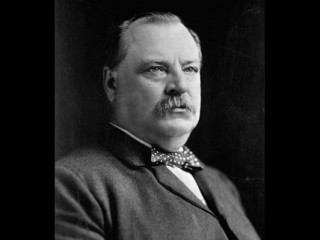

Grover Cleveland biography

Date of birth : 1837-03-18

Date of death : 1908-06-24

Birthplace : Caldwell, New Jersey, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-10-06

Credited as : Politician, former U.S President, preceded president Chester Arthur

10 votes so far

"The lessons of paternalism ought to be unlearned and the better lesson taught that while the people should patriotically and cheerfully support their Government, its functions do not include the support of the people."

Strong but conservative reform Democrat, who was the only American political leader to serve two separate terms as president.

* 1855 Moved to Buffalo to begin training for the practice of law

* 1870 Elected sheriff of Erie County in western New York

* 1881 Elected mayor of Buffalo, New York

* 1882 Elected governor of New York State

* 1884 Elected president of U.S., defeating Republican James G. Blaine

* 1887 Annual message to Congress devoted entirely to a call for tariff reform

* 1888 Defeated in try for re-election by Republican Benjamin Harrison

* 1892 Elected president for the second time, defeating Harrison

* 1893 Inaugurated just as the worst depression of the 19th century set in; underwent secret operation to remove cancerous tumor from jaw

* 1894 Dispatched federal troops to Chicago to suppress a major strike by rail workers

* 1895 Demanded arbitration of Venezuela boundary dispute with Great Britain

* 1897 Retired from public office

Born Stephen Grover Cleveland on March 18, 1837, in Caldwell, New Jersey; died on June 24, 1908, in Princeton, New Jersey; son of Richard Falley (a Presbyterian minister) and Anne (Neal) Cleveland; married: Frances Folsom; children: three daughters, Ruth, Esther, Marion, and two sons, Richard and Francis. Predecessor: Chester Arthur. Successor: William McKinley.

Grover Cleveland was born in New Jersey but spent most of his boyhood in the canal country of upstate New York, at Fayetteville, where his father, a Presbyterian minister, was called to serve a small church in 1841. One of nine children growing up in a respectable household short on money, young Cleveland experienced a frugal, hard-working youth. Family training as a preacher's son instilled in him stern rules about Protestant morality and right behavior as well as a streak of stubborn independence that marked his nature all his life. A strapping, self-sufficient lad, he mixed his formal schooling with odd jobs, long hours of solitary fishing, and an occasional excursion along the Erie Canal.

He was 16 when his father died unexpectedly, leaving the family in genteel poverty, and ending hopes of college for the son. In 1855, following an unhappy year in New York City teaching at a school for the blind, Cleveland headed west across the state to settle in Buffalo, a rough, raw, fast-growing city on Lake Erie. After serving an apprenticeship at a downtown law firm, he launched his own practice and soon acquired a reputation for sound, unspectacular, reliable diligence. During the Civil War years he avoided military service by hiring a substitute, enjoyed the after-hours saloon life of a young urban bachelor, and increasingly involved himself in the legwork of local Democratic Party politics. "The Party of Personal Liberty," as Democrats called it in those days, appealed to his independent nature and allied him with influential Party friends among German, Irish, and other ethnic groups in the city. But he was also a stern believer in public law and order, and in 1870 he won election to a three-year term as sheriff of Erie County, a job that deepened his instinct for strict enforcement of public rules.

In 1874, Cleveland resolved an awkward problem of moral law and order by acknowledging paternity of a baby born to a young widow, Maria Halpin, whom he had befriended. This episode would cloud his reputation for propriety a decade later when scandalmongers exposed it after his nomination for the presidency in 1884. His terse response to the scandal when it broke would be simply, "Tell the truth."

