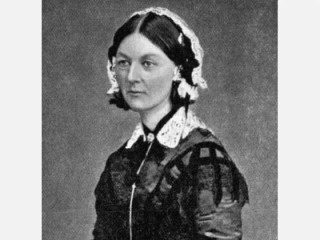

Florence Nightingale biography

Date of birth : 1820-05-12

Date of death : 1910-08-13

Birthplace : Florence, Italy

Nationality : British

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2010-08-27

Credited as : Nurse, mathematician and statistician,

13 votes so far

Early Life

Born into a wealthy and well-connected British family at the ‘Villa Colombaia’ in Florence, Italy, she was named after the city of her birth, as was her older sister (named Parthenope for the old city that is now Naples). A brilliant and strong-willed woman, Florence rebelled against the expected role for a woman of her status, which was to become an obedient wife.

Inspired by what she understood to be a divine calling (first experienced in 1837 at the age of 17 at Embley Park and later throughout her life), Nightingale made a commitment to nursing, a career with a poor reputation and filled mostly by poorer women. Traditionally, the role of nurse was handled by female “hangers-on” who followed the armies; they were equally likely to function as cooks or prostitutes. Nightingale was particularly concerned with the appalling conditions of medical care for the legions of the poor and indigent. She announced her decision to her family in 1845, evoking intense anger and distress from her family, particularly her mother.

In December 1844, in response to a pauper’s death in a workhouse infirmary in London that became a public scandal, Nightingale became the leading advocate for improved medical care in the infirmaries and immediately engaged the support of Charles Villiers, then president of the Poor Law Board. This led to her active role in the reform of the Poor Laws, extending far beyond the provision of medical care.

In 1846 she visited Kaiserwerth, a pioneering hospital established and managed by an order of Catholic sisters in Germany, and was greatly impressed by the quality of medical care and by the commitment and practises of the sisters.

Rejection of marriage proposal

In 1851 she rejected the marriage proposal of politician and poet Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton, against her mother’s wishes. Convinced that marriage would interfere with her ability to follow her calling to nursing, Nightingale continued to reject his proposal.

When in Rome in 1847, recovering from a mental breakdown precipitated by a continuing crisis of her relationship with Milnes, Nightingale met Sidney Herbert, a brilliant politician who had been Secretary at War (1845 – 46), a position he would hold again (1852 – 1854) during the Crimean War. Herbert was already married but he and Nightingale were immediately attracted to each other and they became life-long close friends. Herbert was instrumental in facilitating Nightingale’s pioneering work in Crimea and in the field of nursing, and Nightingale became a key advisor to Herbert in his political career.

Her career began at Kaiserwerth

Florence Nightingale’s career in nursing began in earnest in 1851 when she received four months’ training in Germany as a deaconess of Kaiserwerth. She undertook the training over strenuous family objections concerning the risks and social implications of such activity, and the Catholic foundations of the hospital. While at Kaiserwerth, Florence reported having her most important intense and compelling experience of her divine calling.

On August 12, 1853, Nightingale took a post of superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Upper Harley Street, London, a position she held until October 1854. Her father had given her an annual income of £500 (roughly $50,000 in present terms) that allowed her to live comfortably and to pursue her career.

Her most famous contribution was during the Crimean War, which became her central focus when reports began to filter back to Britain about the horrific conditions for the wounded. On October 21, 1854, Nightingale and a staff of 38 women volunteer nurses, trained by Nightingale and including her aunt Mai Smith, were sent to the Crimea, with the authorisation of Sidney Herbert.

The hospital in Scutari

She arrived early in November 1854. In Scutari (modern-day Uskudar in Istanbul, Turkey) Nightingale and her nurses found wounded soldiers being badly cared for by overworked medical staff in the face of official indifference. Medicines were in short supply, hygiene was being neglected, and mass infections were common, many of them fatal. There was no equipment to process food for the patients.

Nightingale and her compatriots began by thoroughly cleaning the hospital and equipment, and reorganizing patient care. Although she met resistance from the doctors and officers, her changes vastly improved conditions for the wounded and by April dropped mortality rates by 40 per cent to just two per cent.

She sent many letters to Herbert, to facilitate better medical care.

When she first arrived in the Crimea, she travelled on horseback making the inspections, she then transferred to a mule cart, and was reported to have escaped serious injury when it was toppled in an accident. Following this episode she used a solid Russian-built carriage, with waterproof hood and curtains. The carriage was returned to England after the war and subsequently given to the Nightingale training school for nurses, which she founded at St Thomas’s hospital. The carriage was damaged when the hospital was bombed in the Blitz. It was restored and transferred to the Army Museum in Aldershot.

Reportedly she treated 2,000 patients herself. She also contracted Crimean Fever. She is remembered today because of the compassion, care and administrative skills that she introduced to the profession of nursing, to patient care and to the maintenance of medical records.

Nightingale’s work inspired massive public support throughout England, where she was celebrated and admired as “The Lady with the Lamp” after the Grecian lamp she always carried in her tireless evening and night-time visits to injured soldiers. Nightingale’s lamp also allowed her to work late every night, maintaining meticulous medical records for the hospital, and writing personal letters to the family of every soldier who died in the hospital. The depth of her commitment to the care of her patients in Crimea earned her the everlasting respect and affection of the common soldier.

Heroic return home

Nightingale returned to Britain a heroine on August 7, 1857, and, according to the BBC, was arguably the most famous Victorian after Queen Victoria herself .

