft touch and humor that enabled him to support these causes in a manner that did not induce hatred toward him in return. Golden spoke at different places in the South as he worked for the civil rights movement, and in Atlanta he was asked a familiar question: "What's a Jew doing down here trying to change the Southern way of life?" Golden replied: "I am trying to organize a Jewish society for the preservation of Christian ethics." The Atlanta audience, Golden reported, cheered.

Golden gathered many of his Carolina Israelite essays into a book, Only in America, published in 1958. It was a success and made Golden a national name. The earnings from the book supported the newspaper at a time when Golden's unpopular views on integration prompted withdrawal of advertising and loss of support from worried merchants, many of them Jewish. Also, in the midst of his newly won fame Golden's background and real identity were exposed in an anonymous letter to his publisher. But Golden outrode the revelation and continued in the national limelight. He was a frequent guest on national television programs, a contributor to journals such as The Nation and Commentary, with special assignments from LIFE, and a popular lecturer around the country. The television exposure also swelled the subscription lists of his newspaper.

Only in America and other books that followed in similar format placed Golden in the traditions both of the native humorist, such as Will Rogers, and the ethnic humorist, such as Peter Finley Dunne and Sam Levenson. Golden seemed to appeal to an American reading audience that felt the necessity for conformity and affirmation of its way of life and at the same time feared the decline of cultural pluralism. Golden's Jewish identity to that extent enhanced his appeal. He symbolized the contemporary Jew who had left the ghetto behind and was at home in middle-class America. If his humor chastized, it did so with a loving touch and always with a moral lesson that reminded Americans of their traditional idealism.

Golden's various schemes for solving the racial problem in America were most memorable. Observing that white Southerners were loathe to sit with African Americans on busses or in restaurants, but noting that whites often stood in line with African Americans at grocery stores and other places, Golden called on the public school to remove all chairs from their classrooms. This "Vertical Negro Plan" would thereby overcome Southern reservations about sitting in the same room with the other race. Golden's "White Baby" plan would pave the way for integration of Southern theaters and movie houses by arranging for African Americans to enter these places carrying a white baby.

By the end of the 1960s Golden had turned away from the extremist side of the African American movement, denouncing the militant voices in it. He closed the Carolina Israelite in 1968. He also resigned from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) because of its opposition to Israel. But Golden remained a committed Democratic party liberal and, having assisted earlier in the campaigns of Adlai Stevenson, he supported the candidacies of John F. Kennedy and Robert Kennedy. Although an immensely popular writer, Golden was criticized, most often by other Jewish spokesmen who found his manner of addressing social problems and anti-Semitism too frivolous, disarming, and sentimental. Harry Golden died in 1981.

Golden once said that he was assisted throughout his writing career by an unfailing memory. That quality of mind characterized his autobiography, The Right Time, which is often rich with observations of Jewish life in New York City and of Southern mores, but which suffers from an excess of detail. Golden books that followed Only in America include For 2 Plain (1959), You're Entitle' (1962), and Ess, Ess Mein Kind (1966). The Best of Harry Golden (1967) is an anthology of his writings. A handsome book with many photographs is Golden's The Greatest Jewish City in the World (1972) about Jewish culture in New York. Other subjects on which Golden wrote are found in Carl Sandburg (1961), Mr. Kennedy and the Negroes (1964), and The Israelis (1971). An essay on the Harry Golden phenomenon is Theodore Solotaroff, "Harry Golden & the American Audience," in Commentary (March 1961).