Cleveland's knack for "telling the truth" as he believed it---bluntly, stubbornly, and even somewhat righteously---improved his political stock throughout the 1870s. Meanwhile, his solid law practice won him growing numbers of admirers among Buffalo's professional elite. By the end of that decade, he was poised for political takeoff. In 1881, the sorry state of Buffalo's government, which like that of so many American cities in the Gilded Age was graft-ridden and inefficient, provoked a reform drive that climaxed in Cleveland's election as mayor. Promptly rewarding his supporters with a striking display of executive stubbornness, he vetoed dubious municipal contracts and curbed public-spending habits. When people began calling him the "veto mayor," leaders of the statewide Democratic Party picked up their ears. In 1882, eager to regain the New York governorship, they named Cleveland as their nominee. He won the election by a wider margin than any in the past, trading on his public image as a strong, straightforward, honest man.

As governor, he confirmed the expectations aroused by his mayoralty. Again he used his executive veto power as a whiplash against sloppy bills passed by the legislative branch. His quarrels with New York City's Tammany Hall machine politicians over Party patronage, and his support for a state civil service reform law, the first in the country, aligned him against the notorious "spoils system" for distributing public jobs and won him applause from political independents and even some Republicans. By 1884, his record of moderate success as governor of the nation's most populous state made him an odds-on favorite to head his Party's presidential ticket, despite angry opposition from Tammany Hall. "We love him most of all for the enemies he has made," a Cleveland supporter replied to Tammany's protest at his nomination.

Cleveland Is Elected President by Narrow Margin

The 1884 presidential contest pitted Cleveland, a newcomer to national politics, against James G. Blaine, a seasoned Republican Party leader whose long experience in Washington's inner circles had stained him with charges of corruption. These charges persuaded many prominent Republican independents, called Mugwumps, to make a well-publicized bolt from Blaine to Cleveland, offsetting Blaine's popularity among normally Democratic Irish Catholics. After an unusually dirty campaign of accusations about the rival candidates' personal flaws, Cleveland squeaked through to victory by a very narrow margin.

When Cleveland arrived in Washington to take office, he was 47 years old. A ponderous, thick-bodied man of medium height, weighing over 250 pounds, he was inclined to plain simplicity in food, clothing, and manner, not much for public ceremony or close political friendships, and intent on carrying out his duties as a public trust. The first Democrat elected to the White House in 28 years, he was immediately besieged by Democratic officeseekers hungry for the spoils of Party victory. Meanwhile, Mugwump civil service reformers insisted on his support for their campaign to curb the hunt for spoils by imposing a merit system on the federal bureaucracy. Cleveland labored long and hard during his first years in office to balance off these clashing expectations and to improve the quality of public service through his appointments.

He also struggled with some success to assert the independence of the executive branch from interference in its operations by entrenched congressional politicians of both parties. But only rarely did he use his presidential power to promote and shape congressional legislation or to influence public opinion through the press. He defined his duties in more negative terms, as he had earlier as mayor and governor, to prevent wrongdoing in public affairs and thus sanitize the federal government. "Our stock in trade you know is absolute cleanliness," he told a friend after one year in office. And his administration was refreshingly free of scandal.

A striking example of his effort to purge longstanding political practices on Capital Hill was his decision to veto private pension bills passed by Congress for Civil War veterans whose claims on the government he regarded as weak or fraudulent. No previous president had given these bills such close scrutiny, and his policy provoked much outcry from those who regarded the surplus in the federal treasury as an easy source of public welfare. His insistence on minimal government support for needy citizens of all kinds, including drought-stricken western farmers, confirmed his reputation for social conservatism and limited his personal popularity.

In June 1886, however, Cleveland delighted White House watchers by ending his bachelor days and marrying Frances Folsom, a pretty 22-year-old tennis-playing college graduate whom he had known since her infancy in Buffalo. Bringing a needed warmth and sparkle to his life, she gave birth to five children over the next 17 years. Not even trumped-up partisan charges in the press about Cleveland's drunken wife-beating dimmed the satisfactions of their marriage.

