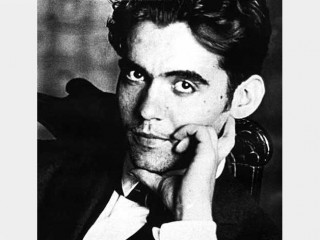

Federico Garcia biography

Date of birth : 1898-06-05

Date of death : 1936-08-19

Birthplace : Fuentevaqueros, Granada, Spain

Nationality : Spanish

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-08-23

Credited as : Writer and artist, ,

0 votes so far

Federico Garcia Lorc a was "a child of genius beyond question," declared Jorge Guillen in Language and Poetry. A Spanish poet and dramatist, Garcia Lorca was at the height of his fame in 1936 when he was executed by fascist rebels at the age of thirty-eight; in the years thereafter, Guillen suggested, the writer's prominence in European culture matched that of his countryman Pablo Picasso. Garcia Lorca's work has been treasured by a broad spectrum of the reading public throughout the world; his complete works have been reprinted in Spain almost every year since the 1950s, and it has been argued that he remains more widely recognized in the English-speaking world than any Spanish writer except Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote. According to Andrew A. Anderson in Gay and Lesbian Biography, "Garcia Lorca ranks as Spain's most famous twentieth-century author."

Garcia Lorca was familiar with the artistic innovators of his time, and his work shares with theirs a sense of sophistication, awareness of human psychology, and overall pessimism. But while his contemporaries often preferred to appeal to the intellect, Garcia Lorca gained wide popularity by addressing basic human emotions. He possessed an engaging personality and a dynamic speaking style, and he imbued his writing with a wide range of human feeling, including awe, lust, nostalgia, and despair. "Those who knew him," wrote his brother Francisco in a foreword to Three Tragedies, "will not forget his gift . . . of enlivening things by his presence, of making them more intense." The public image of Garcia Lorca has varied greatly since he became famous in the 1920s. Known primarily for works about peasants and gypsies, he was quickly labeled a simple poet of rural life--an image he felt oversimplified his art. His death enraged democratic and socialist intellectuals, who called him a political martyr; but while Garcia Lorca sympathized with leftist causes, he avoided direct involvement in politics. In the years since his death, his literary biographers have grown more sophisticated, revealing his complexity both as a person and as an artist.

To biographer Carl Cobb, Garcia Lorca's "life and his work" display a "basic duality." Despite friends and fame Garcia Lorca struggled with depression, concerned that his homosexuality, which he hid from the public, condemned him to live as a social outcast. While deeply attached to Spain and its rural life, he came to reject his country's social conservatism, which disdained his sexuality. Arguably, Garcia Lorca's popularity grew from his conscious effort to transform his personal concerns into comments on life in general, allowing him to reach a wide audience. During his youth Garcia Lorca experienced both Spain's traditional rural life and its entry into the modern world.

Born in 1898, he grew up in a village in Andalusia--the southernmost region of Spain, then largely untouched by the modern world. Such areas were generally dominated by the traditional powers of Spanish society, including the Catholic church and affluent landowners. Garcia Lorca's father, a landowning liberal, confounded his wealthy peers by marrying a village schoolteacher and by paying his workers generously. Though Garcia Lorca was a privileged child, he knew his home village well, attending school with its children, observing its poverty, and absorbing the vivid speech and folktales of its peasants. "I have a huge storehouse of childhood recollections in which I can hear the people speaking," Garcia Lorca was quoted as stating by biographer Ian Gibson. "This is poetic memory, and I trust it implicitly." Speaking of Garcia Lorca's childhood, Arnold Weinstein explained in European Writers: "As a child in Granada, Lorca entertained his family with imitations of the best show in town: the Mass. He would conscript his younger brother and sisters into the production by having them perform the roles of acolytes and confessors. The maid was his costume designer. His father, a cigar-smoking, macho farmer, spent long days on horseback overseeing his vast Andalusian holdings. His mother, a former schoolteacher, spent endless hours with Federico, who needed special care because of an infantile affliction (probably poliomyelitis) that left him weak for years to come."

The Family Moves

Once Garcia Lorca moved with his parents to the Andalusian city of Granada in 1909, many forces propelled him into the modern world. Spain was undergoing a lengthy crisis of confidence, spurred by the country's defeat by the United States in the War of 1898. Some Spaniards wished to strengthen traditional values and revive past glory, but others hoped their country would moderate its conservatism, foster intellectual inquiry, and learn from more modernized countries. With his parents' encouragement Garcia Lorca encountered Spain's progressives through his schooling, first at an innovative, nonreligious secondary school, and then at the University of Granada, where he became a protege of such intellectual reformers as Fernando de los Rios and Martin Dominguez Berrueta. By his late teens Garcia Lorca was already known as a multi-talented artist--his first book, the travelogue Impresiones y paisajes (Impressions and Landscapes), appeared before he was twenty--but he was also a poor student. Skilled as a pianist and singer, he would probably have become a musician if his parents had not compelled him to stay in school and study law. "I am a great Romantic," Gibson quoted him as writing to a friend at the time. "In a century of Zeppelins and idiotic deaths, I weep at my piano dreaming of the Handelian mist."

