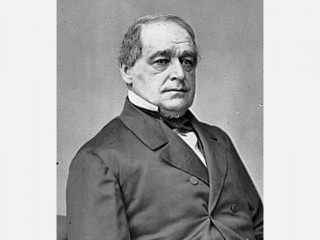

Hannibal Hamlin biography

Date of birth : 1809-08-27

Date of death : 1891-07-04

Birthplace : Maine, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-06-08

Credited as : Vice-president, President Abraham Lincoln,

1 votes so far

He was a descendant in the fifth generation from James Hamlin who settled in Barnstable County, Mass., about 1639. His father, a twin brother of Hannibal Hamlin, the father of Cyrus [q.v.], had studied medicine at Harvard, but after taking up land in Maine, combined farming with the practice of his profession and the holding of sundry local offices. Hannibal grew up in the wholesome environment of a good New England home and attended the village school and Hebron Academy in preparation for college. The latter project had to be abandoned, owing to family misfortunes, and after trying his hand at surveying, printing, and school teaching for a brief period, he decided to study law. He was fortunate in being able to enter the office of Fessenden & Deblois of Portland, the senior partner of which firm, Samuel Fessenden [q.v.], was at once the leading lawyer and the outstanding anti-slavery advocate of the state. Hamlin was admitted to the bar in 1833 and in the same year settled at Hampden, not far from Bangor. He acquired a considerable practice, but his pronounced talent for party work soon diverted his attention to a political career. As a Jacksonian Democrat, he represented Hampden in the legislature from 1836 to 1841 and again in 1847. He served as speaker for three terms, 1837, 1839-40. The legislature, during his first five years of service, was an especially valuable training school, containing many members afterwards distinguished in state and national affairs and dealing with such important matters as the financial demoralization of 1837 and succeeding years, the Aroostook boundary embroglio, the abolitionist agitation, and the internal-improvement craze. Hamlin's attitude was usually cautious and conservative.

In 1842 he was elected to Congress and served without special distinction from Mar. 4, 1843, to Mar. 3, 1847. He had decided anti-slavery leanings but, like many of his contemporaries, regarded slavery as an institution beyond the legislative authority of the national government. It is to his credit, however, that he opposed the attempts of its supporters to suppress free discussion. The growing importance of this question eventually produced a serious schism in the Maine Democracy, and in 1848 Hamlin was elected to the United States Senate to serve the balance of the term of John Fairfield, deceased, by the anti-slavery wing of the party. He was reëlected in 1851 for a full term. Although a popular campaign orator, he preferred, as he afterwards stated, to be "a working rather than a talking member" of the Senate. As chairman of the committee on commerce he was the author of important legislation dealing with steamboat licensing and inspection and shipowners' liability. Though a supporter of Pierce in 1852, he became increasingly dissatisfied with the Democratic policy toward slavery, and in 1856 went over to the Republicans. His speech of June 12, 1856, in which he renounced his Democratic allegiance, was widely quoted for campaign purposes and was one of his most effective utterances (Congressional Globe, 34 Cong., 1 Sess., pp. 1396-97). In the same year he was elected governor of Maine in an exciting contest which marked the beginning of a long period of Republican predominance. He served only a few weeks as governor, resigning from the Senate Jan. 7, 1857, only to resign the governorship in the following month in order to begin a new term in the Senate. He became increasingly prominent in the anti-slavery contest, and the political needs of 1860 made him a logical running mate for Lincoln. He again resigned from the Senate on Jan. 17, 1861.

As vice-president during the Civil War, he presided over the Senate with dignity and ability, was on cordial terms with President Lincoln, and performed a great variety of wartime services for his former constituents in Maine. He was a strong advocate of emancipation and became identified with the "Radicals" of Congress. If his nomination in 1860 had been due largely to party exigencies, his failure to receive a renomination in 1864 may be attributed to the same causes. After retirement from the vice-presidency, he served for about a year as collector of the port of Boston, resigning because of his disapproval of President Johnson's policy. After two years as president of a railroad company constructing a line from Bangor to Dover, he was reëlected to the Senate, serving from Mar. 4, 1869, to Mar. 3, 1881. He was associated with the Radical group in reconstruction matters, supported Republican principles in economic issues, and steadily maintained his hold on the party organization of his native state. He was an influential opponent of the third-term movement for Grant in the convention of 1880. After retirement from the Senate he served as minister to Spain for a brief period (1881-82), an appointment of obviously complimentary character, without diplomatic significance. He spent his last years in Bangor, enjoying a wide reputation as a political Nestor and one of the last surviving intimates of President Lincoln.

Hamlin is usually grouped with the members of that remarkable dynasty of Maine statesmen beginning with George Evans and ending with Eugene Hale, all of whom he knew and some of whose fortunes he undoubtedly influenced. As a party manager and leader he did not display the unflinching courage and determination of William Pitt Fessenden or Thomas B. Reed, nor that mastery of a wide field of legislation possessed by George Evans or Nelson Dingley. He had, however, a great fund of shrewd common sense and a gift of stating things in clear and understandable phrase. When as chairman of the committee on foreign relations he urged the acceptance of the Halifax fisheries award in the interest of international arbitration and when, on the floor of the Senate, he opposed the Chinese exclusion law as a violation of treaty obligations (Congressional Record, 45 Cong., 3 Sess., pp. 1383-87), he displayed genuine statesmanship. It is also worth mention that if he quarreled with President Hayes over patronage and expressed his contempt for civil-service reform, he at least opposed the infamous "salary grab" and refused to take his share of the loot.

Personally Hamlin had many attractive qualities and retained the loyalty and affection of a host of supporters. Senator Henry L. Dawes, who knew him well, described him as "a born democrat," an interesting conversationalist, and an inveterate smoker and card player. He also mentioned as characteristic of the man that he wore "a black swallow-tailed coat, and . . . clung to the old fashioned stock long after it had been discarded by the rest of mankind" (Century Magazine, July 1895). Hamlin had a stocky, powerful frame and great muscular strength. His complexion was so swarthy that in 1860 the story was successfully circulated among credulous Southerners that he had Negro blood. He was a skillful fly fisherman and an expert rifle shot. He was twice married: on Dec. 10, 1833, to Sarah Jane Emery, daughter of Judge Stephen A. Emery of Paris Hill, who died Apr. 17, 1855, and on Sept. 25, 1856, to Ellen Vesta Emery, a half-sister of his first wife. Charles Hamlin [q.v.] was his son.