Edvard Munch biography

Date of birth : 1863-12-12

Date of death : 1944-01-23

Birthplace : Loten, Norway

Nationality : Norwegian

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-07-19

Credited as : Symbolist painter, printmaker, best-known composition was The Scream

0 votes so far

Rather fortunately for Norwegian painter and printmaker Edvard Munch, he found expression for his bouts of physical and spiritual turmoil in his art, and during his lifetime enjoyed an estimable reputation with many critics and collectors; he also was an eminent figure to a generation of younger European artists and lent a profound impact to the direction of their work. He is widely considered Scandinavia's most famous and influential visual artist. But to the general public and those who did not know him personally, Munch was assumed to be mentally unstable. "My art is rooted in a single reflection," Munch once declared, according to Michael Gibson's 1997 book Symbolism. "Why am I not as others are? Why was there a curse on my cradle? Why did I come into the world without any choice?" Munch further noted that "my art gives meaning to my life."

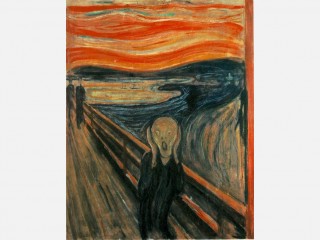

Munch's personal and professional career were marked by controversy, and almost all of his work before 1909 is infused with despair--he painted not the sunny landscapes of Claude Monet's Giverny, nor even the fields of humming wildflowers depicted by a certifiably unsound Vincent Van Gogh--both artists whose work a young Munch looked toward for technical and thematic inspiration. Instead Munch painted images of sickness, death, jealousy, and sexual dread, and it is a single painting that stands as a marker of his enduring power. It was also a work that caused many to assume that anyone who could imagine, then depict, such a scene of psychic terror must surely be himself deranged: 1893's The Scream. Since the day it was first shown in public, The Scream has become one of the most ubiquitous images of modern art and popular culture.

Munch was born on December 12, 1863, in Loten, a suburb of Oslo, Norway's major city that was then known as Christiania (the name was changed to Kristiania in 1877, and finally to its present name in 1925). He was one of five children of Christian Munch, a military physician and a deeply religious man. The elder Munch was the descendant of a well-known painter, Jacob Munch (1776-1839), and brother to a distinguished historian; the family also boasted a long line of academics and even clergy. Still, Munch came to feel that he had inherited his forebears' susceptibility toward both consumption, also known as tuberculosis, and mental illness. His mother, Laura, died from the deadly respiratory disease when he was just five, and a fifteen-year-old sister later succumbed to it when he was in his early teens. Another sister suffered from mental problems early in her childhood.

Munch himself was sickly as a child, often ill with bronchitis, and feared death was imminent for him as well. Even the fact that his father was a doctor brought him little comfort. Poverty and close living quarters played a role in the spread of tuberculosis, and the Munch family were poor despite their reputable name, living in tenement apartments outside the city. It was a household rife with tension and guilt. The death of Laura Munch plunged his father into periods of depression and only increased his religious fervor. Dr. Munch, plagued by occasional hallucinations and a violent temper, saw the deaths in his family as a punishment from God.

Artistic Talent Emerges

Early in adolescence, Munch became interested in art and began to display a talent for it. Not surprisingly, his father initially tried to discourage him from pursuing it as a career, and for a time Munch acquiesced to his wishes and took engineering courses in school. Finally he was allowed to enroll at the Royal School of Drawing in Kristiania around 1880, where he was able to meet and learn from other young people in the city who shared his interests and ideas. For a time he studied under Christian Krohg, then one of the most esteemed painters in Norway.

As he entered his twenties, Munch yearned to see the capital of European culture and wellspring of the avant-garde: Paris. In 1885 he arrived there on funds from a government grant and began painting landscapes. One recurring subject, which would hold an important thematic interest for Munch for most of his life, was the Norway resort Aasgaardstrand. In particular he loved its long Arctic summer nights and the special, almost eerie light these warmer months brought to its sky.

Munch took his canvases back to Norway and began exhibiting in the annual autumn salons in Kristiania. One of his earliest efforts from this period, which he had begun in Paris, was The Sick Child, a work commemorating the death of his sister. He showed this emotionally searing work, with its somber blue, green, and gray tones capturing a tragic interior scene of a woman bent in grief over a bedridden child, in the 1886 Exhibition, and was vilified by critics for it. "Most of my later work had its origin in this picture," Munch later said, typically undaunted by criticism.

In Kristiania, Munch moved in its more bohemian circles and counted radical anarchists and free-love enthusiasts among his friends. He also began writing, feeling the need to express in words what it was he was attempting to formulate in his art. After 1889, he began spending more time away from Kristiania. He went back to Paris, studied under Leon Bonnat for a spell, and there learned that his father had died. His 1890 painting Night is emblematic of the sadness and loneliness he felt upon receiving this news so far from home. A figure stands alone at a window, bathed in shades of blue.

