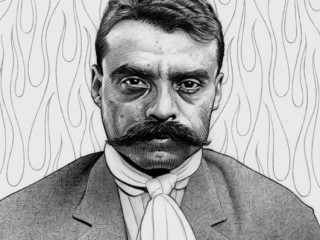

Emiliano Zapata biography

Date of birth : 1879-08-08

Date of death : 1919-04-10

Birthplace : Anenecuilco, Morelos, Mexico

Nationality : Mexican

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2011-04-02

Credited as : Agrarian leader, guerrilla fighter, leading figure in the Mexican Revolution

Emiliano Zapata, Mexican agrarian leader and guerrilla fighter, was the symbol of the agrarian revolution.

Emiliano Zapata was born in Anenecuilco, Morelos, to a landless, but not poor, family which dealt in livestock. Orphaned at 16, he sharecropped and traded horses in his birth-place. During the closing years of the Porfirio Diaz dictatorship Zapata took part in local opposition politics, with a 6-month interruption while he served as a soldier.

In September 1909 Zapata was elected president of the group in Anenecuilco designated to reclaim the community's ejidal lands. He backed the unsuccessful opposition gubernatorial candidacy of Patricio Leyva. In March 1911, after several months of contact with the maderistas, Zapata joined the rebellion against Diaz. The major effort of the zapatistas was an attack on Cuautla.

With the fall of the Diaz regime Zapata initiated his recurring demands—land for the peasants, removal of federal troops from Morelos, and designation of an acceptable commander of state forces. The efforts of the interim De la Barra regime, endorsed by Francisco Madero, to discharge the revolutionary forces irritated Zapata, who became incensed when during the Madero's pacification efforts Francisco de la Barra ordered Victoriano Huerta to march into Morelos in August 1911.

Zapata's view of revolutionary goals was quite parochial, and he was unwilling to await patiently the results of Madero's dreamed-of democratic processes to effect land reform. Nineteen days after Madero assumed the presidency, Zapata revolted under the Plan of Ayala. Waging guerrilla warfare, as he had before and would again, Zapata began distribution of ejidal lands in Puebla in April 1912 and followed with other distributions in Morelos and Tlaxcala. Agricultural students were employed in the formation of agrarian commissions. Program and strategy for the moustached and almost illiterate Zapata were formulated by a group of intellectuals, including Antonio Diaz Soto y Gama and schoolteacher Otilio Montano.

After Madero's death, Zapata joined with Pancho Villa and Venustiano Carranza in an uneasy alliance to defeat Huerta. However, it was the carrancistas who occupied Mexico City, and the First Chief (Carranza) sought to control the situation through the Convention of Generals. Villista and zapatista opposition forced removal of the gathering to Aguascalientes, where the representatives of Zapata had the first public and national hearing of their cause.

The Plan of Ayala was accepted in principle, and the convention government was established, resting on the armed support of Villa and Zapata. Their joint armies occupied the Mexican capital in December 1914. However, cooperation in subsequent military operations was another matter. As Ãlvaro Obregon led his Constitutionalist army back toward Mexico City, Villa withdrew to the north and Zapata turned back southward into Morelos.

From 1915 on Zapata waged defensive guerrilla warfare against the Constitutionalist. Forces under Gen. Pablo Gonzalez sought, as others before, to wipe out the zapatistas without success. Finally, Gonzalez sent Col. Jesus Guajardo to trick Zapata into receiving him as an ally. Zapata was ambushed and killed at Chinameca on April 10, 1919. However, there were those who insisted that he was not dead, that he had been seen riding his horse in the sierra watching out for his peasants. A little more than a year later the demands of the zapatistas were being met by the Obregon government.

The excellent, scholarly work by John Womack, Zapata and the Mexican Revolution (1969), catches the essence of Zapata and the spirit of zapatismo. Edgecumb Pinchon, Zapata: The Unconquerable (1941), is a romanticized study, and H. H. Dunn, The Crimson Jester: Zapata of Mexico (1933), is a more sketchy and less sympathetic account. Ronald Atkin's competent review of the factors that contributed to the uprising, Revolution: Mexico, 1910-20 (1970), contains a good portrait of Zapata and of other major figures of the time. Robert P. Millon, Zapata: The Ideology of a Peasant Revolutionary (1969), is a Marxist interpretation. Also useful are Frank Tannenbaum, The Mexican Agrarian Revolution (1929), and Eyler N. Simpson, The Ejido (1937).