Tariff Issue Contributes to His Defeat

Cleveland's most important reform initiative during his first term came near its close, when he devoted his entire annual message to Congress in December 1887 to a call for downward revision of federal tariffs on imported goods. High tariff protection for American "home industries" had been a keystone of Republican Party economic policy since the Civil War, and tariff revenues had helped swell the treasury surplus which Cleveland wanted to reduce. Though no free trader, he believed that tariff protection from foreign competition fattened the profits of corporate monopolies, while raising retail prices for ordinary citizens. His tariff argument made him the first president to define wage earners as the consumers of the goods they produced, and his focus on the interests of consumers was an important contribution to subsequent tariff debate. But Cleveland failed to unite the Democratic Party around the cause of tariff reduction, and a deadlocked Congress took no action. In the presidential contest of 1888, Republican spokesmen aggressively promoted continued high tariff protection, putting Cleveland on the defensive. He shunned speechmaking, and Party managers campaigned ineffectively for his reelection. He lost to Republican Benjamin Harrison in the electoral college vote, even though he won a plurality in the popular vote. To those who argued that his low-tariff position had ruined his chances, he replied, "Perhaps I made a mistake from the party standpoint; but damn it, it was right."

Over the next four years, while practicing law in New York City, Cleveland maintained good relations with the eastern, conservative wing of his Party, quietly positioning himself for a presidential renomination on the strength of his tariff reform stance and the mystique of blunt, reliable honesty that surrounded him. He also spoke out against the rising demand of debt-ridden southern and western farmers for currency inflation through the coinage of silver. Although the growing American economy of the late 19th century was in need of a larger money supply in circulation, Cleveland regarded unilateral silver inflation by the United States as a threat to national and global financial stability. Overcoming factional division on these issues, he was again tapped as his Party's choice and won re-election to the White House in 1892. He had now secured his third straight national plurality in the popular vote, a feat surpassed in presidential history only by Franklin D. Roosevelt. Cleveland's rock-hard strength of purpose seemed to many contemporaries, even those who disagreed with him, to be a valuable national resource.

But his return to office was shadowed by harsh personal and political problems. In July 1893, he underwent a secret operation for removal of a large malignant growth in his jaw, and though the surgery proved successful, it greatly sapped his executive resilience thereafter. Moreover, his second presidency coincided almost exactly with the worst industrial depression of the 19th century, which was triggered by a wave of commercial bankruptcies, a withdrawal of investments by frightened foreign capitalists, and an accelerating flow of gold to Europe that threatened the gold reserve in the federal treasury. Cleveland's stubbornly conservative responses to the avalanche of crises spawned by the depression enabled him to maintain the integrity of the government's obligations as he understood them, but did little to cushion the miseries of deepening factory unemployment and agricultural distress. As in the past, his decisions were characteristically more prudent and preventive than they were generous and imaginative.

His initial decision was to force through Congress a repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, in order to stabilize the currency and shore up the nation's gold supply, which was jeopardized by the operations of the Act. His arm-twisting tactics to win repeal in the name of "sound money" offended many of his fellow Democrats, as did his subsequent negotiations with Wall Street bankers led by J.P. Morgan to further strengthen gold reserves by selling gold bonds overseas.

When Cleveland returned to Congress with a call for tariff reform, still his favorite remedy for the country's economic ills, he learned that his political clout and credibility on Capitol Hill were largely exhausted. Owing to intense lobbying by protectionist interests in the Senate, the Wilson-Gorman Tariff of 1894 fell so far short of Cleveland's hopes for substantial tariff reduction that he refused to sign the bill as it passed into law. Thus his long drive for tariff reform came to a limp conclusion and would not be revived until two decades later, when the next Democrat to live in the White House, Woodrow Wilson, would pursue the issue much more effectively.

