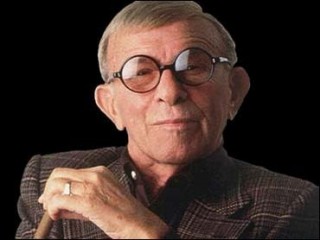

George Burns biography

Date of birth : 1896-01-20

Date of death : 1996-03-09

Birthplace : New York City, New York, US

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-05-24

Credited as : Actor comedian, cigar-in-hand comedy routines, writer

Comedian and actor George Burns is a show business legend. When he died at the age of 100 in 1996, he had spent 90 years as a comic entertainer, making numerous television and film appearances and earning an enduring popularity with his obligatory-cigar-in-hand comedy routines.

In his ninety years in show business, George Burns had time for three careers. His first two decades were spent as a small-time vaudeville performer. Later, as part of a comedy duo with his wife, Gracie Allen, he achieved wide popularity on the stage, radio, television, and in films. Finally, after Allen's death, Burns performed as a stand-up comedian and comic actor, winning an Academy Award at the age of 80.

George Burns was born Nathan Birnbaum on January 20, 1896, the ninth of twelve children of an Orthodox Jewish family. The Birnbaums, recent immigrants from Eastern Europe, lived on New York City's impoverished lower East Side. His father was a cantor (a painfully out-of-tune one, according to Burns's account), who worked as a last-minute substitute at various New York synagogues.

After his father's death, Burns began a career in show business at the age of seven. To help support the family, he formed the Pee Wee quartet, a group of child performers who sang and told jokes on street corners. He and his brothers also helped out by stealing coal from a nearby coal yard—earning the nickname the Burns Brothers. He would later settle on this as a stage name, changing his first name to George after an idolized older brother.

Burns's early performing years were spent doing whatever he could to earn money. In 1916, under the name Willy Delight, he performed as a trick roller-skater on the Keith Vaudeville Circuit. Later, as Pedro Lopez, he taught ballroom dancing. Over the years, he tried several other names—Billy Pierce, Captain Betts, Jed Jackson, Jimmy Malone, Buddy Lanks—appearing in a wide range of vaudeville acts with many different partners. "When I first started in vaudeville I was strictly small-time," he reminisced in his book, How to Live to be 100—or More. "I'd be lying if I said I was the worst act in the world; I wasn't that good."

By 1923, he was appearing at the Union Theatre as George Burns, comedian, when he met his future partner, Gracie Allen. Allen, ten years younger than Burns, came from a San Francisco show business family, and had also been performing since she was a child. However, by the early 1920s, she had given up her fledgling career in entertainment to train as a stenographer. Allen was accompanying a friend on a backstage visit at the theater when she was introduced to Burns. In tune with her scatterbrained image, she confused him with someone else, and called him by the wrong name for several days.

Burns and Allen made their performing debut in 1924. In his previous act, Burns was both the writer and the comedian, while his partner played the straight man. Burns initially stuck to this format in his act with Allen, but quickly learned that she was the funny one. "Even her straight lines got laughs," Burns was quoted as saying in The Guardian. "She had a very funny delivery …. they laughed at her straight lines and didn't laugh at my jokes."

Soon Burns and Allen developed the act that would make them famous: he played the bemused, cigar-smoking boyfriend and comic foil to her dizzy, muddled girlfriend. In a distracted, little-girl voice, Allen told rambling stories about her family, while Burns asked questions. "I just asked Gracie a question, and she kept talking for the next 37 years," he later recalled (quoted in The Daily Telegraph).

After performing together in vaudeville for three years, Burns and Allen were married in Cleveland on January 7, 1926. Theirs was a famously happy marriage. "I'm the brains and Gracie is everything else, especially to me," Burns once said (quoted in The Daily Mail). Later, they adopted two children, Sandra Jean and Ronald John.

Around the time of their marriage they were signed to a six-year contract with Keith theaters, which took them on tours of the United States and Europe. In 1930 Burns and Allen joined Eddie Cantor, George Jessel, and others in a headline bill marking the end of vaudeville at the Palace Theatre in New York. After this appearance, as well as appearances on the Rudy Vallee and Guy Lombardo shows, CBS signed the team for their own radio program.

The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show debuted on February 15, 1932. The team became famous for one exchange that ended that show, and every show. After a program filled with one non sequitur after another, Burns would say, long sufferingly, "Say goodnight, Gracie" and Allen would respond brightly, "Goodnight, Gracie."