In 1919 Garcia Lorca transfered to the University of Madrid, where he ignored classes in favor of socializing and cultural life. The move helped Garcia Lorca's development as a writer, however, for some of the major trends of modern European culture were just beginning to reach Spain through Madrid's intellectual community. As Western writers began to experiment with language, Madrid became a center of ultraism, which sought to change the nature of poetry by abandoning sentiment and moral rhetoric in favor of "pure poetry"--new and startling images and metaphors. Surrealism, aided by Sigmund Freud's studies of psychology, tried to dispense with social convention and express the hidden desires and fears of the subconscious mind. New ideas surrounded Garcia Lorca even in his dormitory--an idealistic private foundation, the Residencia de Estudiantes, which tried to re-create in Spain the lively intellectual atmosphere found in the residence halls of England's elite universities. At the Residencia Garcia Lorca met such talented students as Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali, who soon became prominent in the surrealist movement. The friendship between Garcia Lorca and Dali became particularly close, and at times painful to both. Dali, somewhat withdrawn in his youth, resisted becoming Garcia Lorca's lover but was clearly drawn to his friend's ebullient personality. Garcia Lorca, who came to view Dali with feelings of unrequited love, was impressed by his friend's audacity as a social critic and as a painter. "You are a Christian tempest," Dali told Garcia Lorca, according to Gibson, "and you need my paganism." Garcia Lorca's early poems, Cobb suggested, show his "search . . . for a permanent manner of expression"; the results are promising but sometimes awkward. Garcia Lorca quickly showed a gift for imagery and dramatic imagination, adeptly describing, for instance, the experience of a bird being shot down by a hunter.

Garcia Lorca had to struggle to shed the vague, overemotional style of romanticism, a difficult task because he often seemed to be making veiled comments about his unhappiness as a homosexual. For example, his poem about the doomed love of a cockroach for a butterfly became an artistic disaster when it was presented in 1920 as the play El maleficio de la mariposa (The Butterfly's Evil Spell). Garcia Lorca's Madrid audience derided the play, and even when he became a successful dramatist he avoided discussing the experience. A more successful poem, which Gibson called "one of Garcia Lorca's most moving," is "Encuentro" ("Meeting"), in which the poet speaks with the loving wife he might have known as a heterosexual. (At his death Garcia Lorca left behind many unpublished works--generally dominated by frustration or sadness--on homosexual themes, apparently presuming that the general public would not accept the subject matter.) Garcia Lorca tried many poetic forms, particularly in Canciones (Songs), which contains poems written between 1921 and 1924. He wrote several extended odes, including the "Ode to Salvador Dali," which was widely praised as a defense of modern art although it can also be read as a love poem.

Discovers the Music of the Gypsies

The form and rhythm of music inspired a group of poems titled Suites, which were not published as a unified collection until 1983. Eventually Garcia Lorca achieved great success as a poet by describing the traditional world of his childhood with a blend of very old and very contemporary writing techniques. The impetus came from his friendship with Manuel de Falla, a renowned composer who moved to Granada to savor the exotic music of Andalusia's gypsies and peasants. The two men rediscovered the gypsies' cante jondo or "deep song," a simple but deeply felt form of folk music that laments the struggles of everyday life. For Garcia Lorca, the ancient cante jondo became a model for innovative poetry: it expressed human feeling in broad terms while avoiding the rhetorical excess of romanticism. While helping Falla to organize a 1922 cante jondo festival that drew folk singers from throughout Spain, Garcia Lorca wrote the poetry collected in Poema del cante jondo (Poem of the Deep Song). In these verses, Gibson observed, he tried to convey the emotional atmosphere of the folk songs while avoiding the awkward pretense that he was an uneducated gypsy. Thereafter Garcia Lorca discovered that he could increase the dramatic impact of his folk-inspired poetry by using the narrative form of old Spanish ballads to tell poetic stories about gypsies and other characters; the poems could attain a twentieth-century outlook by using innovative language and a sophisticated understanding of the human mind. The resulting work, Romancero gitano (Gypsy Ballads), appeared in 1928 and soon made its author famous throughout the Hispanic world.

Gypsy Ballads shows Garcia Lorca at the height of his skill as a poet, in full control of language, imagery, and emotional suggestion. The characters inhabit a world of intense, sometimes mysterious, emotional experience. In the opening ballad a gypsy boy taunts the moon, which appears before him as a sexually attractive woman; suddenly the moon returns to the sky and takes the child with her, while other gypsies wail. Critics have explained the ballad as everything from a comment on Garcia Lorca's sense of being sexually "different" to a metaphor for death. Some of the ballads appear to celebrate sexual vitality. In an unusually delicate poem, Garcia Lorca describes a gypsy nun who is fleetingly aroused by the sound of men on horseback outside her convent; in another a gypsy man describes his nighttime tryst with a woman by a riverbank. Much of the book conveys menace and violence: a girl runs through the night, her fear of being attacked embodied by the wind, which clutches at her dress; a gypsy is murdered by others who envy his good looks; in the final ballad, derived from the Bible, a prince rapes his sister. In his lecture "On the Gypsy Ballads," reprinted in Deep Song, and Other Prose, Garcia Lorca suggests that the ballads are not really about gypsies but about pain--"the struggle of the loving intelligence with the incomprehensible mystery that surrounds it." "Lorca is not deliberately inflicting pain on the reader in order to shock or annoy him," wrote Roy Campbell in Lorca, but the poet "feels so poignantly that he has to share this feeling with others." Observers suggest that the collection describes the force of human life itself--a source of both energy and destructiveness. The intensity of Gypsy Ballads is heightened by its author's mastery of the language of poetry. "Over the years," observed Cobb in his translation of the work, "it has become possible to speak of the `Lorquian' metaphor or image, which [the poet] brought to fruition" in this volume. When Garcia Lorca says a gypsy woman bathes "with water of skylarks," Cobb explained, the poet has created a stunning new image out of two different words that describe something "soothing."

