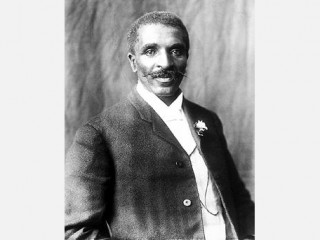

George Washington Carver biography

Date of birth : 1864-01-01

Date of death : 1943-01-05

Birthplace : Diamond, Missouri, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2010-07-13

Credited as : Scientist and botanist, discovery of alternative farming methods,

73 votes so far

George Washington Carver was an agricultural chemist who gained acclaim for his discovery of alternative farming methods. A widely talented man who was born into slavery and orphaned in infancy, Carver became an almost mythical American folk hero. He was a faculty member at the all-black Tuskegee Institute, where he worked to improve the lives of impoverished local farmers. Carver is best known for his discovery of uses for the peanut. His testimony in 1921 before the House Ways and Means Committee in support of a tariff to protect the U.S. peanut industry helped earn him the nickname the "peanut wizard."

Known as the "plant doctor"

George Washington Carver was born near the end of the Civil War (1861-65) in Diamond, Missouri. His mother, Mary, was a slave owned by Moses and Susan Carver, who were struggling homesteaders. His father, who is believed to have been a slave on a nearby plantation, was killed in an accident soon after Carver was born. Carver's mother disappeared following a kidnapping by bushwhackers, and he and his brother were then brought up by Moses and Susan. The Carvers were stern but kindly people who did their best for the brothers, despite their limited means.

As a young man Carver was too frail to do heavy farm work like his brother, so he helped his foster mother with household chores such as cleaning and sewing. He also spent considerable time indulging his deep curiosity for nature. He built a pond for his frog collection and kept a little plant nursery in the woods. Because of his talent with plants, Carver became known as the neighborhood "plant doctor."

Encounters discrimination

Carver desperately wanted to learn to read and write, but the local school did not accept black children. Consequently he left his foster parents when he was ten to attend the black school in the county seat of Neosho. This marked the beginning of his long journey through three states in pursuit of a basic education. During these years, Carver supported himself with odd jobs, working for and living with various families along the way. He was over twenty years old when he finally graduated from high school in 1885. That same year he was accepted as a student at Highland College in northeastern Kansas. When he arrived there ready to start classes, however, he was told that Highland did not accept students of color. Disillusioned and poor, Carver found work in a nearby fruit farm, mending fences and picking fruit.

Pursues higher education

In 1890, Carver began attending Simpson College at Indianola, Iowa. He had planned to study painting, but the art teacher, who recognized Carver's talent, also foresaw the difficulty a black man would have pursuing a career as a painter at the time. She suggested he consider a career in botany; her father was a professor at Iowa Agricultural College at Ames. Carver was admitted to that college the following year.

At Iowa, Carver was a popular student and became active in a variety of campus affairs. Because of his wide-ranging abilities he was affectionately called "doctor" by the other students. Carver's academic record was excellent, and his skills in raising, cross-fertilizing, and grafting plants were lauded by his professors. His bachelor's degree thesis, "Plants as Modified by Man," described the positive aspects of hybridization (interbreeding). Carver stayed on at Iowa for graduate work and was soon appointed an assistant in botany (the branch of biology that deals with plant life).

Joins Tuskegee administration

After Carver received his master's degree from Iowa in 1896, he was invited by respected African American educator and leader Booker T. Washington to become director of agriculture at Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama. The institute had been established by Washington in the 1880s as an industrial and agricultural school for black students, and Carver felt that this was where he was most needed.

Carver had many responsibilities at Tuskegee. In addition to heading the agriculture department, he directed the newly established Agricultural Experiment Station. He also assisted local farmers, who were desperately poor, by writing instructional pamphlets on farming. He even set up a movable school that traveled around the South to instruct farmers in agricultural methods.

When Carver started the movable school in 1906, it was no more than a mule-drawn cart. Soon he was driving a large truck, traveling from place to place with tools and exhibits to enhance his lessons. One of his aims was to persuade farmers to give up growing cotton (which was depleting the soil and bringing in very little money) and to diversify by growing vegetables, peanuts, and soybeans.

