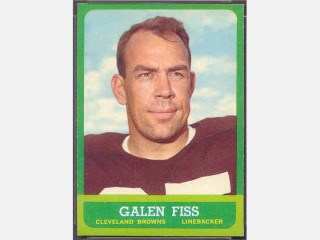

Galen Fiss biography

Date of birth : 1931-07-10

Date of death : 2006-07-20

Birthplace : Johnson, Kansas, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-09

Credited as : Football player NFL, played for the Cleveland Browns, Super Bowl

0 votes so far

The linebacker captained the 1964 squad to the NFL Championship, the last sports title won by a Cleveland team. Anyone who saw the game will never forget his age-defying, awe-inspiring performance, when he led a two-touchdown underdog to a 27-0 whitewash of John Unitas and the Baltimore Colts. His miraculous tackle of Lenny Moore, the game’s best open-field runner, is still the stuff of legend—a gentle irony for a man who neither sought nor received the type of adulation that comes with being a football icon.

Galen Royce Fiss was born on July 10, 1931, in Johnson, Kansas, a small town in the southwest part of the state. His family farmed the region’s hardscrabble land. Johnson was located in the Dust Bowl, and the Fiss clan was one of the few that did not follow the path west chronicled by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath. They stayed and coaxed wheat crops from the land, while also raising a few head of cattle to help make ends meet. Galen often spent 10 hours a day on the family tractor, working the farm with his father, grandfather and brother. When times improved, the Fiss family opened a garage in town, with Galen’s father serving as head mechanic and his uncle selling used cars and trucks.

Years of hard work gave Galen a rock-hard body to go with natural athletic ability and a relentless work ethic. He was the best football, baseball and basketball player for miles around, the star of Johnson High School. Galen figured he was just a big fish in a small pond, but when recruiter Don Fambrough from the University of Kansas offered a football scholarship, the Fiss family suspected greater things awaited the teenager.

They were correct. Galen would letter in all three sports in Lawrence, and draw national attention in football and baseball. In the summers, he returned to Johnson to help out with the farm, and also played for a top amateur baseball team out of Garden City, 90 minutes away.

Galen liked to hit people. He stood an even six feet and weighed just a shade over 200. The blows he delivered regularly separated runners from the ball, and occasionally their senses. He played linebacker and halfback for the Jayhawks, and was nicknamed the “Earthshaker” for his jarring tackles.

Galen’s hitting also earned him a spot on the Kansas baseball team. He was the starting catcher, and roomed with Dean Smith, a teammate on the baseball squad and along with Galen a member of the school’s freshman basketball team in 1949-50. Almost 40 years later, while sitting on KU’s athletic board of directors, Galen was instrumental in getting Smith’s protégé, Roy Williams, the coaching job after Larry Brown left the school.

The stars of the Jayhawk football squad, which was coached by J.V. Sikes, included halfback Wade Stinson and tackle Mike McCormack. The 1950 team finished 6-4 (3-3 in the Big 7). With a couple of breaks, Kansas could have gone 9-1. Galen played linebacker and running back, joining a stellar group of sophomores that included offensive linemen George Mrkonic and Oliver Spencer, plus Merlin Gish and Charlie Hoag. This group would fashion a 21-9 record in their three years together.

The 1951 Jayhawks went 8-2, relying on a high-powered offense to cover the 20 points a game they gave up on defense. The problem was not with the linebacking corps. Galen and Gish were among the best in the country. Galen also starred in a reserve role in the Kansas backfield. In a game against Kansas State, he scored his lone collegiate touchdown on an effort that saw him flatten five Wildcat tacklers. It was a classic “Galen Grinder,” as the fans liked to call his runs.

At season’s end, the Jayhawks earned a #20 national ranking. That was good enough to get them on the national TV schedule the following fall, as NBC broadcast their 13-0 pasting of TCU on September 20, 1952. It marked the first time a nationwide football audience saw the school play. The star of the '52 squad was Gil Reich, a great all-around player who had been banished from West Point for not reporting a case of cheating. He was one of the country’s best defensive backs, and also alternated with Jerry Robertson at quarterback. The Jayhawks posted a 7-3 mark and split their Big 7 meetings, but finished out of the Top 20. Galen earned All-Big 7 honors, not as a linebacker—where he anchored the team’s defense—but as a bruising fullback.

