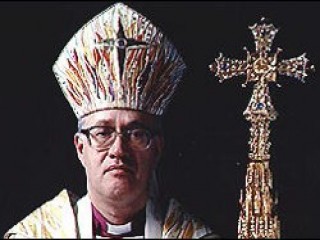

George Leonard Carey biography

Date of birth : 1935-11-13

Date of death : -

Birthplace : London, England

Nationality : English

Category : Arhitecture and Engineering

Last modified : 2011-05-17

Credited as : Archbishop of Canterbury, ,

The Right Reverend George Leonard Carey was formally enthroned as the 103rd Arch bishop of Canterbury in 1991. For the previous three years he had been Bishop of Bath and Wells, a region in southwest England.

Much of the world's religious community was surprised on July 25, 1990, when the announcement was made that Bishop George Carey would be the next Archbishop of Canterbury —head of the Church of England and symbolic leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. When Carey was formally enthroned in 1991, he took responsibility for 70 million people scattered across 164 countries.

For many generations, the Archbishop's throne has been occupied by men born into England's upper classes and educated in the country's most elite schools. Those responsible for selecting Carey (a man with humble beginnings) to lead the church, may have been motivated by their recognition that the Church of England was a deeply troubled institution, badly in need of fresh perspectives.

George Leonard Carey was born on November 13, 1935. He came from a working-class family in the East End of London, whose inhabitants are known as Cockneys. His father was a hospital porter, and the family lived in public housing. Carey said that he could remember having to share shoes with his brother. He left school at 15 and became an office clerk with the London Electricity Board. At 18 he was called up for national service in the Royal Air Force, where he was a radio operator. At that time he had a conversion experience and decided to offer himself for the ordained ministry.

He worked at home to secure entry to King's College, University of London. There he secured a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1962, and in that year he began to serve as curate (assistant) in the London evangelical parish of Islington. However, he also continued his academic studies. He was awarded a Master's degree in 1965 for a thesis on "Church, Ministry, Eucharist in the Apostolic Fathers" and, in 1971, a Doctorate for a thesis on "Church Order in the Shepherd of Hermas" (a second-century work).

This academic record led him to be appointed to the staff of three evangelical theological colleges: Oak Hill, London (1966-1970); St. John's Nottingham (1970-1975); and Trinity, Bristol (1982-1987), of which he was principal and where he had a profound effect in renewing the college. Meanwhile, from 1975 to 1982 he gained more parish experiences as vicar of St. Nicholas Durham. The city was a once-flourishing mining area in the north of England but was having a hard time when Carey came to the church. In 1988 he became Bishop of Bath and Wells.

His wife, Eileen, was a qualified nurse, and they had four children, two sons and two daughters. Carey was known to be a supporter of "green" issues, to be alert to the problems of inner-city parishes and urban renewal, and to be a lifelong supporter of the famous London Association Football (soccer) club, Arsenal.

In the modern world, all mainstream churches include a wide spectrum in understanding basic Christian beliefs, whether they acknowledge it or not. In the case of the Anglican Communion this has always been the case, because at the Reformation the Church of England took a conservative course in the conviction that the terms Protestant and Catholic were not antithetical but complementary. The term Protestant was understood as a protest in favor of a reformed Catholicism. However, in the Church of England there have always been those who emphasized one much more than the other, and this difference became sharper amid 19th-century controversies. Those on the Protestant side are usually referred to as Evangelicals and those on the Catholic side as Anglo-Catholics, but both also include a range of opinion within themselves. Together they represent, at the most, 40 percent of Anglicans; the remaining 60 percent or so are not and never have been of either party.

In recent years Evangelicals have gained ground while Anglo-Catholics have lost ground. This is largely because the new emphases in the Roman Catholic Church since the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) have undermined most of what they stood for.

The Anglican Communion is made up of 29 self-governing provinces. They are linked together by three entities:

the Lambeth Conference of bishops every ten years; informal occasional meetings of the primates of the provinces; and the Anglican Consultative Council, which meets every two or three years and is made up of two or three representatives, clerical and lay, of each province. All three entities are advisory, which means that the personal influence of the Archbishop of Canterbury, while not decisive, counts for a lot.

The present process in England of appointing archbishops and diocesan bishops begins with the Crown Appointments Commission. This is made up of eleven members drawn from the General Synod (bishops, other clergy, and laity), who serve for the five-year life of the synod, together with four representatives, clerical and lay, of the vacant diocese. They meet (with advisors) in an atmosphere of retreat and send two names in order of preference to the prime minister, who is normally expected to choose the preferred name to submit to the Queen of England for nomination. The process is entirely confidential.

The vacancy at Canterbury aroused a good deal of interest in the national media. Most of the leadership in the Church of England had clearly been far from happy with the general lines of policy and the general tone of the Thatcher administration since it came to power in 1979.

The population of the Anglican Communion is divided into 29 regional branches, and each branch has the authority to make its own rulings on the many controversies facing the modern church. Conflicting decisions on these issues, such as the ordination of women as priests, have already caused rifts between some of the member churches within the Anglican Communion. Other hotly debated issues within the Anglican Communion include the proper attitude toward homosexuality and the ordination of openly homosexual clergy, and the modernization of the liturgy.

Carey's appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury was significant for four reasons: First, at age 55, he could hope to have 15 years before retiring at 70, well past the next Lambeth Conference and long enough to exercise sustained influence. Second, his appointment marked a complete breakawayfrom the privileged backgrounds of the great majority of archbishops and bishops who have gone to public (U.S.A. "private") schools and then to the prestigious and wealthy ancient universities of Oxford and Cambridge. Third, Carey was an evangelical who was fairly conservative in his attitude to the Bible and to doctrine, but with a well-trained and open mind. In particular, he argued in speech and writing in favor of the ordination of women, against the evangelicals who said it was contrary to the Bible for women to have any authority over men. Several provinces of the Anglican Communion now ordain women, but so far in the Church of England the opposing minority has secured a blocking one-third vote. Carey's attitude may be of great importance when the issue is taken up again. Carey also had contacts with the charismatic Christian movement. Lastly, it seemed that Carey would be a "people's archbishop." He was a good communicator and had not lost touch with his roots. He said that the church was "light years away" from the kind of people among whom he grew up, and that instead of being a "Jesus movement" it had become identified with static church buildings.

While remaining a conservative theologian, Carey is involved with liberal social causes. As he told Maclean's, "Social and political issues are there, at the very heart of the Christian good news." His concern for suffering and his influence was made clear when, in 1994, he visited the Muslim country of Sudan, which suffered from civil-war and where Christians were persecuted. His desire to meet with only Christians there, not the government, was seen by the government as a snub. According to the National Catholic Reporter, "His visit has drawn attention to the persecution of Christians and the forgotten war in the southern Sudan."

Carey wrote eight books on such topics as Christology, ecumenism, relations with the Roman Catholic Church, and the existence of God. They are not of the long-lasting type and will not be easily obtainable. The best background reading is on Anglicanism as such. Here the Pelican Anglicanism by Stephen Neill is good (first published 1958). A series of 30 essays in The Study of Anglicanism, edited by Stephen Sykes and John Booty, an Anglo-American undertaking (S.P.C.K. and Fortress Press, 1988) covers almost every aspect. Nearly all the essays are good and some are outstanding. Further readings are also available in Maclean's (August 6, 1990); Newsweek (April 22, 1991); and National Catholic Reporter (January 14, 1994).