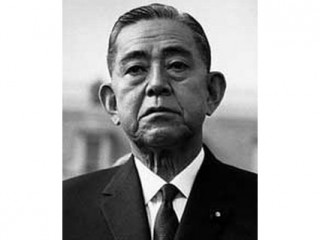

Eisaku Sato biography

Date of birth : 1901-03-27

Date of death : 1975-06-02

Birthplace : Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan

Nationality : Japanese

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-03-19

Credited as : Politician, foremer Prime minister of Japan, House of Representatives

Eisaku Sato was a Japanese political leader who served as prime minister longer than anyone else in Japanese history. Under his leadership Japan gradually began to translate its immense economic strength into enhanced political power in the international environment.

Eisaku Sato was born on March 27, 1901, in Yamaguchi Prefecture into a family of samurai descent. His home province, Choshu, provided much of the leadership (including Sato's great-grandfather) in the movement that overthrew the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868 and established the new imperial government. During the first century after the Meiji restoration, Yamaguchi provided more premiers than any other prefecture.

Sato therefore grew up in an atmosphere highly charged with political concerns; his mother was reported to have impressed upon her sons a sense of obligation to serve the state. Sato's eldest brother, Ichiro, became a rear admiral, retiring just prior to World War II. Another older brother, Nobusuke Kishi, served in the Hideki Tojo Cabinet as minister of commerce and industry during the war and subsequently, after serving 3 years in prison as a Class A war criminal, became a leader of the Liberal Democratic party and served as Japanese prime minister from 1957 to 1960.

Like Kishi, Sato attended Tokyo Imperial University, a ladder to success in Japanese society, and graduated in 1924 after studying German law. For a time he was interested in working for the N.Y.K. steamship line or the Ministry of Finance, but neither yielded him an opportunity, and he eventually ended up in the Transportation Ministry. His rise in the bureaucracy was not meteoric in the way Kishi's was in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Starting in a minor provincial post, he slowly rose through the ministerial hierarchy to become director of the Automobile Bureau. He was reportedly demoted after an argument with the deputy minister and sent to Osaka. The fact that he was not at ministerial headquarters saved him from the postwar purge.

Immediately after the war Sato was named general director of the Railway Administration and was soon promoted to deputy minister of transportation, the highest rank a civil servant could aspire to. At this juncture he made a decisive departure from his bureaucratic career.

The Occupation's purge of large numbers of the prewar political elite left room for new people to enter parliamentary politics. Shigeru Yoshida, the prime minister, was in the midst of building up a strong personal following in the Diet, composed mainly of former bureaucrats. One who came to his attention was Sato. It is said that Sato's handling of troublesome new labor unions caught the attention of Yoshida. However that may be, Yoshida asked Sato, in 1948, to become his chief Cabinet secretary, a position of considerable importance in running the affairs of the Cabinet and supervising relations with the party. Sato accepted and soon after won a seat in the Diet.

Sato's association with Yoshida lasted for several years, and he was intensely loyal to the old man. Yoshida suffered public criticism in the spring of 1954, when he rescued Sato from legal charges growing out of a scandal that involved shipping interests and many top leaders of Yoshida's Liberal party. Sato, who was serving as secretary general of the party, was accused of having received political bribes from shipbuilding executives. Yoshida employed the powers of his office to intervene and prevent the arrest of Sato, who thereafter always maintained his innocence.

In late 1954 Yoshida, whose position had been weakened by the scandal and more basically by increasing factionalism among the conservatives, was unseated by Ichiro Hatoyama. The following year Yoshida's Liberal party merged with Hatoyama's conservatives to form the Liberal-Democratic party. Behind the thin facade of party unity, factional strife continued unabated. Sato had by this time built up a strong personal following which he threw behind his brother Nobusuke Kishi, who with Sato's help became prime minister from 1957 to 1960. Sato entered the Cabinet as minister of finance. The immense popular disturbances that attended the Security Treaty crisis in 1960 toppled Kishi, who was succeeded by Hayato Ikeda.

Sato himself gradually built up his own claims to the premiership. Ikeda defeated him in a bitter struggle for the party presidency in 1964; but later in the year Ikeda, dying of cancer, was forced to retire, and Sato succeeded to the party presidency and the premiership by acclamation.

The crisis in the universities and continuing problems of Japanese-American relations were two of the major challenges confronting Sato during his term as prime minister. To deal with campus disorders, which wracked nearly all the universities in Japan, Sato's response was a bill that would allow the Ministry of Education to take over a school if the disruption persisted more than nine months. It was evident in elections that Sato's party benefited from a hard line on student disorders.

In November 1969 Sato flew to Washington seeking to conclude negotiations for the reversion of Okinawa to Japanese sovereignty by 1972. Upon returning to Japan, he dissolved the House of Representatives, and in the general elections held on December 27 his party won a resounding victory. In June 1971 the United States and Japan signed a treaty to restore Okinawa and the other Ryukyu Islands to Japanese sovereignty in 1972; the accord was ratified by both countries in March 1972. In July the 71-year-old premier resigned. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1974, along with Sean MacBride, for his policies on nuclear weapons that contributed to stability in the geographic area. He died the following year, on June 2, 1975, in Tokyo.