After the season, Galen was drafted by the Cleveland Browns in the 13th round, but he was not offered a contract. The Browns were the dominant team in pro football at the time, and Galen did not figure to make the squad. When the Cleveland Indians offered him a baseball contract, he decided to try his luck on the diamond. He played one year for their farm team in Fargo-Moorehad, which won the Northern League playoffs.

Galen split his time between catcher and outfield, and ended the year with a .275 average in 52 games. His manager that year was former All-Star Zeke Bonura. His teammates included an 18-year-old slugger named Roger Maris. The two remained friends for three decades.

After a two-year stint in the Air Force, during which he attained the rank of lieutenant, Galen received a $7,500 contract offer from the Browns. He was a married man now, and football money seemed a better bet than the $100 a week he would make in the minors. His salary would eventually rise to $25,000 a year in the mid 1960s. During his college and military career, he had bulked up to 230 pounds, and was now a formidable physical presence when he took the field.

Galen and his wife, Nancy, would be together for 51 years, and had three kids, Scott, Bob and Leslie. Galen informed the Indians that he would be playing football for a living from then on, and reported to his first NFL training camp in the summer of 1956. The Browns were coming off a 38-14 trouncing of the Detroit Lions in the Championship Game. Galen roomed with his old college teammate, Mike McCormack, who had joined the team two seasons earlier after completing his military service. In Galen's first few practices, when he took a beating and had trouble adapting to the team’s defensive system, it was McCormack who buoyed him by assuring him he was doing okay. If not for the future Hall of Famer’s presence, he might have quit camp and headed back home.

Galen was part of a linebacking unit that included future NFL coaches Walt Michaels and Chuck Noll. The first pro game he played for the Browns was the first he had ever seen—and the first he had played in three years.

Galen joined the Browns just in time to contribute to the first losing season in team history. (He intercepted one pass on the year.) Otto Graham had retired and his replacements, George Ratterman and Babe Parilli, were both felled by injuries. The upside of Cleveland’s 5-7 record was a high pick in the draft, which Cleveland used to select running back Jim Brown.

The Syracuse star was a key block in Paul Brown’s rebuilding program, which would include defensive lineman Paul Wiggin, linebacker Vince Costello, quarterback Milt Plum, running back Bobby Mitchell, guard Gene Hickerson, defensive back Jim Shofner, and Galen, who quickly became a team leader. Brown blended their skills with veterans like McCormack, Michaels, Lou Groza, Don Colo and Don Paul to record winning seasons for the rest of the decade.

The infusion of new blood paid dividends quickly, as the Browns returned to prominence in the Eastern Division, finishing 9-2-1. Brown was bigger than most linebackers and faster than most defensive backs, and NFL defenses had no idea how to stop him. He rolled up a league-high 942 yards, while Plum and Tom O’Connell connected on enough passes to keep opponents honest.

The Cleveland defense was the league’s stingiest. The Browns limited opponents to just 172 points in 12 games, recording two shutouts in the process. Galen emerged as one of the league’s best linebackers, permanently supplanting Noll on the right side.

The NFL title game pitted the Browns against the Lions. in Detroit. Written off after coach Buddy Parker quit and quarterback Bobby Layne broke his leg, the Lions proved their resilience by tying the San Francisco 49ers in the West and defeating them in a playoff. They carried this momentum into their meeting with the Browns and humiliated them 59-14.

The Browns finished 9-3 in 1958, but failed to win the East. They lost to the Giants on the last day of the season to finish in a tie, then lost the playoff a week later when New York held Brown to a mere eight yards in a 10-0 victory.

The Giants killed Cleveland’s 1959 season, too. After two heart-breaking losses in November, the Browns were beaten 48-7 by New York in the worst defeat in franchise history. They finished 7-5, in second place behind the Giants. In 1960, the Browns avenged this lost by crushing New York 48-34 on the last day of the season. Unfortunately, the Philadelphia Eagles finished ahead of both, and went on to claim the NFL Championship.

