El Greco biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Candia, Crete

Nationality : Greek

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2011-03-23

Credited as : Artist painter, Palazzo Farnese, chapel S. Jose Toledo

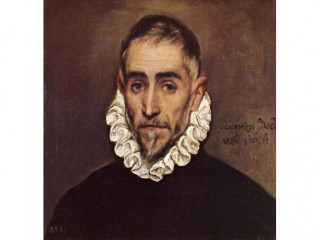

El Greco (1541-1614), a Greek painter who settled in Spain, evolved a highly personal style with mannerist traits. He was a great religious painter of a visionary nature and a master portraitist.

El Greco is regarded as one of the greatest painters of all time. He was rescued from critical and popular neglect by the French impressionists in the late 19th century, but his rise to fame came with the reevaluations of the first decade of the 20th century. El Greco's mature art, which is notable for its emotional expressionism rather than realism or idealism in the neoclassic sense, fulfilled the concepts of the new cult of expressionism at the beginning of the 20th century.

El Greco, whose real name was Domenikos Theotokopoulos, was born in Candia, Crete, in 1541, according to his own statement. The artist must have had some preparation as a painter before he went to the great artistic center of Venice. Since Crete was a Venetian possession during that period, he logically chose to go to Venice rather than to Florence or Rome. The precise date of his arrival in Italy is unknown; it may have been as early as 1560. The fact that he witnessed a document in Candia in 1566 has caused some writers to insist that his first voyage to Venice came later, yet he may have returned to Crete for a visit the year of his father's death (1566). During his stay in Italy he became known as II Greco ("the Greek") because his name was too difficult to pronounce. Later, in Spain, he was called El Greco.

El Greco was said to be a pupil of Titian in a letter the miniaturist Giulio Clovio wrote to Cardinal Alessandro Farnese on Nov. 16, 1570, asking that the young man be given lodging in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. El Greco's trip to Rome in 1570 is thus proved, and he was still there on Oct. 18, 1572, when he paid his dues to the painters' guild of St. Luke. It is speculated that he subsequently returned from Rome to Venice and that he departed for Spain in 1576, possibly because of a plague in Venice.

The story has often been repeated that Giulio Clovio visited the young painter in Rome and found that he had closed his blinds on a sunny day because the light of day would destroy his inner light. That tale was invented by a Yugoslavian student studying in Munich in 1922-1923. A much earlier fabrication given circulation by Giulio Mancini (ca. 1614-1621) holds that El Greco had to flee from Rome to Spain because he had criticized Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel and said that he could do better.

Various reasons for El Greco's migration to Spain have been advanced, among them that he hoped for commissions to work at the great monastery of the Escorial, which King Philip II had begun in 1536. El Greco knew that Philip had been a great patron of Titian, who provided several religious compositions for the Escorial as well as mythological pictures and portraits for Philip's art collection. Another probable enticement was the advance promise of a commission for the altars for the church of S. Domingo el Antiguo in Toledo.

In 1577 El Greco arrived in Madrid and soon visited Toledo. There he executed his first great commission, the high altar and the two lateral altars of S. Domingo el Antiguo, and the Espolio, or Disrobing of Christ, in the Cathedral (both 1577-1579). A controversy over payment for the latter work led to a litigation, the preserved document for which provides valuable information about El Greco at the beginning of his Spanish years, when he still understood little Castilian.

At this time El Greco formed a liaison with a young woman, Dona Jeronima de las Cuevas, by whom he had a son, Jorge Manuel Theotocopuli (1578-1631). El Greco's failure to marry her despite the respectful reference to her in his last testament has given rise to considerable speculation. The possibility that he left an estranged wife in Italy is by no means unreasonable.

El Greco's only connection with Philip II and the Spanish court occurred in the early Spanish years, when he painted the Allegory of the Holy League (1578-1579) and the Martyrdom of St. Maurice (1580-1582; both Escorial). That Philip did not like the latter picture is reported by the contemporary historian of the Escorial, Padre Sigüenza.

El Greco settled in Toledo between 1577 and 1579, and there he remained until his death on April 6 or 7, 1614. His fame spread to other parts of Spain, but most of his commissions were in Toledo and the vicinity.

El Greco was a Renaissance man of great culture, familiar with Greek and Latin literature as well as Italian and Spanish. His remarkable library, the inventory of which is known, demonstrates his broad humanistic interests. He owned copies of the architectural treatises of Leon Battista Alberti, Giacomo da Vignola, Andrea Palladio, and Sebastiano Serlio. El Greco prepared an edition of the Roman architectural treatise of Vitruvius, which has been lost.

El Greco numbered among his intimate friends the leading humanists and intellectuals of Toledo, men such as the scholar Antonio de Covarrubias, Pedro Salazar de Mendoza, Fray Hortensio Paravicino, and the poet Luis de Góngora y Argote. The last two men wrote poems about El Greco's works.

Two works signed by Master Domenikos, an icon (Athens) and a small portable triptych (Modena), have frequently been attributed to El Greco, but, as the patronym is lacking, his authorship cannot be established with certainty. After World War II a vast number of mediocre panels by so-called Madonna painters (Madonneri) were attributed to the youthful El Greco, but they have now been discredited.