Coxey's "Army", Pullman Strike Challenge Cleveland

The depression of 1893--97 slumped to its worst depths in 1894. Wage cuts, factory closings, and spreading unemployment provoked a mixture of despair and militance among blue-collar Americans. Cleveland perceived this restlessness mainly as a threat to law and order. When Jacob Coxey led an "army" of his followers on a well-publicized march to Washington to promote his visionary proposal for a federal road-building program to combat unemployment, the government responded with cold mistrust and dispersed the marchers when they reached the Capitol. A more serious challenge to Cleveland's sense of public order was the great Chicago Pullman strike of 1894. Workers at the Pullman sleeping car company went on strike to protest a slash in wages, and the American Railway Union, led by Eugene Debs, joined them in a sympathy strike, thus paralyzing rail traffic through Chicago. After Cleveland's Attorney-General Richard Olney secured a federal injunction against the strikers to prevent disruption of train and mail service, the president ordered troops into the city to maintain order. "If it takes the entire army and navy of the United States to deliver a post card in Chicago," Cleveland said, "that card will be delivered." Mob violence gripped the city for several days thereafter, but the strike was broken, and Debs was arrested and jailed for ignoring the antistrike injunction. "In this hour of danger and public distress," Cleveland announced in justification of his stern measures, what was needed was "active efforts on the part of all in authority to restore obedience to the law and to protect life and property." Debs came out of jail embittered by the government's action and went on to become the country's leading socialist. The Pullman strike dramatized a vivid conflict between the emerging tactics and aspirations of organized labor and the repressive force of Cleveland's response.

In the history of American politics, the party in power when a depression hits usually suffers at the next election. Cleveland's Democratic Party paid the price in the congressional elections of 1894, losing over 100 seats to resurgent Republicans. Thereafter Cleveland, ever more reclusive in the White House, was seen by his critics to be seriously discredited as a Party leader. In 1895, he gained a momentary surge of popular support in the field of foreign policy by stating in belligerent language the United States' interest in resolving a South American boundary between Venezuela and British Guiana. This assertion of America's traditional authority under the Monroe Doctrine to interpose itself against European power in the New World, and Cleveland's insistence on forcing Great Britain to accept arbitration of the dispute, sounded a note of diplomatic aggressiveness which many Americans welcomed as an Anglophobic twist of the lion's tail. As it turned out, however, the peaceful resolution of the Venezuela boundary dispute set the stage for much more cordial and cooperative relations between Britain and the United States in the decades ahead.

Cleveland's political standing at home plummeted during the presidential election year of 1896. By then a sharp split had opened between Cleveland's beleaguered conservative allies in the Democratic Party and increasingly radicalized Democrats in the South and West, who were attracted by the wide appeal of agrarian Populism in those regions. Cleveland scorned Populist reform doctrine, not only its inflationist call for unlimited silver coinage but its demand for expanded governmental regulation of the private economy in the interest of common working people. But as his presidency wound down, he could do little to ward off the influence of Populist thought on his own Party. The Democratic convention of 1896, controlled by agrarian insurgents, adopted a platform that repudiated Cleveland's leadership and nominated his rising young Party rival, the eloquent exponent of free silver, William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska. Cleveland was greatly relieved by Bryan's subsequent defeat at the polls by the Republican nominee, William McKinley.

He was also greatly relieved to leave the White House. Several years earlier, Cleveland had written to a friend, "I am suffering many perplexities and troubles and this term of the Presidency has cost me so much health and vigor that I have sometimes doubted if I could carry the burden to the end." Now that the burden lifted, he moved to Princeton, New Jersey, to pursue a busy and satisfying retirement. He kept a close watch on public affairs and was prominent among anti-imperialist critics of the overseas expansionism that marked McKinley's presidency. By the time of his death in 1908, Cleveland had regained much of the national respect that he had enjoyed before the political disasters of his second presidency. His last words were, "I have tried so hard to do right."

Forty years later, a poll of historians ranked him among the "near great" presidents, just below Lincoln, Washington, Wilson, Jefferson, Jackson, and the two Roosevelts. In more recent polls, however, his standing has steadily declined. Cleveland's personal strengths were those that resonated with the celebrated values of the 19th-century Protestant middle class from which he sprang---discipline, square dealing, personal autonomy, attention to duty, and diligent hard work. These traits shaped his leadership and limited it. He was not very agile or enterprising or elastic on the job. The transforming 20th-century expansion in the powers of the presidency, and in the responsibility of the federal government to provide public remedies for social distress, make Cleveland's performance seem in retrospect to have been too often negative and narrow. In his own day, and on his own terms, he functioned consistently as a national sheriff of public law and order.