Though Munch's art was infused with a particularly dour Scandinavian mysticism--pagan traditions thrived in these northern lands until the establishment of Christianity in Sweden around the ninth century, and in Norway two centuries later--his works were also indebted to Van Gogh and the French painter Paul Gauguin, both of whom employed vibrant colors and gave great emphasis to pattern and line. Gauguin was closely associated with Synthetism, a movement then thriving in France whose hallmarks were the use of intense shades of paint upon simplified, curvilinear forms.

Synthetism grew out of the French Symbolism of the 1870s and 1880s, and much of this new direction was a backlash of sorts resulting from the invention of the camera--a magical and much heralded innovation of the day. Munch once famously offered his opinion of the argument then raging between the opposing philosophical adherents of photography versus painting: "The camera will never compete with the brush and the palette," Munch wrote, "until such time as photographs can be taken in Heaven or Hell."

Disturbing, Disquieting Work

Many of Munch's most disturbing yet significant works emerged from his studio during the 1890s. These include Melancholy, sometimes called The Yellow Boat or Jealousy, which shows human figures against bleak landscape at Aasgaardstrand; a man in the foreground--probably Munch's art-critic friend Jappe Nilssen--cannot conceal despair as a woman and a man depart on a boat in the distance behind him. The ominous rocks and oppressive sky were Munch's way of using the physical world to echo the human soul's agony. It was first exhibited in the Autumn Exhibition of 1891 in Kristiania.

In 1892 Munch went to Berlin after an invitation by the Verein Berliner Kuenstler (Association of Berlin Artists) to mount a retrospective of his work there. The public was outraged at many of the works--Vampire was considered especially lurid--and it closed after just a few days. Because of the sensation, the Verein members voted on whether to shut it down, and the older, more conservative artists held the majority. The younger dissenting ones then broke with the Verein to launch the Neue Berlin Sezession (New Berlin Secession) movement, a stylistic and interpretative direction that became integral to the establishment of German Expressionism.

Yet the Berlin show and its attendant publicity helped boost Munch's reputation in Germany even more. He remained there for the next few years, and came to know Swedish dramatist August Strindberg, also in temporary artistic exile. Strindberg's bleak plays were characterized by tense interpersonal relationships, in many ways the stage equivalent of Munch's art. Munch later came to know another well-known Scandinavian dramatist and fellow Norwegian, Henrik Ibsen, and designed the sets for a staging of Ibsen's Peer Gynt in Paris. His contemporaries began calling Munch's work "psychological realism," a term used by Polish poet Stanislaw Przybyszewski in the book Das Werk des Edvard Munch, co-authored with German art historian Julius Meier-Graefe and published in Berlin in 1894. These two, plus Munch and Strindberg, established a convivial social set of intellectuals and artists who made a Berlin bierkeller called Zum schwarzen Ferkel their meeting place.

Munch began working more in the graphic arts around this time, but continued to work towards completing a cycle of paintings he called the Frieze of Life: A Poem about Life, Love, and Death. The first of the works in the series--which included the aforementioned Melancholy--were exhibited at a space on Unter den Linden, the fashionable Berlin avenue, in December of 1893. Death in the Sickroom (1893), another work commemorating the death of his older sister, was included. The following year Anxiety, Ashes, and the controversial Madonna, a nude in ecstasy, also joined the cycle.

The Scream

The Scream, sometimes called The Cry, also emerged from this fruitful period of Munch's career. It has been termed the work that sired German Expressionism, for it was one of the first to impact upon the viewer not the traditional artistic depiction of a specific moment in time or space, but rather a state of mind. Its expression of inner angst also reflected the late nineteenth century's increasing concern with the self and the burgeoning field of psychiatry. In the painting, a skeletal figure standing on a bridge covers its ears while the mouth is agape in an agonizing scream, a sound that does not appear to disturb in the slightest the two people in the background who are walking away. The screaming figure is in the foreground of the picture, but appears rushing toward viewer, increasing the feeling of anxiety. Surrounding this Munch painted ominous fjord and sky in thick, undulating blue-black tones and the red of blood. The tempera version of The Scream dates from 1893, but he also did a lithograph of it 1895. When first exhibited, it was disparaged by some as the work of an unsound mind. Munch himself wrote on its frame: "Could only have been painted by a madman."

Munch showed the completed Frieze of Life for the first time in its entirety in the Berlin Secession show of 1902. From this moment onward, Munch came to be a great influence upon some German artists working in Dresden around the years 1905 to 1908 who called themselves "Die Bruecke," or "The Bridge"; Emil Nolde was among them. Later, a few headed south to Munich and came to be known as the "Der Blaue Reiter" ("The Blue Rider") group, among them Wassily Kandinsky and Max Beckmann, and their works are considered the most faultless and dramatic images of pre-World War I German Expressionism.