Sometimes Garcia Lorca's metaphors boldly draw upon two different senses: he refers to a "horizon of barking dogs," for instance, when dogs are barking in the distance at night and the horizon is invisible. Such metaphors seem to surpass those of typical avant-garde poets, who often combined words arbitrarily, without concern for actual human experience. Garcia Lorca said his poetic language was inspired by Spanish peasants, for whom a seemingly poetic phrase such as "oxen of the waters" was an ordinary term for the strong, slow current of a river. Campbell stressed that Garcia Lorca was unusually sensitive to "the sound of words," both their musical beauty and their ability to reinforce the meaning of a poem. Such skills, practiced by Spain's folksingers, made Garcia Lorca "musician" among poets, Campbell averred; interestingly, Garcia Lorca greatly enjoyed reading his work aloud before audiences and also presented Spanish folk songs at the piano. Reviewers often lament that Garcia Lorca's ear for language is impossible to reproduce in translation.

Moves to New York

Garcia Lorca's newfound popularity did not prevent him from entering an unusually deep depression by 1929. Its causes, left vague by early biographers, seem to have been the breakup of his intense relationship with a manipulative lover and the end of his friendship with Dali. At Bunuel's urging Dali had moved to Paris, where the two men created a bizarre surrealist film titled Un Chien andalou ("An Andalusian Dog"). Garcia Lorca was convinced that the film, which supposedly had no meaning at all, was actually a sly effort to ridicule him. The poet, who knew no English and had never left Spain, opted for a radical change of scene by enrolling to study English at Columbia University. In New York Garcia Lorca's lively and personable manner charmed the Spanish-speaking intellectual community, but some have surmised that inwardly he was close to suicide. Forsaking his classes Garcia Lorca roamed the city, cut off from its citizens by the language barrier. He found most New Yorkers cold and inhuman, preferring instead the emotional warmth he felt among the city's black minority, whom he saw as fellow outcasts. Meanwhile he struggled to come to terms with his unhappiness and his sexuality.

The first product of Garcia Lorca's turmoil was the poetry collection Poeta en Nueva York (Poet in New York). In this work, Cobb observed, New York's social problems mirror Garcia Lorca's personal despair. Weinstein noted: "Lorca's natural ability to acquaint himself with a place, its underground, its secrets, its genius, its roots, its rot, was phenomenal. And it was this knack for locale that he displayed as no other poet during his stay in New York." The work opens as the poet reaches town, already deeply unhappy; he surveys both New York's troubles and his own; finally, after verging on hopelessness, he regathers his strength and tries to resolve the problems he has described. Poet in New York is far more grim and difficult than Gypsy Ballads, as Garcia Lorca apparently tries to heighten the reader's sense of alienation. The liveliness of the earlier volume gives way to pessimism; the verse is unrhymed; and, instead of using vivid metaphors about the natural world, Garcia Lorca imitates the surrealists by using symbols that are strange and difficult to understand. In poems about U.S. society Garcia Lorca shows a horror of urban crowds, which he compares to animals, but he also shows sympathy for the poor. Unlike many white writers of his time, he is notably eloquent in describing the oppression of black Americans, particularly in his image of an uncrowned "King of Harlem"--a strong-willed black man humiliated by his menial job. Near the end of the collection he predicts a general uprising in favor of economic equality and challenges Christianity to ease the pain of the modern world.

In more personal poems Garcia Lorca contrasts the innocent world of his childhood with his later unhappiness, alludes to his disappointments in love, and rails at the decadence he sees among urban homosexuals. He seems to portray a positive role model in his "Ode to Walt Whitman," dedicated to the nineteenth-century poet--also a homosexual--who attempted to celebrate common people and the realities of everyday life. Garcia Lorca's final poem is a song about his departure from New York for Cuba, which he found much more hospitable than the United States. Commentators disagreed greatly about the merits of Poet in New York, which was not published in its entirety until after Garcia Lorca's death. Many reviewers, disappointed by the book's obscure language and grim tone, have dismissed it as a failed experiment or an aberration. By contrast, Cobb declared that "with the impetus given by modern critical studies and translations, Poet in New York has become the other book which sustains Lorca's reputation as a poet." Before Garcia Lorca returned to Spain in 1930, he had largely completed what many observers would call his first mature play, El publico (The Public). Written in a disconcerting, surrealist style comparable to Poet in New York, the play confronts such controversial themes as the need for truth in the theater and for truth about homosexuality, in addition to showing the destruction of human love by selfishness and death.