Florence moved from her family home in Middle Claydon, Buckinghamshire to the Burlington Hotel in Piccadilly. However, she was stricken by a fever of possible psychosomatic origin, in part a delayed response to the stress of her work in the Crimean War and her bout with Crimean fever. She barred her mother and sister from her room and rarely left it. It has been suggested that she may have suffered from bipolar disorder or myalgic encephalitis . See CBC story: ‘Florence Nightingale suffered from bipolar disorder’

In response to an invitation from Queen Victoria, and despite the limitations of confinement to her room, Florence Nightingale played the central role in the establishment of the Royal Commission on the Health of the Army, of which Sidney Herbert became chairman. As a woman, Nightingale could not be appointed to the Royal Commission, but she wrote the Commission’s 1,000-plus page detailed report that included detailed statistical reports and was instrumental in the implementation of its recommendations.

Army Medical School

The report of the Royal Commission led to a major overhaul of army military care, and to the establishment of an Army Medical School and of a comprehensive system of army medical records.

On November 29, 1855, a public meeting to give recognition to Florence for her work in the Crimea led to the establishment of the Nightingale Fund, to raise funds for training of nurses and there was an outpouring of generous donations. Sidney Herbert served as the honorary secretary of the fund, and the Duke of Cambridge was chairman.

By 1859, Florence had £45,000 at her disposal from the Nightingale Fund to set up the Nightingale Training School (now called the Nightingale School of Nursing) at St Thomas’ Hospital on July 9, 1860. The first trained Nightingale nurses began work on May 16 at the Liverpool Workhouse Infirmary. She also campaigned and raised funds for the Royal Buckinghamshire Hospital in Aylesbury, near her family home.

Florence Nightingale wrote Notes on Nursing which was published in 1860, a slim 136-page book that served as the cornerstone of the curriculum at the Nightingale School and other nursing schools established. Notes on Nursing also sold well to the general reading public and is considered as a classic introduction to nursing.

Nightingale spent the rest of her life promoting the establishment and development of the nursing profession and organizing it into its modern form.

Nightingale Fund nurses

By 1882 Nightingale nurses had a growing influential presence in the embryonic nursing profession, and some had become matrons at several leading hospitals, including, in London, St Mary’s Hospital, Westminster Hospital, St Marylebone Workhouse Infirmary and the Royal Hospital for Incurables at Putney; and throughout Britain, e.g. Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley; Edinburgh Royal Infirmary; Cumberland Infirmary; Liverpool Royal Infirmary as well as at Sydney Hospital, in New South Wales, Australia.

After the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, Nightingale’s work served as an inspiration for nurses in the war, and Union government approached her for advice to organise field medicine. Although her ideas met official resistance they inspired the volunteer body of United States Sanitary Commission and US volunteers like Dorothea Dix, Clara Barton and Cornelia Hancock.

In 1869 she returned to England and, with Elizabeth Blackwell, opened the Women’s Medical College.

Mathematician & statistician

Nightingale had exhibited a gift for mathematics from an early age, and excelled in the subject under the tutorship of her father. She had a special interest in statistics, a field in which her father was an expert, and was a pioneer in the nascent field of epidemiology. Florence made extensive use of statistical analysis in the compilation, analysis and presentation of statistics on medical care and public health.

In her later life, she made a comprehensive statistical study of sanitation in Indian rural life and was the leading figure in the introduction of improved medical care and public health service in India. See Florence Nightingale, the passionate statistician and Biography of Nightingale at MacTutor History of Mathematics.

She invented a diagram she called the coxcomb or polar area chart-similar to today’s pie chart-to depict changing patient outcomes in the military field hospital she managed. She made extensive use of the coxcomb to present reports on the nature and magnitude of the conditions of medical care in the Crimean War to Members of Parliament and civil servants who would have been unlikely to read or understand traditional statistical reports. As such, she was a pioneer in the visual presentation of information, now pioneered by Edward Tufte, and has earned high respect in the field of information ecology. See Polar area chart, or coxcomb, diagram.

In 1858, Florence Nightingale was elected the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society and she later became an honorary member of the American Statistical Association.

Royal recognition

In 1883 Queen Victoria awarded Florence Nightingale with the Royal Red Cross and in 1907 she became the first woman to be awarded the Order of Merit. In 1908 she was given the Honorary Freedom of the City of London. She could not leave her bed after 1896 and died on August 13, 1910. The offer of burial in Westminster Abbey was declined by her relatives, and she is buried in the graveyard at St. Margaret Church in East Wellow, England.

Florence Nightingale’s lasting contribution has been her role in founding the nursing profession, and in the shining example she set for nurses throughout the profession of commitment to patient care and hospital administration. There is a Florence Nightingale Museum in London.

There are countless examples of Florence Nightingale’s continuing legacy in the nursing profession that she founded, from the continuing work of the Nightingale School of Nursing and throughout the entire field of nursing education and medical records.

Today, there are three hospitals in Istanbul named after her: F. N. Hastanesi in Sisli, (the biggest private hospital in Turkey), Metropolitan F.N. Hastanesi in Gayrettepe and Avrupa F.N. Hastanesi in Mecidiyekoy, all belonging to the Turkish Cardiology Foundation.

During the Vietnam War, Florence Nightingale served as an inspiration for many US Army nurses and sparked a continuing renewal of interest in her life and work, that, inter alia, caught the attention of Country Joe of Country Joe and the Fish who has assembled an extensive web site in her honor.

The Agostino Gemelli Medical Centre in Rome, the first University-based hospital in Italy and one of its most respected medical centers, is the research and teaching hospital of Universita Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Catholic University of the Sacred Heart). It honored Florence Nightingale’s contribution to the nursing profession by giving the name Bedside Florence to a wireless ward system they have developed that equips nurses with Compaq iPAQ hand-held computers connected to a Windows 2000 wireless network .