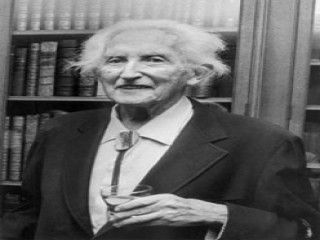

Erik Erikson biography

Date of birth : 1902-06-15

Date of death : 1994-05-12

Birthplace : Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Nationality : German

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2011-04-10

Credited as : psychoanalyst and educator , Martin Luther, Young Man Luther , Identity and the Life Cycle

Erik Homburger Erikson was a German-born American psychoanalyst and educator whose studies have perhaps contributed most to the understanding of the young.

On June 15, 1902, Erik Erikson was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, of Danish parents. His widowed mother subsequently married the pediatrician Theodore Homburger. Erikson first studied painting in Germany and Italy. Later, he joined Peter Blos and Dorothy Burlingham, Anna Freud's colleague, in the development of a small children's school in Vienna. This led to his training analysis by Anna Freud and immersion in theoretical seminars and in clinical work. Having also acquired a Montessori diploma, he graduated from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute in 1933.

In 1930, he had married Canadian-born Joan Mowat Serson, who was vitally interested in education, as well as the arts and crafts, and deeply shared his interest in writing. The development of their three children, Kai, Jon, and Sue, as well as Erikson's work in Anna Freud's school, may have contributed much to his eventual thinking about the "epigenetic schema" of development and the vocabulary of health, in which he described the contributions of successive psychosexual stages to ego strengths, such as trust and autonomy, initiative and industry, and identity and intimacy.

Following Hitler's accession to power, the Eriksons went to the United States, where he began private practice and a sequence of research appointments at Harvard Medical School (1934-1935), Yale School of Medicine (1936-1939), University of California at Berkeley (1939-1951), and Austen Riggs Center, Stockbridge, Mass. (1951-1960); he was visiting professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (1951-1960). One of his later appointments was as professor of human development and lecturer in psychiatry at Harvard University. At intervals he took time off for work abroad, such as travel to India in connection with his intensive study of Gandhi.

Always free from the provincialism typical of thinkers with a more static and limited background, Erikson's thinking pushed toward an understanding of the ways in which the drives dominant in successive psychoanalytically defined life stages are shaped by interaction with the persistent needs and solutions typical of a given culture. These formulations were supported by field observations made with the collaboration of anthropologists, and also by observations of children's play.

Erikson's extension of the classical Freudian psychoanalytic concept of development was published in Childhood and Society (1950). The book startled some orthodox Freudians, who viewed development as dominated solely by the sequential emergence of successively potent drives modified or exaggerated primarily by their intimate—depriving, indulging, or punishing—interactions with the parents. Erikson's broader concept of dynamics of inner-outer interactions provided inspiration, challenge, and insight to the spectrum of American social sciences concerned with child development.

Erikson's concern at Austen Riggs Center was focused on the troubled years of late adolescence and early adulthood. He emphasized the universal process of resolution of identity conflicts during this developmental phase in a profound study of the youthful Martin Luther, Young Man Luther (1958); in a monograph, Identity and the Life Cycle (1959); and in a volume which he edited, Youth: Change and Challenge (1963). His Harvard teaching and response to students' concerns with values led to two collections of essays: Insight and Responsibility (1964) and Identity, Youth and Crisis (1967). The latter is a prophetic reformulation of the relation of the concepts of ego and self, and recognition of issues of nobility and cowardice, love and hate, and greatness and pettiness, which he sees as transcending the traditional normative issues of "adjustment to society." His contribution to understanding of the problem of identity in youth at times when personal change intersects with historical change has led scores of scholars to research exploring this area. In 1969 Erikson published Gandhi's Truth. This book focuses on the evolution of a passionate commitment in maturity to a humane goal and on the inner dynamic precursors of Gandhi's nonviolent strategy to reach this goal.

The sources of Erikson's fresh, subtle, and multimodal awareness are many: His artist's temperament and perceptiveness contribute both to sensory richness and to sensitivity to nuances of personality and behavior. His deeply satisfying family life and wide-ranging friendships, with people such as Lawrence K. Frank, Margaret Mead, A. L. Kroeber, and Gardner Murphy, support a sense of health as a potential for the development of human beings struggling with conflicts exacerbated by the pressures of a given life stage. His freedom from premature commitment to an academic discipline with rigid canons of concept formation released him for original formulations as well as new adaptations and implications of classical psychoanalysis. Erikson's shrewd "the Emperor has no clothes" type of realism and uninhibited daring in probing new areas of experience seem to draw on a never-suppressed child's penetrating curiosity.

His love of life in nature and in people of all ages and many different cultures underlies the predominantly warm and vital quality of his thinking and writing. This has evoked the resonance of students of many disciplines whom he has influenced more than any analyst since Freud.

Freud lived and worked at a time when the mentally ill were beginning to be understood and universal inner conflict needed to be understood more deeply. Erikson was maturing in a period when the fate of the Western world was threatened by violence and denigration of values—a time when health, "virtue," and strength and their origins needed to be asserted and understood. His later books anticipated the demands of youthful protesters who repudiated the falseness of politics and the materialism of the economic world and who called for sincerity, peace, love, and humane values.

Erikson died in 1994; however, his words live on— even those not familiar with his work may share his passion in language. Along with his numerous theories and plethora of information, Erikson also left educators the sound advice, "Do not mistake a child for his symptom."