Focuses on Writing Plays

After his disastrous experience with "The Butterfly's Evil Spell," Garcia Lorca spent the 1920s gradually mastering the techniques of drama, beginning with the light, formulaic Spanish genres of farce and puppet plays. From puppet theater, observers have suggested, Garcia Lorca learned to draw characters rapidly and decisively; in farces for human actors he developed the skills required to sustain a full-length play. For instance, the farce La zapatera prodigiosa (The Shoemaker's Prodigious Wife), begun in the mid-1920s, shows the writer's growing ease with extended dialogue and complex action. In Amor de Don Perlimplin con Belisa en su jardin (The Love of Don Perlimplin with Belisa, in His Garden), begun shortly thereafter, Garcia Lorca toys with the conventions of farce, as the play's object of ridicule--an old man with a lively young wife--unexpectedly becomes a figure of pity. By 1927 Garcia Lorca gained modest commercial success with his second professional production, Mariana Piñeda. The heroine of this historical melodrama meets death rather than forsaking her lover, a rebel on behalf of democracy. By the time the play was staged, however, Garcia Lorca said he had outgrown its "romantic" style.

Accordingly, in The Public Garcia Lorca proposed a new theater that would confront its audience with uncomfortable truths. As the play opens, a nameless director of popular plays receives three visitors who challenge him to present the "theater beneath the sand"--drama that goes beneath life's pleasing surface. The three men and the director rapidly change costumes, apparently revealing themselves as unhappy homosexuals, locked in relationships of betrayal and mistrust. The director then shows his audience a play about "the truth of the tombs," dramatizing Garcia Lorca's pessimistic belief that the finality of death overwhelms the power of love. Apparently the director reshapes William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, in which young lovers die rather than live apart from each other. In The Public Juliet appears on stage after her love-inspired suicide, realizing that her death is meaningless and that she will now remain alone for eternity. The director's audience riots when faced with such ideas, but some theater students, perhaps representing the future of drama, are intrigued. Back in Spain Garcia Lorca read The Public to friends, who were deeply shocked and advised him that the play was too controversial and surrealistic for an audience to accept. Garcia Lorca apparently agreed: he did not release the work and, according to biographer Reed Anderson, dismissed it in interviews as "a poem to be booed at." Nonetheless, Garcia Lorca observed, it reflected his "true intention."

Garcia Lorca remained determined to write plays rather than poetry, but he reached what some have called an unspoken compromise with his audience, presenting innovative theater that would not provoke general outrage. He became artistic director of the University Theater, a state-supported group of traveling players known by its Spanish nickname, La barraca ("The Hut"). The troupe, which presented plays from the seventeeth-century Golden Age of Spanish drama, was welcomed by small villages throughout Spain that had never seen a stage performance. Garcia Lorca, who gained invaluable experience in theater by directing and producing these programs, decided that an untapped audience for challenging drama existed among Spain's common people. In a manner reminiscent of the Gypsy Ballads, he wrote a series of plays set among the common people of Spain, discussing such serious themes as human passion, unrequited love, social repression, the passing of time, and the power of death.

Rather than shock by discussing homosexuality as in The Public, he focused on the frustrations of Spain's women. As the plays emerged, Garcia Lorca spoke of bringing "poetry" to the theater. But his characters often speak prose, and observers suggest he was speaking somewhat metaphorically. Like other playwrights of his time, Garcia Lorca seems to have felt that the nineteenth-century dramatist's emphasis on realism--accurate settings, everyday events--distracted writers from deeper, emotional truths about human experience. To make theater more imaginative and involving, Garcia Lorca used a variety of effects: vivid language, visually striking stage settings, and heightened emotions ranging from confrontation to tension and repression. By adding such "poetry" to scenes of everyday Spanish life, he could show audiences the underlying sorrows and desires of their own lives.

In accord with such aims, Garcia Lorca's four best-known plays from the 1930s--Doña Rosita la soltera (Doña Rosita the Spinster), Bodas de sangre (Blood Wedding), Yerma, and La casa de Bernarda Alba (The House of Bernarda Alba)--show notable similarities. All are set in Spain during Garcia Lorca's lifetime, and all spotlight ordinary women struggling with the impositions of Spanish society. Doña Rosita is set in the Granada middle class that Garcia Lorca knew as a teenager. In three acts set from 1885 to 1911, Lorca first revels in nostalgia for turn-of-the-twentieth-century Spain, then shows Rosita's growing despair as she waits helplessly for a man to marry her. By the play's end, as Rosita faces old age as an unwanted, unmarried woman, her passivity seems as outdated as the characters' costumes. The three remaining plays, called the "Rural Trilogy," are set in isolated villages of Garcia Lorca's Spain. Yerma's title character is a woman whose name means "barren land." She dutifully allows relatives to arrange her marriage, then gradually realizes, to her dismay, that her husband does not want children. Torn between her desire for a baby and her belief in the sanctity of marriage, Yerma resorts to prayer and sorcery in a futile effort to become a mother. Finally she strangles her husband in a burst of uncontrollable frustration.

