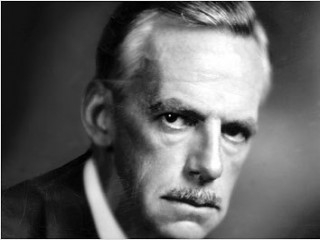

Eugene O'Neill biography

Date of birth : 1888-10-16

Date of death : 1953-11-27

Birthplace : New York City, New York, US

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-04-14

Credited as : Drama writer, and playwright, Nobel Laureat in Literature

Eugene O'Neill was among the foremost dramatists of the America theater. His main concern was with the anguish and turmoil that wrack the spirits of sensitive people.

Eugene O'Neill set out to create meaningful drama in America at a time when the barriers against it were significant. Although outstanding dramatists were getting productions throughout Europe, American dramatists were locked into standard commercial practices by the monopolistic forces controlling the theater. As a result, by the time of O'Neill's first production (1916), the American theater was a quarter century behind European theater. Twenty years later, when O'Neill received the Nobel Prize for literature, America had assumed a leadership position in world drama; O'Neill was preeminent in this rise.

Eugene O'Neill was born on Oct. 16, 1888, in New York City at a hotel on Broadway. His father was James O'Neill, an outstanding romantic actor. Eugene's mother was Ella Quinlan. Eugene had two brothers, James, Jr. (born 1878), and Edmund (born 1883). Edmund's death 2 years later brought deep feelings of guilt into the family.

Eugene spent his first 7 years on tour with his parents. A succession of dreary hotel rooms and a mother addicted to drugs left their impact upon him. He also received a total exposure to theater.

From the age of 7 to 12, Eugene was taught by nuns. His next 2 years were spent under the Christian Brothers. When he rebelled against any further Catholic education, his parents sent him to Betts Academy in Connecticut for high school. He was also learning about life at this time under the guidance of his brother, Jamie, who "made sin easy for him." Eugene's formal education ended with an unfinished year at Princeton University in 1907. By this time his three main interests were evident: books, alcohol, and prostitutes.

O'Neill worked halfheartedly for a mail-order firm until the fall of 1908. In 1909 he secretly married Kathleen Jenkins before leaving on a mining expedition to Honduras, where he contracted malaria. Returning in April 1910, he revealed his marriage because of Kathleen's pregnancy. Eugene O'Neill, Jr., was born the next month.

O'Neill shipped out as a seaman in 1910 and did odd jobs in Buenos Aires, spending almost 6 months as a pan-handler on the waterfront before going to sea again. Back in New York in 1911, he spent several weeks drinking in Jimmy the Priest's saloon before shipping out to England. He returned in August to his old hangout. Almost half his published plays show his interest in the sea.

In 1912 O'Neill hit bottom. His marriage was dissolved, his attempt at suicide failed, and he contracted tuberculosis. But he also decided to become a dramatist. He was released from the sanitarium in June 1913.

Tall and thin, dark-eyed and handsome, with a brooding sensitivity, O'Neill was a man of many paradoxical qualities. Though he was ready to work, he was by no means ready to change his way of living completely. During the next year he wrote prolifically. Except for Bound East for Cardiff, these early plays are finger exercises. With his father's aid, five of these one-act plays were published in 1914. On the basis of this work and with the assistance of the critic Clayton Hamilton, O'Neill joined George Pierce Baker's playwriting class at Harvard in September 1914.

O'Neill planned to return to Harvard in the fall of 1915 but ended up instead at the "Hell Hole," a combination hotel and saloon in New York City, where he drank heavily and produced nothing. He next joined the Provincetown Players on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. The Players' production of Bound East for Cardiffin 1916 signaled a new era in American drama. By the end of 1918, the Players had produced 10 of O'Neill's plays. Such excellent exposure, combined with the support of the critic George Jean Nathan, rocketed O'Neill into prominence. His plays of the sea were most successful, particularly Bound East for Cardiff (1916), In the Zone (1917), The Long Voyage Home (1917), and The Moon of the Caribbees (1918), which are sometimes produced together under the title of S.S. Glencairn.

In his early writing O'Neill concentrated heavily on the one-act form. His apprenticeship in this form culminated in great success with the production of his full-length Beyond the Horizon (1920), for which he won his first Pulitzer Prize. The play is definitely indebted to the one-act form in its structure. Although the drama is essentially naturalistic, O'Neill elevated both characterization and dialogue, and for the first time, by adding a poetic and articulate character, he gave himself the opportunity to reach high dramatic moments.

In 1918 O'Neill married Agnes Boulton. They had a son, Shane, and a daughter, Oona. Meanwhile, O'Neill met his son Eugene, Jr., for the first time in 1922, when the boy was 12 years old. O'Neill's family died in close succession: his father (1920), mother (1922), and brother (1923). Following this tumult, his marriage was troubled; O'Neill had fallen in love with Carlotta Monterey. In 1928 he left Agnes Boulton, divorced in 1929, and soon married Carlotta.

