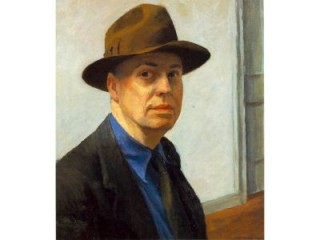

Edward Hopper biography

Date of birth : 1882-07-22

Date of death : 1967-05-15

Birthplace : Nyack, N.Y.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-03-10

Credited as : Realist painter, and printmaker,

A pioneer in picturing the 20th-century American scene, Edward Hopper was a realist whose portrayal of his native country was uncompromising, yet filled with deep emotional content.

Edward Hopper was born on July 22, 1882, in Nyack, N.Y. At 17 he entered a New York school for illustrators; then from 1900 he studied for about 6 years at the New York School of Art, mostly under Robert Henri, whose emphasis on contemporary life strongly influenced him. Between 1906 and 1910 Hopper made three long visits to Europe, spent mostly in France but also including travel to other countries. In Paris he worked on his own, painting outdoor city scenes, and drawing Parisian types. After 1910 he never went abroad again.

Back home, from about 1908 Hopper began painting aspects of the native scene that few others attempted. In contrast to most former Henri students, he was interested less in the human element than in the physical features of the American city and country. But his pictures were too honest to be popular; they were rejected regularly by academic juries and failed to sell. Until he was over 40 he supported himself by commercial art and illustration, which he loathed; but he found time in summers to paint.

In 1915 Hopper took up etching, and in the 60-odd plates produced in the next 8 years, especially between 1919 and 1923, he first expressed in a mature style what he felt about the American scene. His prints presented everyday aspects of America with utter truthfulness, fresh direct vision, and an undertone of intense feeling. They were his first works to be admitted to the big exhibitions, to win prizes, and to attract attention from critics. With this recognition he began in the early 1920s to paint more and with a new assurance, at first in oil, then in watercolor. Thenceforth the two mediums were equally important in his work.

The 1920s brought great changes in Hopper's private life. In 1924 he married the painter Josephine Verstille Nivison, who had also studied under Henri. The couple spent winters in New York, on the top floor of an old house on Washington Square where Hopper had lived since 1913. He was now able to give up commercial work, and they could spend whole summers in New England, particularly on the seacoast. In 1930 they built a house in South Truro on Cape Cod, where they lived almost half the year thenceforth, with occasional long automobile trips, including several to the Far West and Mexico. Both of them preferred a life of the utmost simplicity and frugality, devoted to painting and country living.

Hopper's subject matter can be divided into three main categories: the city, the small town, and the country. His city scenes were concerned not with the busy life of streets and crowds, but with the city itself as a physical organism, a huge complex of steel, stone, concrete, and glass. When one or two women do appear, they seem to embody the loneliness of so many city dwellers. Often his city interiors at night are seen through windows, from the standpoint of an outside spectator. Light plays an essential role: sunlight and shadow on the city's massive structures, and the varied night lights—streetlamps, store windows, lighted interiors. This interplay of lights of differing colors and intensities turns familiar scenes into pictorial dramas.

Hopper's portrayal of the American small town showed a full awareness of what to others might seem its ugly aspects: the stark New England houses and churches, the pretentious flamboyance of late-19th-century mansions, the unpainted tenements of run-down sections. But there was no overt satire; rather, a deep emotional attachment to his native environment in all its ugliness, banality, and beauty. It was his world; he accepted it, and in a basically affirmative spirit, built his art out of it. It was this combination of love and revealing truth that gave his portrait of contemporary America its depth and intensity.

In his landscapes Hopper broke with the academic idyllicism that focused on unspoiled nature and ignored the works of man. Those prominent features of the American landscape, the railroad and the automobile highway, were essential elements in his works. He liked the relation between the forms of nature and of manmade things—the straight lines of railway tracks; the sharp angles of farm buildings; the clean, functional shapes of lighthouses. Instead of impressionist softness, he liked to picture the clear air, strong sunlight, and high cool skies of the Northeast. His landscapes have a crystalline clarity and often a poignant sense of solitude and stillness.

Hopper's art owed much to his command of design. His paintings were never merely naturalistic renderings but consciously composed works of art. His design had certain marked characteristics. It was built largely on straight lines; the overall structure was usually horizontal, but the horizontals were countered by strong verticals, creating his typical angularity. His style showed no softening with the years; indeed, his later oils were even more uncompromising in their rectilinear construction and reveal interesting parallels with geometric abstraction.

After his breakthrough in the 1920s, Hopper received many honors and awards, and increasing admiration from both traditionalists and the avant-garde. He died in his Washington Square studio on May 15, 1967.