In The House of Bernarda Alba, the repressive forces of society are personified by the play's title character, a conservative matriarch who tries to confine her unmarried daughters to the family homestead for eight years of mourning after the death of her husband. The daughters grow increasingly frustrated and hostile until the youngest and most rebellious commits suicide rather than be separated from her illicit lover. Blood Wedding is probably Garcia Lorca's most successful play with both critics and the public. A man and woman who are passionately attracted to each other agree to enter loveless marriages with others out of duty to their relatives, but at the woman's wedding feast the lovers elope. In one of the most evocative and unconventional scenes of all Garcia Lorca's plays, two characters representing the Moon and Death follow the lovers to a dark and menacing forest, declaring that the couple will meet a disastrous fate. The woman's vengeful husband appears and the two men kill each other. The play ends back at the village where the woman, who has lost both her husband and her lover, joins other villagers in grieving but is isolated from them by mutual hatred. In each of the four plays, an individual's desires are overborne by the demands of society, with disastrous results.

Visits South America

After Blood Wedding premiered in 1933, Garcia Lorca's fame as a dramatist quickly matched his fame as a poet, both in his homeland and in the rest of the Hispanic world. A short lecture tour of Argentina and Uruguay stretched into six months, as he was greeted as a celebrity and his plays were performed for enthusiastic crowds. He was warmly received by such major Latin American writers as Chile's Pablo Neruda and Mexico's Alfonso Reyes. Neruda, who later won the Nobel Prize for his poetry, called Garcia Lorca's visit "the greatest triumph ever achieved by a writer of our race." Notably, while Garcia Lorca's most popular plays achieved great commercial success with Spanish-speaking audiences, they have been respected, but not adulated, by the English-speaking public. Some observers have suggested that the strength of the plays is limited to their language, which is lost in translation. But others, including Spaniard Angel del Rio and American Reed Anderson, have surveyed Garcia Lorca's stagecraft with admiration. In the opening scenes of Blood Wedding, for instance, Garcia Lorca skillfully contrasts the festive mood of the villagers with the fierce passions of the unwilling bride; in Yerma he confronts his heroine with a shepherd whose love for children subtly embodies her dreams of an ideal husband. In an article that appeared in Lorca: A Collection of Critical Essays, del Rio wondered if the plays were too steeped in Hispanic culture for other audiences to easily appreciate.

Garcia Lorca's triumphs as a playwright were marred by growing troubles in Spain, which became divided between hostile factions on the political left and right. Though the writer steadily resisted efforts to recruit him for the Communist party, his social conscience led him to strongly criticize Spanish conservatives, some of whom may have yearned for revenge. Meanwhile he seemed plagued by a sense of foreboding and imminent death. He was shocked when an old friend, retired bullfighter Ignacio Sanchez Mejias, was killed by a bull while attempting to revive his career in the ring. Garcia Lorca's elegy--Llanto por Ignacio Sanchez Mejias (Lament for the Death of a Bullfighter)--has often been called his best poem, endowing the matador with heroic stature as he confronts his fate. Later, friends recalled Garcia Lorca's melodramatic remark that the bullfighter's death was a rehearsal for his own. Weinstein contended that Garcia Lorca "was driven by despair to write possibly the greatest elegy of the century. . . . Llanto por Ignacio Sanchez Mejias (Lament for the Death of a Bullfighter, 1935) is a four-part invention about the death of a great bullfighter. (In Spain not even artists root for the bull.) Sanchez was also a great patron of poets. He wrote poetry himself (not great). Most of all he was a great friend. Lorca saw in his death the fall of the courage and sensitivity of Spain. He mourned it in this harmonic masterpiece."

Spain's Civil War Begins

In 1936 civil war broke out in Spain as conservative army officers under General Francisco Franco revolted against the liberal government. Garcia Lorca, who was living in Madrid, made the worst possible decision by electing to wait out the impending conflict at his parents' home in Granada, a city filled with rebel sympathizers. Granada quickly fell to rebel forces, who executed many liberal politicians and intellectuals. One was Garcia Lorca, who was arrested, shot outside town, and buried in an unmarked grave. While Franco's regime, which controlled all of Spain by 1939, never accepted responsibility for Garcia Lorca's death, the poet remained a forbidden subject in Spain for many years. "We knew there had been a great poet called Garcia Lorca," recalled film director Carlos Saura in the New York Times, "but we couldn't read him, we couldn't study him."

By the 1950s Garcia Lorca's work was again available in Spain, but it was still difficult to research either his life or his death. Those who knew him avoided discussing his sexuality or releasing his more controversial work; residents of Granada who knew about his execution were afraid to speak. Gradually there emerged a new willingness to understand Garcia Lorca on his own terms, and after Franco died in 1975, Garcia Lorca could be openly admired in his homeland as one of the century's greatest poets--a status he had never lost elsewhere. His legacy endures as a unique genius whose personal unhappiness enabled him to see deeply into the human heart. "When I met him for the first time, he astonished me," Guillen recalled, according to Anderson. "I've never recovered from that astonishment." Weinstein summed him up this way: "Lorca's work brims with sex, death, nature, unnaturalness, love, mysticism, spells, and cures for which there are no known diseases. He admits being influenced by nursery rhymes, lullabies, folk songs, peasant language, Eliot, Keats, Synge, Whitman, Gongora, Cervantes, and Quevedo. . . . He was a traditional, classical, modern postmodernist. He was radical yet not political. He wrote, `I am an anarchist, communist, monarchist, socialist.' His religion is `Muslim-Jewish-Christian-Atheist.' He seems to have been everything but bigoted. For sheer range of work, he rivals Bernard Shaw and Robert Graves. His appreciation is worldwide."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Surname commonly rendered as Lorca; born June 5, 1898, in Fuentevaqueros, Granada, Spain; executed August 19, 1936, in Viznar, Granada, Spain; son of Federico Garcia Rodriguez (a landowner) and Vicenta Lorca (a teacher). Education: Attended University of Granada, 1914-19; received law degree from University of Madrid, 1923; attended Columbia University, 1929.

