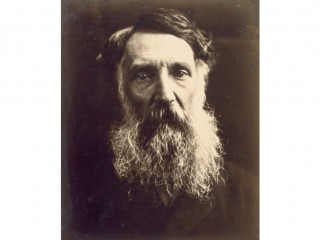

Edward John Eyre biography

Date of birth : 1833-03-20

Date of death : 1901-11-30

Birthplace : Hornsea, Yorkshire, England

Nationality : English

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2011-03-14

Credited as : Explorer of Australia, Mount Hopeless, West Indies administrator

Edward John Eyre was an English explorer of Australia and an administrator in New Zealand and the West Indies. He was tried for murder in the ruthless suppression of a Jamaican uprising and was acquitted.

Contrary to general belief, Edward John Eyre was born not at Hornsea, Yorkshire, but at Whipsnade in Bedfordshire on Aug. 5, 1815. His father was the Reverend Anthony Eyre, Vicar of Hornsea and Long Riston. Edward lived and was educated in Yorkshire. He completed his schooling at Sedbergh Grammar School and soon after decided to seek his fortune in the colony of New South Wales, where considerable opportunities were opened up by the expansion of the pastoral industry. Arriving at Sydney on March 20, 1833, he moved to the rich Hunter River district. In 1834 he acquired a property near Queanbeyan in New South Wales, but his stock were struck by disease. In January 1837 he returned to Sydney to start a fresh life driving sheep overland, first to Port Phillip and then even farther afield to Adelaide. There he established a home in 1838.

A young man of adventurous disposition who had become accustomed to the hardships of the bush, Eyre turned his attention to exploring. He undertook two expeditions to the north of Adelaide in 1839, and in 1840, at the invitation of a committee of Adelaide interests, prepared for an exploration of the Australian interior. Nothing was known of the central part of Australia, but there were rumors of an inland sea and of the existence of rich pastoral land, for which there was a strong demand. On June 18, 1840, Eyre set out with a small party of two aborigines and three white men, including his foreman and companion on previous trips, John Baxter, to clear up some of these mysteries. For over a month they journeyed in a northerly direction through hot, dry land, eventually turning back in despair at a point which Eyre sadly named Mount Hopeless.

To amend his failure, which weighed heavily on his mind, Eyre resolved to do what no one had previously accomplished, namely, to follow the coast westward around the Great Australian Bight and examine its practicability as a stock route. Despite initial setbacks and the attempts of friends and the governor of South Australia to dissuade him from this hazardous undertaking, he set out from Fowler's Bay on Feb. 25, 1841. Water was short, the terrain difficult, and the temperature extreme. Baxter was murdered by the natives, and only Eyre and a boy named Wylie completed the trip to Albany, a chance meeting with a French whaling ship at Rossiter Bay having provided much-needed assistance.

As an explorer, Eyre was noted more for his courage and perseverance than for finding anything of great value. He had failed to penetrate into the interior, and he discovered little that was not already suspected about the coastal country.

After returning to Adelaide, Eyre was made a magistrate and protector of the aborigines at Moorundie. In December 1844 he sailed for England and in 1846 was appointed lieutenant governor of New Zealand, where he served under and clashed with the governor, Sir George Grey. In 1853 Eyre returned to England and a year later sailed for the West Indies, where he served as lieutenant governor of St. Vincent, acting governor of the Leeward Islands, and governor of Jamaica. He suppressed a serious mutiny in October 1865 but he was recalled following the court-martial and hanging of a member of the local legislature who had been implicated in the uprising.

In England there was a public outcry in which leading figures like John Stuart Mill, Julian Huxley, and Herbert Spencer attacked Eyre, while others such as Thomas Carlyle, Alfred Lord Tennyson, and John Ruskin sprang to his support. Eyre was twice tried and acquitted, but it was not until 1874 that he was allowed to retire on a governor's pension. He died on Nov. 30, 1901, in Devonshire.