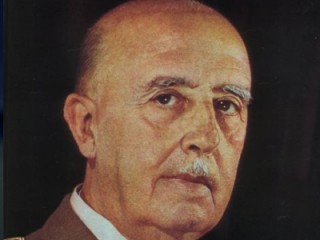

Francisco Franco biography

Date of birth : 1892-12-04

Date of death : 1975-11-20

Birthplace : El Ferrol, Galicia, Spain

Nationality : Spanish

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2011-04-28

Credited as : general and dictator, Spanish Civil War, head of State 1939

The Spanish general and dictator Francisco Franco played a major role in the Spanish Civil War and became head of state of Spain in 1939.

Born at El Ferrol, a town in the northeastern Spanish province of Galicia, on December 4, 1892, Francisco Franco was the second of five children born to Maria del Pilar Bahamonde y Pardo de Andrade and Don Nicolas Franco, who had continued the Franco family tradition by serving in the Naval Administrative Corp. The young Franco was rather active; he swam, went hunting, and played football. At 12, he was admitted to the Naval Preparatory Academy whose graduates were destined for the Spanish navy. However, international events conspired to cut short his anticipated naval career. In 1898, much of the navy had been sunk by the United States in the Spanish-American War. Spain was slow to rebuild, therefore many ports which had relied on naval contracts were plunged into an economic recession. El Ferrol was hit hard, and entrance examinations for the navy were cancelled, but not before Franco passed for entrance to the Toledo Infrantry Academy in 1907. Franco inherited the nicknames "Franquito" or "Frankie Boy," since he would not participate in the same activities as his fellow students. He became the object of malicious bullying and initiations, and graduated in the middle of his class in 1910. Until 1912, Franco served as a second lieutenant. He was first posted to El Ferrol but in 1912 saw service in Spanish Morocco, where Spain had become involved in a stubborn colonial war. By 1915, at age 22, he had become the youngest captain in the Spanish army. In 1916, he was severely wounded while leading a charge. He was decorated, promoted to major and transferred to Oviedo, Spain. During the next three years, he romanced Carmen Polo y Martinez Valdes, and delayed his plans for the Spanish Foreign Legion for marriage until 1923. Franco became commander in 1922 and rose to the rank of brigadier general (at the age of 33) by war's end in 1926.

During the next few years, Franco commanded the prestigious General Military Academy in Saragossa. In 1928 a daughter, Carmen, his only child, was born. He maintained friendships with the dictator, Miguel Primo de Rivera, and King Alfonso XIII, but when both were overthrown and the Second Republic began a radical reconstruction of Spanish society, Franco surprisingly remained neutral and avoided military conspiracies.

Military governorships in Corunna and the Balearic Islands were followed by promotion to major general in reward for his neutrality, but with the advent of a more conservative Cabinet Franco commanded the Foreign Legion in the suppression of the Asturias revolt (October 1934). Now identified with the right, in 1935 he was made commander in chief of the army.

In February 1936 the leftist government of the Spanish republic exiled Franco to an obscure command in the Canary Islands. The following July he joined other right-wing officers in a revolt against the republic which is when the Spanish Civil War began. In October they made him commander in chief and head of state of their new Nationalist regime. During the three years of the ensuing civil war against the republic, Franco proved an unimaginative but careful and competent leader, whose forces advanced slowly but steadily to complete victory on April 1, 1939. On July 18 Franco pronounced in the Nationalists' favor and was flown to Tetuán, Spanish Morocco. Shortly afterward he led the army into Spain. The tide was already turning against the Republicans (or Loyalists), and Franco was able to move steadily northward toward Madrid, becoming, on September 29, generalissimo of the rebel forces and head of state.

Franco kept Spain out of World War II, but after the Axis defeat he was labeled the "last of the Fascist dictators" and ostracized by the United Nations. Strong connections with the Axis powers and the use of the fascist Falange ("Phalanx") organization as an official party soon identified Franco's Spain as a typical antidemocratic state of the 1930s, but El Caudillo (the leader) himself insisted his regime represented the monarchy and the Church. This attracted a wide coalition linked to Franco, who, with the death of General Sanjurjo in 1936 and General Mola the next year, remained the only Nationalist leader of importance. By the end of the Civil War in March 1939, he ruled a victorious movement which was nevertheless hopelessly divided among Carlists, Requetes, monarchists, Falangists, and the army. Foreign opposition to Franco decreased and in 1953 the signing of a military assistance pact with the United States marked the return of Spain to international society.