CAREER

Writer, director, and artist. Artistic director and producer of plays, for University Theater (state-sponsored traveling theater group, known as La Barraca ["The Hut"]), 1932-35. Director of plays, including Blood Wedding, 1933. Lecturer. Illustrator, with work represented in exhibitions. Musician, serving as arranger and pianist for recordings of Spanish folk songs, 1931. Helped to organize Festival of Cante Jondo (Granada, Spain), 1922.

WORKS

POETRY

• 1921: Libro de poemas (title means "Book of Poems"), Maroto (Madrid, Spain).

• 1927: Canciones (1921-1924), [Malaga, Spain], translated by Phillip Cummings as Songs, Duquesne University Press, 1976.

• 1928: Primer romancero gitano (1924-1927) (contains poem "Romance de la guardia civil espanola"), Revista de Occidente (Madrid, Spain), 2nd edition published as Romancero gitano, 1929, translated by Langston Hughes as Gypsy Ballads, Beloit College, 1951, translated by Rolfe Humphries as The Gypsy Ballads, with Three Historical Ballads, Indiana University Press, 1953, translated by Michael Hartnett as Gipsy Ballads, Goldsmith Press (Dublin, Ireland), 1973, translated by Carl W. Cobb as Lorca's "Romancero gitano": A Ballad Translation and Critical Study, University Press of Mississippi, 1983.

• 1931: Poema del cante jondo, Ulises (Madrid, Spain), translated by Carlos Bauer as Poem of the Deep Song/Poema del cante jondo (bilingual edition), City Lights Books (San Francisco, CA), 1987.

• 1933: Oda a Walt Whitman (title means "Ode to Walt Whitman"), Alcancia, translation by Carlos Bauer published in Ode to Walt Whitman, and Other Poems, City Lights Books (San Francisco, CA), 1988.

• 1935: Llanto por Ignacio Sanchez Mejias (title means "Lament for Ignacio Sanchez Mejias"; commonly known as "Lament for the Death of a Bullfighter"), Arbol.

• 1935: Seis poemas galegos (title means "Six Galician Poems"; written in Galician with assistance from others), Nos (Santiago de Compostela).

• 1936: Primeras canciones (title means "First Songs"), Heroe (Madrid, Spain).

• 1937: Lament for the Death of a Bullfighter, and Other Poems (bilingual edition), translation by A. L. Lloyd, Oxford University Press (New York, NY).

• 1939: Poems, translation by Stephen Spender and J. L. Gili, Oxford University Press (Oxford, England).

• 1940: Poeta en Nueva York, Seneca (Mexico), translated by Ben Belitt as Poet in New York (bilingual edition), Grove Press (New York, NY), 1955, translated by Stephen Fredman, Fog Horn Press, 1975, translated by Greg Simon and Steven F. White, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1988.

• 1940: The Poet in New York, and Other Poems (includes "Gypsy Ballads"), translated by Rolfe Humphries, Norton (New York, NY).

• 1943: Selected Poems of Federico Garcia Lorca, translated by Stephen Spender and J. L. Gili, Hogarth Press (London, England), Transatlantic Arts (New York, NY), 1947.

• 1945: Poemas postumos, Canciones musicales, Divan del Tamarit, Mexicanas (Mexico).

• 1949: Siete poemas y dos dibujos ineditos, edited by Luis Rosales, Cultura Hispanica.

• 1955: The Selected Poems of Federico Garcia Lorca (bilingual edition), edited by Francisco Garcia Lorca and Donald M. Allen, New Directions (New York, NY).

• 1960: Lorca, translation and introduction by J. L. Gili, Penguin (New York, NY), 1960-65.

• 1967: (With Juan Ramon Jimenez) Lorca and Jimenez: Selected Poems, translated by Robert Bly, Sixties Press, reprinted, Beacon Press (Boston, MA), 1997.

• 1974: Divan and Other Writings (includes Divan del Tamarit), translated by Edwin Honig, Bonewhistle Press.

• 1979: Lorca/Blackburn: Poems, translated by Paul Blackburn, Momo's Press.

• 1980: The Cricket Sings: Poems and Songs for Children (bilingual edition), translated by Will Kirkland, New Directions (New York, NY).

• 1983: Suites (reconstruction of a collection planned by Lorca), edited by Andre Belamich, Ariel (Barcelona).

• c. 1984: Ineditos de Federico Garcia Lorca: Sonetos del amor oscuro, 1935-1936 (title means "Unpublished Works of Federico Garcia Lorca: Sonnets of the Dark Love, 1935-1936"), compiled by Marta Teresa Casteros, Instituto de Estudios de Literatura Latinoamericana (Buenos Aires, Argentina).

• 1989: Sonnets of Love Forbidden, translated by David K. Loughran, Windson.

• 1988: The Poetical Works of Federico Garcia Lorca, two volumes, edited by Maurer, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1988-1991.

• 1997: At Five in the Afternoon, translated by Francisco Aragon, Vintage (New York, NY).