Signed works of this period by El Greco include the Purification of the Temple (Washington and Minneapolis), Christ Healing the Blind (Parma), St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata (Geneva and Naples), Pietà (Philadelphia), Boy Lighting a Candle (Manhasset), and the portraits Giulio Clovio (Naples) and Vincenzo Anastagi (New York). At this time he signed his paintings in Greek capital letters. His style is notably Venetian in richness of color and illusionistic application of the paint. His interest in the composition of deep space reveals his knowledge of Raphael's murals in the Vatican, Serlio's books on architecture, and contemporary developments in Venice.

El Greco's first masterpiece of this period is the Assumption of the Virgin (signed and dated 1577; Chicago) from the high altar of S. Domingo el Antiguo, Toledo. Based on Titian's Assumption in the church of S. Maria dei Frari in Venice, it nevertheless shows independence in spatial organization and technical brilliance in the colors. The powerful physical types and certain poses in the Trinity (Madrid) from the same altar reveal El Greco's admiration of the heroic concepts of Michelangelo, whose art he had obviously studied in Rome. At the same time El Greco's color and technical procedures remain Venetian. The Espolio (1577-1579; sacristy of Toledo Cathedral) shows even greater originality in the composition: the figures are brought into the foreground, largely excluding depth, in a way that constitutes El Greco's interpretation of mannerism. But the medieval Byzantine tradition is reflected in the way the heads of the tormentors are placed in superimposed rows.

Masterpieces followed with such rapidity and in such great quantity that only a few can be mentioned. The Martyrdom of St. Maurice (1580-1582; Escorial) is astonishing in the brilliance of color, with the yellow against the blue producing a dazzling effect. The pale tonalities have antecedents in late Roman mannerism, but El Greco achieved expressionistic results using them. Other important paintings are the Crucifixion with Two Donors (Paris) and the Holy Family (New York).

This period culminated in the large canvas Burial of the Conde de Orgaz (1586-1588; church of S. Tome, Toledo), a work that, combining all aspects of the artist's genius, is generally regarded as his greatest masterpiece and one of the outstanding paintings of all time. The figures are brought into a wall-like composition in the foreground, eliminating space in depth, a method that characterizes mannerism as distinguished from the deep space of High Renaissance composition. Some portraits of El Greco's Toledan contemporaries in the burial scene are identifiable. They are presented in normal human proportions, but the extreme elongation and distortion of the figures in heaven combined with the glacial clouds create a vision of a supernatural world.

El Greco maintained a sense of idealism in his late pictures when the subject demanded it, as in his lovely conception of the Madonna in the Holy Family with St. Anne (Hospital of St. John Extra Muros, Toledo) and the Holy Family with the Magdalen (Cleveland; both ca. 1590-1595). In these compositions the figures are brought into the foreground with only the sky as background, a method of organization that is distinctly mannerist.

El Greco received a number of important commissions at this time. The high altar (1597-1599) of the chapel of S. Jose, Toledo, is dedicated to St. Joseph with the Christ Child, tenderly interpreted with the tall otherworldly Joseph crowned from above by the wildly distorted and foreshortened angels; the city of Toledo is seen in the background. St. Martin Dividing His Cloak with the Beggar and the Madonna with Saints Agnes and Martina (both Washington) originally occupied the lateral altars of the same chapel. St. Martin impresses the spectator because of the extreme elongation of the partly nude body of the pathetic young beggar. Here El Greco's personal interpretation is fully in evidence in his use of mannerist elongation, a trait widely characteristic of Italian art as early as 1520. The technical brilliance of both pictures is memorable, most especially in the landscape glimpse of Toledo behind St. Martin.

Between 1596 and 1600 El Greco was busily engaged in preparing three large canvases for the high altar of the now-destroyed church of the Colegio de Dona Maria de Aragon in Madrid. The center of the altarpiece contained the Annunciation (Villanueva y Geltrú), the Adoration of the Shepherds (Bucharest), and the Baptism of Christ (Madrid). Here the supernatural atmosphere is maintained throughout, especially in the Annunciation, where the Madonna and Gabriel are enveloped in swirling clouds removed in time and place from all earthly experience.

El Greco's next major commission involved the altars (1603-1605) of the Hospital of Charity at Illescas in the province of Toledo, where litigation ensued and the trustees of the organization threatened to discharge him and engage a "good painter in the city of Madrid" at a time when El Greco was by far the greatest master in Spain. He finally agreed to accept a miserably inadequate payment, and there remains in the church today the celebrated picture St. Ildefonso, one of the artist's finest interpretations of an austere and ascetic saint.

El Greco's last major commission was for the high altar and lateral altars of the Hospital of St. John Extra Muros, unfinished at his death. The architectural design of the high altar was modified by the artist's son (1625-1628). In one fragment, the Fifth Seal of the Apocalypse (New York), El Greco reached the ultimate in the expression of the fantastic vision as described in the Book of Revelations.

El Greco produced numerous religious works dedicated to the Passion of Christ, such as Christ Carrying the Cross and the Crucifixion, as well as two series of the 12 Apostles (all Toledo). His votive pictures include St. Francis, St. Jerome, the Magdalen in Penitence, and St. Peter in Tears. Two famous landscapes survive: the stormy, romantic, and highly subjective View of Toledo (ca. 1595; New York) and the later topographic View and Plan of Toledo (ca. 1610; Toledo), so beautifully painted in thin grayish tones. In the center the artist placed the Hospital of St. John Extra Muros on a cloud so that it could be seen better, as he explains in the legend on the canvas. To these last years too belong his fantastic interpretation of Laocoön and His Sons, with the subjects being strangled by the serpents sent by Neptune—against another mirage of the city of Toledo.