The need to avoid immediate Axis involvement in order to begin recovery temporarily maintained the tenuous coalition. Franco's statement, "War was my job; I was sure of that," showed his hesitant attitude toward the prospect of civilian statecraft. Yet he maneuvered with finesse through World War II, beginning with his famous rebuff of Hitler at Hendaye on October 23, 1940.

Except for sending the Blue Division to the Russian front, Franco resisted paying off his obligations to Germany and Italy. Instead he allied with Antonio Salazar, the Portuguese dictator, who counseled neutrality. Negotiations with the United States solidified this stand, and in October 1943 relations with the Axis powers were broken. But Allied antagonism was only somewhat mollified by this belated effort, and on December 13, 1946, the United Nations recommended diplomatic isolation of Spain.

Franco met this new threat by dismissing Serrano Suner from office, removing the overtly fascist content from the Falange, and limiting all factional political activity. In 1946 the newly created United Nations declared that all countries should remove their ambassadors from Madrid. He also issued a constitution in 1947 which declared Spain to be a monarchy with himself as head of state possessing the power to name his successor. This successor might be either king or regent, thus leaving the future unresolved, a tactic which Franco capitalized on throughout most of the post-war period to prevent any group or individual from making strong claims upon his government. Cabinet ministers were chosen with an eye to national balance, and so slowly Spain moved away from sectarianism.

The economic and diplomatic situation remained difficult. In 1948 France closed its border with Spain, and exile groups, sometimes supported by the U.S.S.R., maintained extensive propaganda campaigns. Flying the banner of anti-communism during the emerging Cold War served him well. In 1950, the United States returned its ambassador and three years later the Americans were allowed four military bases in Spain. President Dwight D. Eisenhower personally greeted Franco in Madrid in 1959. Indeed, considering his Concordat with the pope in 1953, Franco can be said to "have arrived." Franco's regime became somewhat more liberal during the 1950s and 1960s. It depended for support not on the Falange, renamed the National Movement. Almost as if this signaled the end of isolation, tourist trade began picking up until within a few short years Spain had a substantial surplus in international payments. Spain enjoyed rapid economic growth in the 1960s and by the end of the century, its previously agricultural economy had been industrialized.

This upsurge permitted Franco to engage in a slow process of modernization that contained a few liberal elements. In May 1958 he issued the principles of the National movement, which contained a new series of fundamental freedoms still dominated, however, by an absolute prohibition on political opposition or criticism of the government. On several later occasions control of the press was temporarily relaxed, and in 1966 the Cortes, up to then a purely appointive body, was made partially elective.

In matters of economic planning, however, Franco demonstrated more consistent liberal intent. He led a belated industrial recovery that raised the standard of living and decreased social unrest. Many of his later Cabinet technocrats, however, were members of Opus Dei, a relatively unknown Catholic laymen's organization reputed to have enormous economic power. Franco's reliance upon this group became obvious in 1969, when the Falange lost its official status.

Franco's health declined during the 1960s. In 1969 he designated Prince Juan Carlos, grandson of Spain's former king, Alfanso XIII, as his official successor. In 1973 Franco relinquished his position as premier but continued to be head of state. Such was the character of Franco's regime that the choice was rumored to have been made by the army, still the most important institution in Spanish society. In July 1974, Franco suffered an attack of thrombophlebitis, an attack that signaled a host of successive afflictions over the following 16 months: partial kidney failure, bronchial pneumonia, coagulated blood in his pharynx, pulmonary edema, bacterial peritonitis, gastric hemorrhage, endotoxic shock and finally, cardiac arrest. At one point, Franco exclaimed, "My God, what a struggle it is to die." On November 20, 1975, when relatives asked doctors to remove his support systems, the 82-year-old Franco passed away. After Franco's death in Madrid, Juan Carlos became king.