In spite of pressures in his personal life, O'Neill was incredibly productive. In the 15 years following the appearance of Beyond the Horizon, 21 plays were produced. Always daring in his conceptions, always willing to experiment, he brought forth both brilliant successes and atrocious failures.

O'Neill's successful plays reveal interesting experimentation—apart from Anna Christie (1921), a rather standardly organized and realistic play with some romantic overtones which was awarded a Pulitzer Prize, and Ah, Wilderness! (1933), a surprisingly nostalgic comedy unique in the O'Neill canon (both were later adapted to the musical stage). The Emperor Jones (1920) is a superb theatrical piece in which Brutus Jones moves from reality, to conscious memories of his past, to subconscious roots of his ancient heritage, as he flees for his life. The play ends in the reality of his death. Another expressionistic piece, The Hairy Ape (1922), traces the path of a burly stoker shocked into self-awareness by a decadent society woman, as he tries to find out where he belongs in the world.

Two plays deal with the human propensity to hide behind masks. In The Great God Brown (1926), masks are actually used. On his death, Dion Anthony wills his mask to William Brown, who then lives under the impact of dual masks. In Strange Interlude (1928), a massive treatment of the many roles of women as seen in the life of Nina Leeds, O'Neill used spoken "asides" (interior monologues) to disclose his characters' hidden and normally unspoken thoughts. For this play he received his third Pulitzer Prize.

The final successes stem from O'Neill's desire to reach the essence of tragedy. In Desire under the Elms (1924), he probed the tumult of passions burning deep on a New England farm. The peace which Eben and Abby find in their love is decidedly convincing. Ephraim's obdurate persistence also carries the ring of universal truth. Mourning Becomes Electra (1931), also set in New England, is O'Neill's version of Aeschylus's Oresteia. The ancient guilt of the house of Atreus is converted into Freudian terms in the depiction of the Mannon family. O'Neill's "Electra," Lavinia, is powerfully characterized, and her final expiation is a moving end to a most worthy play.

A grim and repulsive drama, Diff'rent (1920), a rather psychopathic portrait of a sexually obsessed woman, garnered mixed reviews. The Straw (1921), a story of love and selfishness dating back to O'Neill's experiences in the sanitarium, was generally accepted. Though All God's Chillun Got Wings (1924) received tremendous publicity before its opening, O'Neill failed to deeply penetrate the realms of myth and bigotry. However, he did achieve a Job-like quality for the black husband. Babbitt and Marco Polo were aligned in a satiric and poetic expression in Marco Millions (1928). The play's best aspect is its pageantry; the poetry is somewhat disappointing.

Lazarus Laughed (1928) was not produced commercially in New York. Essentially a religious-philosophical epic, the play has some interesting scenes but a ponderous, turgid style.

Eight plays were disasters: Chris Christopherson (1920), Gold, (1921), The First Man (1922), Welded (1924), The Ancient Mariner (1924), a dramatization of Coleridge's poem, The Fountain (1925), Dynamo (1929), and Days without End (1934).

Carlotta Monterey brought a sense of order to O'Neill's life. His health deteriorated rapidly from 1937 on, but her care helped him remain productive, though their marriage was not without furor.

In addition to the physical and psychological burdens of his poor health, O'Neill was also disturbed by his continued inability to establish relationships with his children. Eugene, Jr., died by suicide in 1950. Shane became addicted to drugs. Oona was ignored by her father after her marriage to actor Charlie Chaplin. The tragic lack of communication for which O'Neill had accused his father was a major flaw in his own relationships with his children. Indeed, he even excluded Shane and Oona from his will. When O'Neill knew that death was near, one of his final actions was to tear up six of his unfinished cycle plays rather than have them rewritten by someone else. These plays, tentatively entitled "A Tale of Possessors Self-dispossessed," were part of a great cycle of 9 to 11 plays which would follow the lives of one family in America. O'Neill's health prevented him from completing them. He died on Nov. 27, 1953.

With the exception of The Iceman Cometh (1946), all of O'Neill's late works received their New York production after his death. The Iceman Cometh, with its exhibition of pipe dreams in Harry Hope's saloon, fascinated audiences and overcame almost universal complaints about its length. Long Day's Journey into Night (1956), autobiographical in its totality, devoid of theatrical effects, utterly scathing in its insistence on truth, showed O'Neill at the height of his dramatic power. It received the Pulitzer Prize.

A Moon for the Misbegotten (1957) and A Touch of the Poet (1958), inevitably measured against the brilliance of Long Day's Journey into Night, were found to be of a lesser magnitude. In A Moon for the Misbegotten, O'Neill focuses on his brother Jamie. Among all his late plays with their searching realism, A Touch of the Poet has the strongest elements of romantic warmth. Hughie (1964) offers nothing new in its treatment of illusion. More Stately Mansions (1967), a sequel to A Touch of the Poet, is not outstanding.