After missing the playoffs three years in a row, the finger-pointing started, and much of it was directed at coach Brown. Perhaps because the rival AFL was throwing money around, NFL players were starting to bristle at the hard-edged discipline of old-time coaches. Brown’s coaching methods were also coming under increased scrutiny as Cleveland faded from contention late in the 1961 season. Had the team played better against opposing passers, the Browns might have squeezed past the Giants and Eagles for the division title, but instead they finished third with a record of 8-5-1.

One of the best things the Browns did in 1961 was naming Galen team captain. Through all the ups and downs, he had proved to be utterly unflappable. He always did the right thing on and off the field, and always knew the right thing to say, regardless of a situation’s complexity. Not surprisingly, Galen was well-liked by everyone on the Browns, and well-respected—the perfect Gibraltar for a team in transition and turmoil.

With new owner Art Modell breathing down his neck, Brown decided to start retooling the club for the 1960s. His boldest move was the trade of Mitchell to the Redskins for Ernie Davis, the first African-American to win the Heisman Trophy, and the first black player to be signed by Washington. The promise of football’s ultimate two-man backfield collapsed that summer when Davis fell ill while working out with the college All-Stars. He was diagnosed with leukemia and never played a down for Cleveland, passing away the following spring.

Young Charlie Scales ended up getting most of the starts alongside Brown in 1962, resulting in a sub-1,000-yard campaign for the superstar. Once again, Cleveland fell short of the playoffs, finishing 7-6-1, behind the Giants and Pittsburgh Steelers. The lone bright spot was the emergence of newcomer Frank Ryan, a former Los Angeles Rams benchwarmer who seized control of the quarterback job after Plum was traded to the Lions and Len Dawson went to the AFL Dallas Texans. Galen recorded a career-high four interceptions, leading a corps that now included young Mike Lucci. Despite being a half-step slower, Galen was two steps smarter, and made the Pro Bowl for the first time. He also gained Second Team All-Pro recognition from two of the news services—the one and only time he would earn this honor.

At season’s end, Modell canned Brown, and ordered Cleveland's Brownie logo to be abandoned in an attempt to make a clean break with the past. Under new coach Blanton Collier, the Browns recaptured some of the old magic and finished 10-4 in 1963. Ernie Green became the starting halfback and was good enough to keep defenses honest against Brown, who reached the 1,000-yard mark in the team’s eighth game. He finished with a record 1,863 yards, while Ryan threw 25 TD passes—including 13 to Gary Collins, a second-year end out of Maryland. The Browns kept pace with the Giants until the 13th week, when they were ambushed by the Lions 38-10. The Giants wound up with 11 victories to deny the Browns the division crown once again. Galen was named to his second Pro Bowl after the season.

The Browns went into 1964 feeling they were just a couple of players away from putting a championship team on the field. They were right. They gave Ryan a second target by drafting Paul Warfield, and blocked flawlessly for Brown and Green all season long. On defense, the acquisition of Giants nemesis Dick Modzelewski made the Browns a great run-stopping team. Their Achilles heel was, as usual, the pass defense.

The collapse of the Giants in '64 opened the door for a new division winner, and the Browns established themselves early as the team to beat. As the campaign unfolded, the St. Louis Cardinals proved their only obstacle, tying the Browns in their first meeting and beating them in their second. Cleveland finished 10-3-1, a half-game better than the Cards. Galen played most of December with a cast from his fingers to his elbow after breaking his left thumb. League rules demanded that he wrap the cast with a thick sponge, which the referees inspected each game before he was allowed to play.

The Browns specialized in winning ugly. Their defense gave up the most first downs in the league, the second most rushing yards, and the third most passing yards. The team played a zone defense in order to cover deficiencies in their defensive backfield, which was the NFL’s slowest.

Baltimore, the winner in the west, by contrast, led the NFL in points scored and fewest points allowed. The Colts were picked to win the championship by almost all of the experts, with some bookies listing them as two-touchdown favorites. This puzzled Galen, who knew Baltimore had a great team, but felt that the talent and chemistry of his Browns gave them an advantage, particularly since the game would be played in Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium.

As the team captain, Galen had the honor of walking to midfield to confer with officials before the game. He had never heard the stadium louder before kickoff.

Galen got the crowd of 79,544 going in the second quarter when he made a brilliant tackle on a swing pass from John Unitas to Lenny Moore. Moore had lined up as a pass blocker, and the entire Cleveland defense bought it. When Unitas whirled around and fired a pass to him, he saw only one defensive player between himself and the goal line, some 70 yards away—Galen Fiss.