• Poems represented in numerous collections and anthologies.

• PLAYS

• 1920: El maleficio de la mariposa (two-act; title means "The Butterfly's Evil Spell"), first produced in Madrid, Spain.

• 1927: Mariana Piñeda: Romance popular en tres estampas (three-act; first produced in Barcelona, Spain; originally published as Romance de la muerte de Torrijos in El dia grafico, June 25, 1927), Rivadeneyra (Madrid, Spain), 1928, translated by James Graham-Lujan as Mariana Piñeda: A Popular Ballad in Three Prints in Tulane Drama Review, winter, 1962, translated by Robert G. Havard as Mariana Piñeda: A Popular Ballad in Three Engravings, Aris & Phillips, 1987.

• 1930: La zapatera prodigiosa: farsa violenta (two-act; title means "The Shoemaker's Prodigious Wife"), first produced in Madrid, Spain.

• 1933: El publico (unfinished; produced in San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1978), excerpts published in Los cuatro vientos, 1933, enlarged version published in El publico: Amor, teatro y caballos en la obra de Federico Garcia Lorca, edited by R. Martinez Nadal, Dolphin (Oxford), 1970, revised edition published as El publico: amor y muerte en la obra de Federico Garcia Lorca, J. Moritz (Mexico), 1974, translated as Lorca's "The Public": A Study of an Unfinished Play and of Love and Death in Lorca's Work, Schocken (New York, NY), 1974, original manuscript published by Dolphin, 1976.

• 1933: Bodas de sangre: tragedia (three-act; first produced in Madrid, Spain; translation by Jose A. Weissberger produced in New York as Bitter Oleander, 1935), Arbol, 1935, translated by Gilbert Neiman as Blood Wedding, New Directions (New York, NY), 1939.

• 1933: Amor de Don Perlimplin con Belisa en su jardin (title means "The Love of Don Perlimplin with Belisa, in His Garden"), first produced in Madrid, Spain.

• 1934: Yerma: poema tragico (three-act; first produced in Madrid, Spain), Anaconda (Buenos Aires), 1937, translated by Ian Macpherson and Jaqueline Minett as Yerma: A Tragic Poem (bilingual edition), Aris & Phillips, 1987.

• 1934: Retablillo de Don Cristobal (puppet play; title means "Don Cristobal's Puppet Show;" first produced in Buenos Aires, Argentina; revised version produced in Madrid, Spain, 1935), Subcomisariado de Propaganda del Comisariado General de Guerra (Valencia, Spain), 1938.

• 1935: Doña Rosita la soltera; o, El lenguaje de las flores: Poema granadino del novecientos, (three-act; title means "Dona Rosita the Spinster; or, The Language of Flowers: Poem of Granada in the Nineteenth Century"), first produced in Barcelona, Spain.

• 1937: Los titeres de Cachiporra: tragecomedia de Don Cristobal y la sena Rosita: Farsa (puppet play; title means "The Billy-Club Puppets: Tragicomedy of Don Cristobal and Mam'selle Rosita"; first produced in Madrid, Spain), Losange, 1953.

• 1941: From Lorca's Theater: Five Plays (contains The Shoemaker's Prodigious Wife, The Love of Don Perlimplin with Belisa, in His Garden, Doña Rosita the Spinster, Yerma, and When Five Years Pass [produced as Asi que pasen cinco años in Madrid, 1978]), translated by Richard L. O'Connell and James Graham-Lujan, Scribner (New York, NY), 1941.

• 1944: La casa de Bernarda Alba: drama de mujeres en los pueblos de Espana(three-act; title means "The House of Bernarda Alba: Drama of Women in the Villages of Spain"; first produced in Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1945), Losada.

• 1947: Three Tragedies (contains Blood Wedding, Yerma, and The House of Bernarda Alba), translated by Richard L. O'Connell and James Graham-Lujan, introduction by Francisco Garcia Lorca, New Directions (New York, NY), reprinted, Greenwood Press, 1977, translated by Sue Bradbury, Folio Society (London, England), 1977.

• 1953: Cinco forsas breves; seguidas de "Asi que pasen cinco años, Losange.

• 1954: Comedies (contains The Butterfly's Evil Spell, The Shoemaker's Prodigious Wife, The Love of Don Perlimplin with Belisa, in His Garden, and Dona Rosita the Spinster), translated by Richard L. O'Connell and James Graham-Lujan, introduction by Francisco Garcia Lorca, New Directions (New York, NY), enlarged edition published as Five Plays: Comedies and Tragicomedies (includes The Billy-Club Puppets), 1963, reprinted, Penguin (New York, NY), 1987.

• 1978: El publico [and] Comedia sin titulo: Dos obras postumas, edited by R. Martinez Nadal and M. Laffranque, Seix Barral (Madrid, Spain), translated by Carlos Bauer as The Public [and] Play without a Title: Two Posthumous Plays, New Directions (New York, NY), 1983.

• 1986: Teatro inconcluso, edited by M. Laffranque, Universidad de Granada (Granada, Spain).

• 1987: The Rural Trilogy: Blood Wedding [and] Yerma [and] The House of Bernarda Alba, translated by Michael Dewell and Carmen Zapata, Bantam (New York, NY).