During nineteen years in radio, Burns and Allen attracted an audience estimated at more than 45 million listeners. In 1940 their salary was reported to be $9,000 a week. Always modest about his role in the series, Burns claimed that Allen was solely responsible for their enduring success. "With Gracie, I had the easiest job of any straight man in history," he said (quoted in The Guardian). "I only had to know two lines—'How's your brother?' and 'Your brother did what?"'

Meanwhile, in 1931 they signed a contract with Paramount Studios to star in short films and, when not making pictures, to play on the stage of the Publix theaters. Their first full-length movie was The Big Broadcast of 1932. In addition to many short films, the team made an average of two films a year for Paramount. Their last film for Paramount was Honolulu (1939), which starred Eleanor Powell and Robert Young.

To attract attention for their radio show, Burns masterminded several publicity stunts. In 1933, Allen appeared on radio shows throughout the country, searching for her imaginary lost brother. The joke was so convincing that her real brother, an accountant in San Francisco, had to go into hiding until public interest in him had waned. During the 1940 election, Allen declared herself a nominee for the "Surprise Party," and campaigned on various radio shows, even holding a three-day convention in Omaha. She received several thousand write-in votes.

In October 1950, The Burns and Allen Show made the transition to television. The program used the same format as the successful radio program. The following exchange was typical of their humor: "Did the maid ever drop you on your head when you were a baby?" "Don't be silly, George. We couldn't afford a maid. My mother had to do it" (quoted in The Independent).

In 1958, angina forced Allen to retire—an event that merited the cover of Life magazine. At the time, The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show was then television's longest-running sitcom. Burns continued to perform in The George Burns Show, but the series only lasted one season. "The show had everything it needed to be successful, except Gracie," Burns recalled (quoted in The Independent).

Six years later, Allen died of cancer at the age of 59. Burns was devastated, and made almost daily visits to her grave. "The good things for me started with Gracie and for the next 38 years they only got better," he was quoted as saying in The Guardian. "But everything has a price. It still doesn't seem right that she went so young, and that I've been given so many years to spend without her."

After Allen's death, Burns devoted his time to McCadden, his television production company, which made such popular programs as The People's Choice (1955-58) and Mr. Ed (1961-66). Burns also appeared as a guest in various television specials throughout the sixties. However, his attempts to develop a new double act failed; he was unacceptable to the public with new partners like Carol Channing or Connie Stevens.

It was not until 1975 that Burns was given the opportunity to re-launch his performing career. After the death of Jack Benny, a contemporary and close friend from the vaudeville days, Burns took Benny's role opposite Walter Matthau in Neil Simon's film, The Sunshine Boys. The role of the ancient straight man, coming out of retirement for one last get-together with his shambling former partner, could not have been more perfect for Burns. At age 80, he won an Academy Award for best supporting actor—the oldest person to do so. "My last film was in 1939," he said at the time (quoted in The Daily Telegraph). "My agent didn't want me to suffer from over-exposure."

He followed his success with Oh God!, in which he played the deity wearing baggy pants, sneakers, and a golf cap. Two sequels followed, Oh God! II (1980) and Oh God! You Devil (1984), as well as several other comedies. None of these films was very successful, but Burns was undisturbed. "I just like to be working," he was quoted as saying in The Daily Telegraph.

Throughout the 1980s, Burns appeared often on television, hosting 100 Years of America's Popular Music (1981), George Burns and Other Sex Symbols (1982) and George Burns Celebrates 80 Years in Show Business (1983). By this time, his comic material, mostly one-liners, centered almost exclusively on his age and longevity.

Burns also published various books, including Dr. Burns' Prescription for Happiness (1985) and a tribute to his wife, Gracie, A Love Story (1988), in which he revealed that Allen was actually his second wife. During his vaudeville days, Burns had formed a dancing act with Hannah Siegel, whom he had rechristened Hermosa Jose, after his favorite cigar. When their act was booked for a 26-week tour, her parents refused to let her travel the country with Burns unless he married her. The marriage lasted as long as the tour, and then was dissolved.

Although Burns never remarried, during his 80s and 90s he developed an enthusiasm for taking out young women—which became another endless source for comic material. At 97, Burns was still writing, making stage appearances, and numbering Sharon Stone among his escorts.

Burns had planned shows to celebrate his 100th birthday at the London Palladium for January 20, 1996. However, after a bad fall in 1994, his health declined, and the performances were canceled. A few days before his 100th birthday, he was suffering from the flu, and was unable to attend a party in his honor. Burns died at his home in Los Angeles on March 9, 1996.