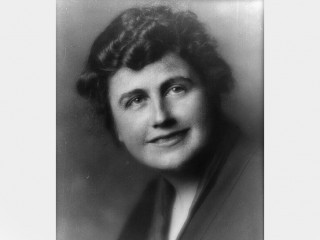

Edith Bolling Wilson biography

Date of birth : 1872-10-15

Date of death : 1961-12-28

Birthplace : Virginia, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-08-05

Credited as : First lady of the United States, wife of President Woodrow Wilson,

0 votes so far

While visiting her sister Gertrude in 1889, Bolling met Norman Galt. After a long courtship they were married in 1896. Several years later Norman Galt became chief owner of his family's jewelry and furnishings business.

In 1908, Norman Galt died, leaving his wife wealthy. With the aid of employees she ran the jewelry business with the proverbial iron hand in the velvet glove. She traveled annually to Europe, often in the company of Alice Gertrude Gordon. In 1915, Gordon was being courted by Dr. Cary Grayson, personal physician to President Woodrow Wilson, whose first wife, Ellen Axson Wilson, had died the previous August. Through Grayson and Gordon, Wilson and Galt met in March 1915. A whirlwind courtship ensued: Wilson's love letters are among the most eloquent in American presidential history. The relationship disturbed Wilson's advisers, including his friend Colonel Edward M. House. Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo, who was married to one of Wilson's daughters, even used anonymous disparaging letters to attempt to keep the president from marrying Galt so soon after his bereavement. But Wilson appreciated Galt's wit, warmth, and charm. Rejecting all counsel, he and Edith Galt were married on Dec. 18, 1915.

Edith Wilson became one of her husband's most trusted advisers, having access to secret cables and important state papers. In general she acted as a sounding board. They were seldom apart more than a few hours each day. Although the second-marriage issue proved inconsequential, the 1916 election campaign was one of the dirtiest on record, and Edith Wilson suffered from many personal slurs.

When the United States declared war against Germany in 1917, Edith Wilson took a leading role in persuading American women to conserve resources. But she believed her most important task was to care for Wilson and help him to relax. In November 1918, when the armistice was declared, she was one of the few advisers who urged the president to go to Paris to negotiate the peace treaty personally. Wilson's brief illness in Paris during the spring of 1919 increased her role, as she tried to keep the president from exhausting himself. Colonel House felt her influence then to be pernicious, a factor in his break with the president. Later scholarship has disputed this contention.

After Wilson suffered a paralyzing stroke in the fall of 1919, Edith, convinced that he would soon recover and not wishing the government to be taken over by persons hostile to the Versailles Treaty and the League of Nations, acted as a shield for the president. With the backing of Dr. Grayson, she allowed no one to enter his sickroom or to communicate with him, either on paper or in person, without her consent and, most often, her presence. For several months in late 1919, Edith Wilson took her husband's dictation, relayed his wishes to Cabinet members and other officials, and gave him the latest news.

At the time, and in the years immediately following her husband's death, Edith Wilson was castigated for her role during his illness. It was charged that she was usurping the authority of the presidency. Later evidence, though, shows that she made no policy decisions by herself. But by exercising the power to keep in and keep out, she did affect the workings of the government, in the way that any powerful adviser affects a president's decisions. Wilson's recovery in 1920 was slow and incomplete, but he managed to complete his term. Edith helped dissuade him from attempting to run for a third term. Her counsel was also a major factor in Wilson's refusal to endorse his son-in-law William McAdoo for the nomination.

After leaving the White House in 1921, the Wilsons resided in Washington, and Edith Wilson continued to care for her husband until his death in 1924; thereafter she guarded his papers and historical image with equal zeal. In her later years she kept up her friendships with Herbert Hoover, Bernard Baruch, the Franklin Roosevelts, and others at the center of power. She was an indefatigable world traveler and a mainstay of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation.

That she did not abuse her temporary stewardship in 1919 is a judgment that is only slowly replacing the popular idea that Edith Wilson was the real president at that time. It is incontestable, though, that during the fall and early winter of 1919, she held more power in her hands than any other American woman before or since.