• 1987: Three Plays (contains Blood Wedding, Doña Rosita the Spinster, and Yerma), translated by Gwynne Edwards and Peter Luke, Methuen (London, England).

• 1989: Once Five Years Pass, and Other Dramatic Works, translated by William B. Logan and Angel G. Orrios, Station Hill Press.

• 1989: Two Plays of Misalliance: The Love of Don Perlimplin [and] The Prodigious Cobbler's Wife, Aris & Phillips.

• 1989: Comedia sin titulo (one act of an incomplete play; title means "Play without a Title"; also known as "El sueño de la vida" [title means "The Dream of Life"]), first produced in Madrid, Spain.

• 1991: Barbarous Nights: Legends and Plays from the Little Theater, translated by Christopher Sawyer-Laucanno, City Lights Books (San Francisco, CA).

• 1994: Blood Wedding; and Yerma, introduction by W. S. Merwin, Theatre Communications Group.

• 1997: Four Major Plays (includes Blood Wedding, Yerma, The House of Bernarda Alba, and Doña Rosita the Spinster), translated by John Edmunds, Oxford University Press (New York, NY).

• Also author of short dramatic sketches, including "La donacella, el marinero y el estudiante" (title means "The Maiden, the Sailor, and the Student") and "El paseo de Buster Keaton" (title means "Buster Keaton's Stroll"), both 1928, and "Quimera" (title means "Chimera"). Adapter of numerous plays, including La dama boba and Fuente Ovejuna, both by Lope de Vega. Plays represented in collections and anthologies.

OMNIBUS VOLUMES

• 1938: Obras completas (complete works), edited by Guillermo de Torre, Losada (Buenos Aires, Argentina), 1938-1946.

• 1954: Obras completas, edited with commentary by Arturo de Hoyo, introductions by Jorge Guillen and Vicente Aleixandre, Aguilar.

• 1981: Obras (title means "Works"), edited with commentary by Mario Hernandez, multiple volumes, Alianza, 1981--, 2nd edition, revised, 1983--.

• 1997: Epistolario completo, Catedra (Madrid, Spain).

• OTHER

• 1918: Impresiones y paisajes (travelogue), P. V. Traveset (Granada, Spain), translated by Lawrence H. Klibbe as Impressions and Landscapes, University Press of America, 1987.

• 1950: Federico Garcia Lorca: Cartas a sus amigos (letters), edited by Sebastian Gasch, Cobalto (Barcelona, Spain).

• 1961: Conferencias y charlas, Consejo Nacional de Cultura.

• 1963: Viaje a la luna (filmscript), translation by Richard Diers published as Trip to the Moon, in Windmill, spring, edited by M. Laffranque, Braad, 1980.

• 1968: Garcia Lorca: Cartas, postales, poemas y dibujos (includes letters and poems), edited by Antonio Gallego Morell, Monedo y Credito (Madrid, Spain).

• 1969: Casidas, Arte y Bibliofilia.

• 1969: Prosa, Alianza.

• 1971: Granada, paraiso cerrado y otras paginas granadinas, Sanchez.

• 1975: Autografos, edited by Rafael Martinez Nadal, Dolphin, Volume 1, 1975, Volume 2, 1976, Volume 3, 1979.

• 1980: Deep Song, and Other Prose, translated by Christopher Maurer, New Directions (New York, NY).

• 1981: From the Havana Lectures, 1928: "Theory and Play of the Duende" and "Imagination, Inspiration, Evasion" (lectures; bilingual edition), translated by Stella Rodriguez, preface by Randolph Severson, introduction by Rafael Lopez Pedraza, Kanathos (Dallas, TX).

• 1981: Lola, la comedianta, edited by Piero Menarini, Alianza.

• 1983: Epistolario, two volumes, edited by Christopher Maurer, Alianza, portions translated by David Gershator as Selected Letters, New Directions (New York, NY), 1983.

• 1984: Conferencias, two volumes, edited by Christopher Maurer, Alianza.

• 1984: How a City Sings from November to November (lecture; bilingual edition), translated by Christopher Maurer, Cadmus Editions.

• 1985: Alocuciones argentinas, edited by Mario Hernandez, Fundacion Federico Garcia Lorca/Crotalon.

• 1985: Tres dialogos, Universidad de Granada/Junta de Andalucia.

• 1986: Alocucion al pueblo de Fuentevaqueros, Comision del Cincuecentenario.

• 1986: Dibujos, Ministerio de Cultura (Granada), translated by Christopher Maurer as Line of Light and Shadow: The Drawings of Federico Garcia Lorca, edited by Mario Hernandez, Duke University Press/Duke University Museum of Art, 1991.

• 1989: Treinta entrevistas a Federico Garcia Lorca, edited by Andres Soria Olmedo, Aguilar.

• 1995: Selected Verse, introductions by Christopher Maurer and Francisco Aragon, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY).

• 1998: A Season in Granada: Uncollected Poems and Prose (contains Granada, paraiso cerrado y otras paginas granadinas), edited by Christopher Maurer, Anvil Press Poetry.

• Illustrator of books, including El fin del viaje by Pablo Neruda; drawings published in collections. Co-editor of Gallo (literary magazine; title means "rooster"), 1928.

• Garcia Lorca's manuscripts are housed at Fundacion Garcia Lorca, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, Madrid.