Galen knew instantly he was out of position. His job on this play was to stay close to the line and protect against screen passes, so he could tackle the receiver before the blocking set up. On this play, he was way too deep. All-Pros Jim Parker and Bob Vogel were steaming toward him, and there was no one to back him up. Galen had no choice but to attack the play. He zig-zagged between Parker and Vogel and cut a shocked Moore’s legs out with a diving ankle tackle just as he turned the corner. Whenever they met in the ensuing years, Moore asked Galen how he got to him on that play.

It is no exaggeration to characterize this as a momentum-turning hit. The play kept the score at 0-0, and many of Galen’s teammates said that was the moment they were convinced they could beat the Colts.

By this point, the Cleveland fans had begun to notice something different about their team’s defense sets. Gone was the zone, replaced by a tight man defense. Coach Collier felt the key to stopping Unitas was keeping receivers Ray Berry and Jimmy Orr from running crossing patterns into the seams behind the linebackers. Galen spent much of the day chasing Berry with help from Walter Beach, while Jim Houston and Ross Fitchner shadowed Orr. The move surprised the Colts, who were never able to adjust.

After a scoreless first half, the Browns struck in the third quarter with a Lou Groza field goal and a pair of TD passes from Ryan to Collins. The Colts had focused their pass coverage on the speedy Warfield, and paid the price again in the fourth quarter when Collins made his third touchdown grab to turn the championship game into a 27-0 rout. The big story was Cleveland’s defensive effort against the powerhouse Colts, who managed a mere 177 yards on offense—all this against a supposedly porous unit. One of the many unsung heroes was lineman Jim Kanicki, who got the better of Parker all day.

To his surprise, Galen was singled out for special praise. It was said that he played the “perfect” game. Over the years, he denied it, but his performance transformed him into a Cleveland cult hero. Actually, Galen did turn in one of the best championship efforts by an NFL linebacker. There were 11 Hall of Famers on the field that day, but none was better than the Cleveland captain. He harassed Unitas all game lone, sacking him once and clubbing him in the helmet with his cast on another play. When Galen dropped into coverage, he was thinking right along with the Baltimore quarterback, blanketing Berry on his precision routes and taking away one of Baltimore’s most formidable weapons. He tipped one pass that was picked off by Vince Costello. Galen could easily have been named MVP. Instead, Collins, who caught three TD passes, was accorded that honor.

Teammate Paul Wiggin once said that Galen turned in “the most beautifully played game I’ve ever seen by one individual.” Jim Brown called Galen’s tackle of Moore “one of the most inspirational plays in the history of football.”

In 1965, when Galen received his NFL Championship ring, it did not fit on his gnarled right ring finger. That meant he would have to wear it on his left hand—in place of his wedding ring. Nancy understood.

That season, the Browns successfully defended their Eastern title, and returned to the championship game, against the Green Bay Packers. This time there would be something more than the NFL title on the line—the winner would advance to the very first Super Bowl, against the AFL champion.

The two teams met not on the frozen tundra for which Lambeau Field was so famous, but in a muddy quagmire. The Browns led 9-7 after one quarter, but the Packer running attack slowly wore them down. Paul Hornung and Jim Taylor combined for more than 200 yards in a 23-12 victory.

The 1966 season marked Galen’s last. He was 36 and slow of foot, but he and the Browns still had a great year, recovering from an 0-2 start to post nine victories. That was not enough, however, to hold off the fast-improving Cowboys, who won 10 times.

When he hung up the pads for the last time, Galen had played 11 NFL seasons and missed only five games. After retiring, he settled in Kansas City and got into the insurance business with McCormack, his longtime friend and teammate. Galen ran his own agency for 20 years. His sons—both of whom played football at his alma mater—still run the company, G.R. Fiss Co., today. Galen developed Alzheimer’s and died on July 20, 2006. He was 75.

Galen Fiss was sometimes asked if he minded being remembered by so many football fans for one play—the Moore tackle in the 1964 title game.

His answer spoke volumes about him as a player and a person. “It’s an honor,” he said, “to be remembered at all.”