Contributes to "scientific agriculture"

In 1910, Washington transferred Carver from the agriculture department, appointing him director of a new research department and giving him the title "consulting chemist." Experimental work was more to Carver's liking. At the time, however, the resources at Tuskegee were limited. Carver had no proper laboratory, and he had to make his own equipment out of bits of wire, old bottles, and whatever else he could lay his hands on. He apparently enjoyed these challenges to his ingenuity; indeed, the lack of proper resources led to many of his inventions, for it forced him to find ways of improving the local agriculture in practical and inexpensive ways.

Carver was at the forefront of the new discipline of scientific agriculture, a field dedicated to the exploration of alternative farming methods. He focused his experimental research on finding ways to improve the lives of local farmers. He analyzed water, feed, and soil; experimented with paints that could be made with clay; worked with organic fertilizers; demonstrated uses for cheap and locally available materials, such as swamp muck; and searched for new, inexpensive foodstuffs to supplement the farmers' diets. In addition to human food items, Carver developed stock feeds, cosmetics, dyes, stains, medicines, and ink from peanuts and sweet potatoes.

The most important resource Carver researched was the peanut. He recognized the plant's value in restoring nitrogen to depleted southern soil--cotton crops exhausted the farmers' land--and publicized its high protein and nutritional value. Among the products Carver developed from peanuts were soap, face powder, mayonnaise, shampoo, metal polish, and adhesives--but he was not the one to invent peanut butter.

Gains recognition

In 1916, Carver received two prestigious invitations: to serve on the advisory board of the U.S. National Agricultural Society and to become a fellow of the Royal Society for the Arts in London. In 1919, he received his first salary increase in twenty years. He had become increasingly popular as a lecturer, and his testimony before the House Ways and Means Committee in 1921 concerning the importance of the peanut industry thrust him into the national limelight. Two years later Carver was awarded the prestigious Spingarn Medal from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for his contributions to agricultural chemistry. He was also honored for his lectures to religious, educational, and farming audiences--lectures that had "increased inter-racial knowledge and respect."

Becomes a spokesperson for "chemurgy"

In the mid-1930s, Carver became an advocate of "chemurgy," the process of putting chemistry to work in industry for the farmer. In 1937, he met industrialist Henry Ford at a chemurgy conference Ford had sponsored. A long friendship developed between the two men. Three years later, when Carver established the Carver Museum in Tuskegee (a foundation to continue and preserve his work), it was dedicated by Ford. The museum contains seventy-one of Carver's pictures as well as handicrafts, case studies, and results of his research.

Receives numerous awards and honors

In addition to the Spingarn Medal, Carver received numerous other awards and honors for his contributions to the field of scientific agriculture. Noteworthy among them are the Roosevelt Medal in 1939, an honorary doctorate from the University of Rochester, and the first award for "outstanding service to the welfare of the South" from the Catholic Conference of the South. In 1942, Ford erected a Carver memorial cabin and a nutritional laboratory in Carver's honor at Dearborn, Michigan's Greenfield Village.

Carver's health had begun to fail in the 1930s. When he died on January 5, 1943, Tuskegee Institute was flooded with letters of sympathy. Carver was buried in the Tuskegee Institute cemetery near the grave of Booker T. Washington. On January 9, 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt paid tribute to Carver in an address before Congress. Later that year Roosevelt signed legislation making Carver's birthplace a national monument.

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born c. 1861, near Diamond Grove, MO; died January 5, 1943, in Tuskegee, AL; son of Mary (a slave on the farm of Moses Carver); father unknown, but believed to have died in an accident shortly after George's birth. Education: Iowa State University, B.S., 1894, M.S., 1896. Religion: Presbyterian.

AWARDS

Fellow of the British Royal Society for the Arts, 1916; Spingarn Medal from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), 1923; D.Sc. from Simpson College, 1928; Roosevelt Medal for distinguished service to science, 1939; D.Sc. from University of Rochester, 1941; Thomas A. Edison Foundation Award, 1942; inducted into Hall of Fame for Great Americans, 1973, and National Inventors Hall of Fame, 1990.

CAREER

Worked odd jobs throughout Missouri, Kansas, and Iowa while pursuing a basic high school education, 1877-1890; Iowa State University, Ames, IA, assistant botanist and director of college greenhouse, 1894-1896; Tuskegee Institute, Tuskegee, AL, head of agriculture department, 1896-1910, head of department of research, 1910-1943; founder of George Washington Carver Foundation and Carver Museum at Tuskegee Institute; researcher focusing on improving Southern agriculture through crop diversification and finding multiple uses for various crops; author of articles on agriculture.