Until about 1908 Munch alternated his time between Paris and Berlin, though he spent summers in Aasgaardstrand after he bought a small place there in 1897. Yet he had become embroiled in a desperate love affair--with incidents of blackmail and threats of suicide--that finally ended in Aasgaardstrand in a crisis involving a gun. The artist permanently damaged a finger trying to wrest the weapon away from his paramour, a woman who probably appears in his 1907 work Death of Marat. He had also begun to drink and smoke quite heavily, and from a combination of these factors he suffered a nervous collapse in 1908. He returned to Scandinavia, first to Denmark and eight months in a Copenhagen sanitarium, where he occupied his days by sketching the doctors and nurses. Later he returned to the Oslo area, and would remain in his homeland for the rest of his life.

Earns Honors

Oddly enough, Munch recovered relatively quickly from his breakdown and entered into a period of psychic peace and artistic renewal. (He would later say that he simply abandoned his twin vices of women and alcohol.) Settling near Oslo on the coast, he set up an outdoor studio for the warm months and from this point onward painted more pleasant, far less morbid scenes in gentle, subdued tones. He also took up portraiture in earnest, executing full- or three-quarter-length works depicting his friends and some of the best known names of the era, such as his portrait of the philosopher Frederic Nietzsche (1908). Munch was knighted with his country's Order of St. Olav in 1908, and the following year its Nasjonalgalleriet in Oslo began purchasing his work in earnest for their collection. At the time, the curators' first 1909 acquisition was the museum's largest purchase in its history of work by a living artist. He also won a large commission for murals that decorate the Aula of the University of Oslo, which he worked on from 1910 to 1916. There was some controversy about installing them, but those at the college who recognized Munch's status won out, and they were put in place and he was paid. With the proceeds he bought a place in Ekely, also near Oslo.

In 1912 Munch was feted at the Sonderbund Internationale Exhibition in Cologne, Germany, which placed his works in the realm of all the pioneers of modern art. He and Pablo Picasso were the only two living artists given their own gallery rooms. Munch became interested in the burgeoning trade union movement in Scandinavia, and painted Workers on Their Way Home (1913-15) as a reflection of this liberal bent. During the 1920s, he was honored with numerous exhibitions throughout Europe, and in 1933 he was bestowed with the Grand Cross of St. Olav in honor of his seventieth birthday. That same year the first of several biographies of Munch appeared in print. But seven years later Norway was occupied by Nazi Germany, and Munch lived out his final years in Ekely under foreign rule. His works that were in German and Norwegian museums were condemned, along with the art of the German Expressionists, as "degenerate" by the German chancellor Adolf Hitler and removed from public view. During the winter of 1943-44, an explosion at a nearby munitions factory shattered the windows of Munch's house. As a result he became gravely ill, and died in January of 1944 at the age of eighty.

Munch's will bequeathed all of the works in his estate to city of Oslo, and over the next few decades curators worked to acquire other paintings by the artist that had been sold to private collectors through his dealers during his lifetime. Finally in 1963 his legacy was formally christened with the opening of the Munch Museet in Oslo. The Nasjonalgalleriet is home to the remainder of Munch's work in Norway.

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Born December 12, 1863, in Loten, Norway; died January 23, 1944, in Oslo, Norway; son of Laura Catherine (Bjolstad) and Christian Munch (a military doctor). Education: Attended Royal School of Drawing; studied under Christian Krohg; studied with Leon Bonnat in Paris, c. 1889.

AWARDS

Awarded Order of St. Olav, 1908, government of Norway, and the Grand Cross of St. Olav, 1933.

CAREER

Painter, living and working primarily in Paris, France, and Berlin, Germany, from 1889 to 1908, and near Oslo, Norway, after 1908. First traveled to Paris, 1885; mounted first solo show of his own work in Kristiania (now Oslo), 1889; settled in Berlin, 1890; show at the Verein Berliner Kuenstler (Association of Berlin Artists) in 1892 closed by scandal; work included in the Armory Show, New York City, 1913; awarded commission for murals of the Aula of the University of Oslo, 1910. Exhibitions: Major collections of Munch's work are housed in two museums in Oslo, Norway, the National Gallery, and the Munch Museum. The artist exhibited at the annual Autumn Exhibitions in Kristiania, Norway, during the 1890s, and was invited to participate in the Sonderbund Internationale, Cologne, Germany, in 1912, and in the Berlin Autumn Exhibition, 1913. Many European museums hosted retrospectives of his work beginning in the 1920s, and continuing after his death well toward the end of the century on an international spectrum.